Anatomy of a Buzz

The Making of Asamov

Shelton Hull

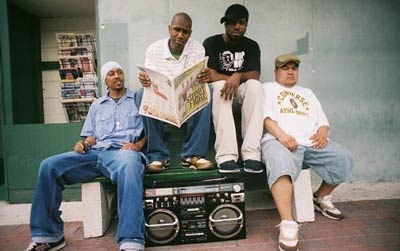

“Summoning the pass-the-mic group ethic of rap music’s past, this Jacksonville-based quartet achieves a feel-good vibe on its debut via soulful beats, vocal harmonies, and doses of humor.” These 31 words, from the “Indie Beat” section of Vibe magazine’s December 2005 issue, marked the formal arrival of Asamov as a national act. While their work in that realm has barely started, the events of 2005 have taken them further than any other area rappers have gone in recent memory.

Theirs was a process of incremental progress, with no shortage of uncertainly along the way, but each step has provided some valuable lessons to newer artists wishing to find themselves in similar positions down the line. So, while the group was resting up for the even-more hectic year to come, the details of that process were obtained. It turns out that the easiest part of making a name in the music business is the music itself, while the nuances of industry practice and protocol can be a minefield for rookies.

Asamov was formed in 2001. “Basic and J-One-Da, at the time I was living with them, so we were always working on songs together. Therapy was coming around and doing joints with us. ‘Asamov’ started out as a crew name; when Desi stepped to us, that’s when we sat down and really solidified it as a group.” Their name refers to author Isaac Asimov, but intentionally mis-spelled– or, “re-spelled”– in recognition that his legacy is secure, whereas theirs is not. “We’d like to bring the same to the table” in regard to music, says Willie Evans, Jr. as Asimov did in the field of science-fiction writing.

6Hole Records was started by Desi Relaford, a 14-year veteran of Major League Baseball who once played for the Jacksonville Suns. The name is a reference to his usual position at third base (not to be confused with 3rd Bass). He approached Therapy (an old friend) and Evans about working together. “We played him the batch of songs we were working on,” says Evans, “and he got amped on it, and it started from there.”

A brand-new label and a brand-new band. It could have been a recipe for disaster, but it’s worked out to the general satisfaction of all involved. Maybe that’s just spin, but these are not wallflowers. There’s no performance anxiety, no nerves, no fear of speaking out. One thing about rappers: they will never hesitate to answer a question.

“At the time when he started the label, it was just him, and us feeding him ideas. None of us had any idea what a label was supposed to do to get music out. As time went on, he started picking up people on the team,” including the Boston-based PR firm Metro Concepts, which assisted in running the business while Relaford was on the road during the baseball season. “There have been a lot of growing pains, but I think that process really helped Asamov to develop the sound to where it is now.”

Going further, Evans notes that Relaford’s involvement was crucial to the entire enterprise: “Make no mistake, without Desi, there was absolutely no way that Asamov would be at the point we’re at right now. We may have still gotten on another label and gotten music out there, but it wouldn’t have been under our conditions. We would almost certainly have had to leave Florida to get on a label that was going to put us out.”

Support of that kind is essential, but the members of Asamov are a solid, efficient core around which to build. Each man brings specific skills to the table, in terms of both art and business. Their arrangement works so smoothly, says Marley, that “If we’re all together, it’s probably for a show,” but news travels fast. Basic DJs, MCs, oversees the online activity, which keeps him in regular contact with the group’s core fans. “Of the four of us, his name is the most accurate description,” says Evans with a twinkle. “He grounds us. J-One-Da brings a lot of newness to our sound.” He is probably the best salesman of physical product because of height and ability to talk through background noise.

Therapy’s widespread DJ work has led to establishing primary contacts with many key associates. “He brings the rawness of being himself. As an MC, he’s the total package.” Evans’ Underground Utilities was the last five-star record of the 20th century, and a harbinger of trends to come in the industry.

“Blow Your Whistle” was the group’s first release. LPs were cut on clear red vinyl, while CDs came packaged with clear red whistles that some fans still take to shows years later, as seen in the Endo Exo footage. The song “was one that Therapy and J-One-Da had done; the B-side was ‘Don’t Stop,’ which was a song with me and Basic. It was the strongest one to take our first step forward with.” (Another song from that initial batch was the instant classic “Bizarre.”)

Asamov’s manager, Damian “D-Diddy” Marley, joined the team almost by accident a year ago after watching them perform at Red Rock’s mixtape release party. “The first thing I discussed with 6Hole was consulting/A&R, but it didn’t take long to realize that you can’t put too much distance between label stuff and what Asamov had [to do].”

After speaking with Relaford and members of the group, “it just progressed to working with them and getting deeply involved with them, because I saw the potential. Asamov has always been one of the top two or three independent situations I’ve seen. If you want somebody to come in and manage, you’ve got to have something to manage. If you’ve got a bunch of demos, a bunch of smatterings of a project, keep working on it and maybe six months, a year from now you might have something that’s a situation.”

“After six months, it’s been a big wake-up call,” says Marley. “The nature of the music industry is such that even the big dudes aren’t blowing up. A lot of people I know in the industry are trying break even off their projects; if they are making a little money, it’s off the back end, [from] stuff like licensing and publishing.”

The CD listening party at Burrito Gallery on October 15 was Asamov’s last gathering before officially becoming a national act three days later. Members of the group spent much of the night running around in their own sub-orbits, giving out promotional items like the Otis Hodem mixtape and mingling with people.

A modest man with skills to spare, Willie Evans, Jr. may be the most well-liked MC in town. Ignoring, briefly, the request from a patron to buy a round, Willie Evans, Jr. notes how “extremely fortunate” he feels to be “living a dream.” He admits to being nervous about the release, but added sagely that “it’s really more about six months after the release,” rather than first-week sales alone.

To pull monster first-week sales is very hard to achieve, even under ideal conditions. Only a handful of rap labels and just a couple dozen artists can generate the kind of pervasive buzz that leads to such sales, having built up enough “sweat equity” through consistent sales to justify the expense of a major push. An act that is signed to a major label but is not being actively promoted often ends up buried in the mix. The rap industry, in particular, is notorious for keeping people’s albums on the shelf for years, which can be ruinous in a style that is an expression of their present-day reality– from speech patterns to the references in the lyrics and beats.

A “major” label can be defined in several ways. It can be located anywhere, but it must have some kind of New York presence, because it’s the nexus of global media and a preeminent repository of talent in most artistic fields. LA, Chicago, Philadelphia, Detroit, San Francisco, Atlanta and Miami are all places a major label would have at least one full-time representative. Like magazines or banks, no amount of money can build the infrastructure for a self-sustaining label overnight.

The music industry is a sucker bet above a certain scale, as the market is moving more toward digital media and other, less fungible product. “We’re caught between the changing of the guard,” says Marley. 6Hole has plenty of upside, but cannot spend on a level that will get them on Clear Channel or MTV, so their strategy is to push quality over quantity. It is a sound approach, according to former Village Voice staffer Kem Poston, who’s covered urban music and related issues in three of the five top media markets. “Independent labels,” he says, “are a viable option for legit artists that don’t conform to major label standards.”

The northeast, New York in particular, has always been a bit reluctant to embrace talent from outside their sphere because hip-hop was born in the Bronx and had worked its way into all five boroughs before anyone outside New York was conscious of it. The New York scene was the rap business for almost a decade, from Sugar Hill to Def Jam to Tommy Boy, before losing substantial market share to operations out of Florida, Texas and, most convulsively, California. The latter was notably acrimonious, setting in motion a wave of violence and recrimination that might have resulted in Congressional hearings, had the Republican Congress of the mid-‘90s not been preoccupied with Impeachment.

Regardless of what happened to Biggie and Tupac, their deaths put many people in bad moods that lingered in the music and left mainstream audiences with a distinct concept of the industry that led to increased scrutiny of lyrical content. The mainstream media– which prior to 1996 displayed a pervasive ineptitude in covering the music– developed a taste for “beef” and the rappers gave it to them. The dark years had a chilling effect, even as hip-hop had unprecedented commercial and cultural success.

New York has reclaimed its place atop the US hip-hop market, in part by opening the industry up to “outsider” acts like never before. 2006 may see Def Jam (“the General Motors of rap”) out with an 18-year-old British girl as the pump is being primed for new MCs to emerge on other labels from Japan, Russia and Israel. Domestically, top earners in the business include people from Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Michigan and Virginia, besides California and New York. The extent to which this new egalitarianism resulted from deliberate action or “market forces” is unknown.

Geography aside, newer groups like Asamov must prepare for the possibility that “underground” hip-hop, at one point the freshest of fresh ideals, could be rendered a cliché just as the pragmatic thug motif was overexposed in recent years. “Much of underground Hip Hop is played out and is playing itself out because it’s lost or stuck in its own inferiority complex,” says Brent Mock of Pittsburgh’s City Paper. As he tells it, “The problem with groups like Little Brother, Blackalicious, Jurassic Five is that they’re all stuck in a Jurassic age of Hip Hop, and their nostalgic wax is as tired to listen to as mainstream artists talking about ice grills and fancy cognacs. In fact, lately I’ve found the artists who rap about diamond and platinum teeth more interesting than the artists who gripe about the artists who rap about diamond and platinum teeth.”

“Asamov is going to rep Florida in a way no one has before,” said Mr. Lif, a noted part of the Def Jux stable. He did not know the reporter was from Jacksonville or had ever heard of Asamov. He was on the road somewhere in the northeast, and DJ Therapy was in the car with him– a pleasant enough surprise.

Therapy joined the tour after Perceptionists’ DJ Fakts One became a new father some weeks prior, and he remained in the booth for almost the entire tour, including key segments with both groups. The Asamov/Perceptionists connection goes even deeper: Evans produced three tracks on their Black Dialogue album (released March 25), including the title track; he also has several tracks in the can for Lif’s forthcoming solo album. Therapy is from Boston, and both groups use Metro Concepts.

Asamov’s inaugural tour began with five weeks up the west coast. After a break for the CD release, they did two more weeks starting in late-October. By the time they returned to Jacksonville to wrap up the tour on November 17, all the CDs and t-shirts had been sold, but for some 6Hole ball-caps and a few copies of the mixtapes. More supplies arrived later, but they did not last through the night. Ryan, a 28 year-old landscape artist, bought his copy of And Now at that show; within 48 hours, he’d already listened to it approximately 17 times. “It hasn’t left my CD player since I got it,” he says, “all day long at work, and work is a ten-hour day. I’m just guessing.”

In a previous era, label executives might not have wished to see their artists so openly collaborating with other acts, thinking that such work would dilute the potential revenue stream for the label. In fact, it creates more possibilities for business by exposing the artists to new listeners, creating a positive feedback loop that expands the audience for both acts. This has proven a fundamental in the current leaders of hip-hop, bringing it closer to the jazz scene of the 1940s and ’50s and the dub scene of the ’50s and ’60s; both genres made spectacular returns on certain investments.

Holding a copy of And Now, Marley points to a black sticker on the front with the names of featured guest MCs on it. “I know we sell more records because of this sticker,” he says. “What other records came out with Lif, Ak, 9th Wonder on it, J-Live, in the last 12 months?” He notes the value of “co-signing,” which is when an established artist lends credibility to a newer talent by appearing on their recording or bringing them along on tour. “The thing that greases the music industry is favors getting done for people.”

“Asamov taught me that you need stage presence, period,” says Tough Junkie of Simple Complexity, which has sold over 1,500 CDs and garnered good looks using many of the same techniques that Asamov helped perfect over the past decade. “If you don’t have stage presence, your shows will not be good and you will not sell anything. Nobody will believe in your music if you can’t show them that you believe in it.” Evans agrees: “At the end of the day, nothing beats human interaction.”

Touring exposed Asamov to key parts of the hip-hop nation, and vice versa. “The ‘hip-hop scene,’ collectively, is a collection of small scenes,” says Evans. “From what I’m seeing, it fluctuates between maybe 200 and 2,000. Obviously places like New York and Cali are really exceptions to that. The Bay area’s amazing!” He adds that he sees that region as a model for what can happen in the Southeast in the near future.

And Now was released on October 18. All copies shipped to Jacksonville sold out that day. Sales were brisk elsewhere, but with larger quantities shipped a similar outcome did not materialize. Asamov’s reps claim sales are well-ahead of projections, but there is no way to know exactly how many CDs have sold. This works in the group’s favor, since SoundScan’s numbers are generally accepted as being highly inexact.

The album’s first single was “Supa Dynamite” (featuring Mr. Lif), a particularly strong track that holds up with some of Asamov’s most well-known songs. Like “Blow Your Whistle,” it’s the best foot to put forward. The song might sound valedictory, or even slightly wistful, perhaps because Asamov’s national debut is a marker between phases in the broader history of music in northeast Florida. As a single, it fared well on the underground charts, peaking at #3 on Record Breakers and #2 on Rap Attack.

Critical response has been strong: Four-star reviews by HipHopSite.com and Okay Player and positive mention in Vibe, Urb and Billboard (which called the album “strong and coherent”); articles in Axis, Orlando Weekly and the Florida Times-Union. They were selected for inclusion on promos released by Spitkicker and Preemptive Hype; Resonated Radio sponsored a “Hookslide” remix contest. Even better than all the good reviews is that they got no bad ones. If, say, Vibe had used the space to dis the album, or worse, to dismiss the act with the same brevity it used in recommending them, the results would have been catastrophic. A single well-written, highly-placed bad review can tank any momentum an artist has built up.

SoundScan has reportedly entered about 4,000 copies into their system. It is unclear how many of those were sold, or even if it matters all that much to the team. “Websites don’t SoundScan. Mom and Pop don’t SoundScan,” says Marley. Neither does iTunes, which has sold hundreds of albums and singles. At the end of the day, raw numbers mean less to Asamov than the reach of their material and the group’s long-term momentum. “The project is an investment on 6Hole’s catalogue and the second record of Asamov’s career. Not to take the focus off the first one, but we got the record put out as our ticket being punched in the industry, and people are still picking up on us.”

A potent weapon in Asamov’s promotional arsenal has been MySpace.com, a site that should be familiar to most readers by now. With over 40 million users, it has emerged as perhaps the last great success story of the dot-com boom. Conversely, it may also be the first great success story of the nanotech revolution, in the sense of having simplified the act of establishing an Internet presence accessible to all users. Asamov’s page on the site has been visited over 30,000 times, and the evidence suggests that the vast majority of those viewers were from outside their home base.

Jason Braddock has seen the effect from multiple angles. “I’ve heard 20 to 30 bands I never would have heard of, just by seeing something listed somewhere from another friend’s page,” says Braddock, 29, a graphic designer who plays in the band Schwaray and helps organize local bands in his remaining time. He estimates that “three or four hundred” local bands have spots on MySpace.com, ranging from “some people who barely even play out, they just do something out of their bedroom, to bands that play three to four times a week. You’ve got bands like Ariel Tribe, who play all over town, who put on amazing shows, who have a great EP and a great full-length. And then people like Chase Capo, who comes up and plays banjo, from out of nowhere, and talks a little politics, or Joel Land, who does comedy.”

Asamov is among the first groups who can plausibly claim that the website played a significant role in their emergence as a national act, and vice versa. With nearly 5,000 “MySpace Friends” who themselves have hundreds or thousands of friends each, when Asamov posts a bulletin to each of the group’s nearly 5,000 friends, and each of them reposts the bulletin to all of their friends, the bulletin will reach several million people’s computers in minutes– faster than any promotional method yet devised. Although some interesting things are happening now in wireless media, usage of these devices is small, compared to the proliferation of PCs and laptops around the world.

The concentration of youth in Florida results in part from the state’s university system, which is one of the best in America. There is also the longstanding military presence and the climate, as well as the crucial cultural draws to the south: St. Augustine, Orlando, Miami and the Keys, most notably. That Florida has an inordinate number of people who use MySpace is a fact recognized by the company, which invited them to perform as part of the MySpace Florida Invasion Tour at Orlando’s Metropolis on December 9. Evans called the show (which included Rob Roy, X:144 and DJ SPS) “an excellent microcosm” of the site itself. “It was the illest collection of people I’ve ever seen in one place.” Asamov was also featured on the site’s front-page alongside Beck and Lil’ Wayne, which provided exposure to over 2 million more daily.

Asamov’s style of music works effectively with the technology. The music is built around loops, drum patterns and voices, so it loads fast even on slower computers and plays with more fidelity than, for example, symphonic music; these are factors that enhance the music’s marketability via the medium. The group has so many tracks done already that it allows them to rotate “classics” with new material online.

The CD release party had been scheduled for October 17, but was switched to Endo Exo on the 23rd after a dispute over an Asamov mural that had been commissioned by local artists for the side of London Bridge. The mural covered an older piece depicting a Royal Palace Guard (ironically, by the same artist) that was beloved by someone who had the new piece whitewashed in response. The mural was “a huge success,” says Marley. “It’s almost better that it didn’t stay up that long.”

The weather was cooperative, but the threat of rain kept a surprising number of people away. The club spread a blue tarpaulin across the framework of the outside patio, just in case. A white guy wearing an Artis Gilmore #53 jersey intrepidly stalked the stage shooting the show. It was the first time X:144 had performed in Jacksonville. He and DJ SPS (no stranger to the city) would also represent Orlando and Nonsense Records at the November 17 and December 9 shows; their live act is second to few.

DJ Shotgun of P.I.M.P. Organization held the turntables in place for Asamov’s set. His Getting’ To Know Us Mixtape aka “The Return of Otis Holdem” has proven a key part of their catalogue. It was a limited-edition CD of remixes and older material from the Blow Your Whistle and Trailer Park EPs. It ends with “Hookslide,” “Boombox” and “Supa Dynamite” from the album. The CD was included with pre-orders of And Now through HipHopSite.com and distributed prior to the album’s release. Thus, anyone who has the album and wants more Asamov will seek out an already-scarce product.

Evans estimates the group has recorded at least 40 tracks in four-plus years, but it’s impossible to get an exact figure. It is also impossible to get exact sales figures for And Now, due to the vagaries of the music business. There are many reasons why casual observers are discouraged from obtaining such information, but the bottom line is that there’s no cost-effective way to even track domestic sales figures, much less globally.

Asamov’s future is grounded in its past and a realistic view of the present. For Evans, the hardest part of the process has “having one foot in and one foot out. We have a nationally released album, and three of four of us still have [9-to-5] jobs. Until the release, I had two. … What they say is true: The positive response to the album does not translate to being able to immediately pay all your bills, especially on the first album. I’d read a lot of books that said the average artist ends up owing money when they get ready to record their second album.” This will not be the case for Asamov, which enjoys the complete support of a label that needs them to succeed for it to succeed.

“I was imagining that in the independent realm it would be sort of a different story, and for some artists maybe it is, but for us it’s a slow process. We have so many strikes against us– we’re from the southeast, with a young hip-hop scene. Jacksonville, Florida was in The Source magazine once, back when it was relevant, as having the most fickle fans in the United States. Being in the position where we’re learning as we go, it makes what was already a slow grind even harder, but it’s really worth it.”

The results of 2005, while positive, have left the Asamov team hungry for more. “I would still say that, in my eyes, as far as becoming a complete group that, like, I would compare us to De La, we’ve got a long way to go.” Evans’ optimism– and ambition– is palpable. “The release” he says, “was only the beginning.” Marley agrees: “It’s a process of pushing and continually building from what they started. You’ll think 2005 was a joke, compared to what we have set up for 2006.”

6 Hole Records: http://www.6hole.com/ ◼