the eyes have it

by Mike Welch

Monday

Her left eye turns in a little bit, toward her nose. But when you see her from the side she is perfect. You can’t even tell. Her handicap only becomes obvious when her relatives wipe her mouth at dinner, in front of everyone in the restaurant. I’m sure she’s always relied on them, and trusts them when maybe she’s never trusted anyone, but I think she probably trusts them too much. And if she knows trust, then I’m sure she knows embarrassment too. They shouldn’t wipe her mouth in public.

She’s only a little younger than me, 24 maybe, too young to be old, but she dines with the elderly. They trap her in boxy, old lady dresses, and impose their identity on her because she’s too feeble to harvest one of her own. And with their identity comes their age, and their clothes. All dressed the same, her six-person family comes in to Pizza Dive once a week after Saturday night mass, looking old, smelling stale like the church next door, and asking for their “regular table” in my section. She’s too young to have a regular table.

These are my thoughts as I stand next to the old man at the head of their long booth and wait to write down his words whenever he eventually orders for the whole family. I wonder if their imposition of old age isn’t worse than the situation god put her in. At least with a handicap, you still begin young. As I think and wonder about all this, the patriarch and his family bury their faces in their menus, and she, her shoulder against the wall on the far inside end of the booth, stares up at her grandmother, who’s always directly across the table from her. I study the girl’s perfect profile of full lips turning out and away from each other and I think about wanting to kiss her because, from the side, you can’t really tell, until her grandmother wipes her mouth, or ties a bib around her to protect her awful, old, polyester clothes.

He orders and minutes later, I bring food to their table. Rarely does she look up at me when I set her spaghetti down in front of her. Even when I used to warn her, “Don’t touch the plate, the ceramic is really hot,” she never looked up. When I used to say that, her relatives would steal the plate from in front of her to save her from herself, which I don’t like. So now I set down her plate without warning, and ask her if she needs a drink refill. But before she can form the answer-words herself, her grandmother replies, “Yes, more water for her.” I stand there waiting, listening for the girl to answer for herself, or nod or smile to tell me, Yes, water. But she says nothing, and I go and get more water for her anyway because that is my job.

Two nights ago, her family came in as we were closing the restaurant. If you have ever waited tables, you will never have the heart to come in five minutes before close. I was busy mopping the red tile floor in my section, and our other waiter, George, had gone home, so our new waitress, Alana, the Costa Rican girl, stood next to the patriarch, taking the family order. This time though, the handicapped girl didn’t stare across at her grandmother, and she didn’t stare at Alana. She kept her crooked eye on me as I mopped. She smiled and stared at me with her front teeth poking over her bottom lip that’s as thick as a baby’s pinky finger, until I made myself look away, continue mopping, head down. But when I looked back she was still staring and smiling, so I went and hid in the kitchen, talked smack with my manager Tony and laughed with the immigrant kitchen staff, while waiting for the old family to leave.

When, through the service window where the food comes out to us waiters, I saw the family take off, I went back out to my section and continued mopping. As I mopped, head down, I felt a hand from behind, on my waist, soft like slow-dancing, and when I turned around there was the new waitress, Alana, pushing a paper placemat at me. On the back of the placemat was a drawing.

“The girl left this picture of you on the table,” Alana said, her stare shaking my insides. Though she’s worked at Pizza Dive for days now, I’ve ignored Alana, stayed at a distance; afraid she’ll hear my hormones boiling inside if we’re close enough to talk. When we have spoken, for work purposes, she keeps hard eye contact and seems to blink in slow motion, reminding me of sleep, and the compelling softness of dryer-warm cotton clothing. She’s just too pretty: long, black, curly hair hanging down to the back pockets of her corduroy work pants, olive skin as smooth as a landing strip, and 17-years-old. I was already 10 when she was born in some village in the rainforests of Costa Rica.

She came to the U.S. only three months ago and got this job through a friend of a relative who works in the kitchen. Tony, our manager, also manages a network of illegal aliens, setting them up with low-pay work, and then helping them bring their friends and relatives over to work for him as well. Tony is very loyal to his workers. He risks his business license for the guys in the kitchen, but even more so, for the waitresses. The gorgeous, perfect women, Brazilian girls, Guatemalans, Greeks, Puerto Ricans, Costa Ricans needing under-the-table work, even if it means waiting tables despite their Master’s degrees. Tony hires them, helps them, and then, grateful, they sleep with them.

Making sure to stand at arm’s length from her, I took the drawing from Alana and asked, “The retarded girl left this for me?”

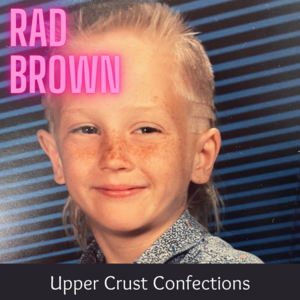

“The beautiful one with a bad eye,” Alana answered, nodding affirmative and blinking slowly. I’d thought I was the only one who’d noticed the girl’s beauty through the mouth wiping and elderly clothes. I silently stared at the picture on the back of the placemat; a crooked line-drawing in orange crayon of a bald man wearing a collared shirt bearing the word “pizza.”

“It’s you?” Alana asked, driving her lazy smile into me.

“Am I bald?” I challenged her, looking down at drawing.

“What it means, ‘bald’?” she asked.

I leaned on my mop, trying to concentrate on the drawing so as not to be overcome by Alana’s sleepy blinking. “It means, no hair,” I said, pointing to the crude, orange circle head of the drawn man, then to my own head. “And I have hair.”

“She no give you hair for the picture,” Alana explained in her pretty broken English. “But she drew the picture in orange because you have red hair.”

Seven years of Florida sun has muted my hair. Now, when I refer to myself as a redhead, most people respond, “You don’t have red hair.”

When I told Alana this she said, “No, no, no. Red hair is the whole person, everything. If your red dies, you are still red forever.”

It was nice of Alana to notice my red hair, to believe in it. It made me comfortable, and soon, I couldn’t help it, she had me glowing and meeting her sleepy eye contact with no unpleasantness.

She added, “My whole family have red hair, but not me and my mother.”

“Really? I didn’t know there were red-heads in Costa Rica.” I said, leaning on my mop and gazing at her.

“How do you know I’m from Costa Rica?” she asked, furrowing her brow then grabbing my mop handle and jerking it out from under my chin. I almost fell over.

We shared a laugh and then I lied, “Tony told me.”

I’d actually overheard her say she was from Costa Rica when she first came into the restaurant to make work arrangements with Tony. Tony interviewed her at the front counter as a handsome young Latin guy leaned against the wall waiting for her. Eavesdropping on them as I worked my section nearby, I also heard her say she was going to be married to the Latin guy a few weeks after New Year’s, when she turns 18. Another good reason for me to stay away from her.

I directed Alana back to the issue. “So, are there a lot of red-heads in Costa Rica?”

She answered, “No, no, no, not many that I see.” Then she rolled her R’s in beautiful explanation, “I have four sisters and a brother, all redhead. People look strange at my brother in Costa Rica, and all the men want my sisters because they are…”

She made circular hand gestures in the air, fishing for the word.

“Exotic?” I offered.

“What is ‘exotic’?” she asked.

“Rare. Not many around. Endangered species.”

“Yes, my sisters are exotic…even old men want to have my sisters.” She stuck her tongue out when she said this, disgusted, and shook her head horizontally. “The old men are …how do you say?”

“Gross?” I guessed.

“Yes, gross.” She nodded vertical. “Always they chase my sisters, even though my sisters are only fourteen year olds. It’s…gross.”

She continued, “I also have a gringo friend in Costa Rica who have red hair. You would like him, he is writer also.”

“How did you know I was a writer?” I asked her. In all my avoidance of her, I knew I definitely hadn’t mentioned my writing.

“Tony told me,” she smiled, then turned away, and I watched her shoulder blades dance under her navy blue polo shirt as she ran away into the kitchen.

Then today, on my lunch break from my day job at the newspaper, I visited the college campus across the street, telling myself I needed to use the resources there to find a new place to live, maybe in San Francisco or New York or New Orleans. Anywhere, I just have to get out of Tampa soon. I’ve been here too long.

But I knew I was really going to campus just to stare at college girls; far away visions of sweet young bodies with underdeveloped brains in them swarming outside the student center, at the art building, at the dance building, at the English department, outside the theater building, some pretty but not sexy, some sexy but not really pretty, all perfect though. I never talk to any of them. I just stare for hours and then leave wound up and disappointed in myself for my inaction. Natalie would think I was an idiot if she saw me. But it’s almost her fault. Those four years of fighting with her left me scared of it all. It just seems impossible now. So, for the past two years since she moved to New York I’ve been staring. I know I shouldn’t do it to myself. It can only damage me, drive me crazy, lingering around campus sniffing and staring, hurting my own feelings. But part of me always feels like maybe something will happen, that someone will see me looking at them, and come talk to me and then I’ll be fine.

So today I went over on my lunch break, and after a half-hour of walking around campus as if I had a purpose, as if looking for a class I couldn’t find, I went to eat lunch. And in the campus cafeteria, I saw the retarded girl from Pizza Dive, her hair in a net and her boxy old lady dress augmented with a long, white work-smock. My first thought was, “She’s strong enough to hold down a job, but her relatives think they need to wipe her mouth for her?”

Student rush hour had passed and she stood static in the empty cafeteria, holding a giant beige lunch tray flat to her chest, looking side-to-side, both ways as if about to cross a street, not knowing what to do, which direction to go. So she went nowhere. She didn’t notice me watching her from the cash register as I paid for my food. She remained frozen in confusion and staring out at nothing, even after I’d found a table and sat down.

As I lifted my pizza to my mouth (lord knows why I actually paid for pizza, why I’d want more pizza despite eating it every Thursday through Sunday night at work), I studied her profile again and thought, “She’s never been touched.” And I chewed, wondering what it would mean to her to be touched, finally. It would mean everything. I understood. After two years alone, I am almost there myself. So, while part of me choked on food and pity, the other part revved, excited as if in love, as if I’d discovered something.

She still wasn’t moving when I rose to cross the cafeteria, straight on at her as she stood looking around trying to discern her situation. As I walked to her I heard Alana’s voice calling her, “The beautiful one” and I continued my trajectory, set on waking the retarded girl up, doing everything for her in that moment, right there, while no one was looking.

But when only two feet of empty air and the bottom of the plastic lunch tray separated us, and she finally noticed me, focused her skewed eyes on mine and smiled bright buck teeth in a face glazed with happy, I was suddenly repulsed, sick knowing that kissing her would only accent a permanent loneliness so deep in her that it was almost lost by now, harmless. And I knew I shouldn’t reach that far into her and stir it. So, in the moment before we collided, I swerved around her shoulder to the left, past her, to the cafeteria exit, out into the parking lot and across the street to the newspaper without ever turning around. And not until I was back at my air-conditioned desk at the paper typing obituaries did I realize she’d probably be in charge of disposing of my un-eaten lunch, cleaning up the pizza mess at my table the way I’d cleaned up hers so many times.