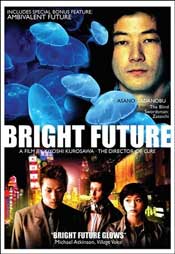

Bright Future

directed by Kiyoshi Kurosawa

starring Joe Odagiri, Tadanobu Asano, Tatsuya Fuji

Palm Pictures

Thanks to American remakes of excellent Japanese horror films (The Ring, The Grudge) and exotically romantic films about Japan (Lost in Translation) there’s been a recent surge of interest in Japanese film. Bright Future is a quiet, but powerful movie that thankfully stands to benefit from a wider share of this enlarged spotlight.

The plot revolves around Yuji (Joe Odagiri) and Mamoru (Tadanobu Asano), two directionless, working class friends living in Tokyo. Both men are so emotionally guarded there’s very little insight given into their motivations or lack thereof. The only clue we’re supplied with it that Yuji used to have rich, fulfilling dreams about his future when he was younger, but that those dreams have recently ceased. The two men’s point of common interest is Mamoru’s extremely poisonous pet jellyfish that he, for reasons unknown, is gradually trying to acclimate from saltwater to freshwater. The pair are disillusioned with their factory job and feel somewhat trapped when their foreman offers them the opportunity to sign on as full-time employees.

Their frustration comes to a head when their boss visits them at Mamoru’s apartment for lunch and reminisces about the forgotten plans of his youth. Yuji is particularly disturbed by his boss’s revelation, while Mamoru remains characteristically inscrutable. Inspired by these events the two independently decide to take extreme action that ultimately ends up in tragedy, destroying their friendship but resulting in a growing relationship between Yuji and Mamoru’s previously long-absent father, Shinichiro (Tatsuya Fuji). Shinichiro becomes increasingly invested in Yuji’s well being, while Yuji obsesses over the jellyfish Mamoru has left in his care. Mamoru becomes the martyr character who sacrifices himself so that the audience is able to embrace Yuji and all his peculiarities, such as his momentary befriending of a gang of teenagers to help him commit petty robbery after hours at the office where he works.

It’s fitting that director Kurosawa doesn’t resolve the film in a straightforward way, but instead, once tragedy strikes a second time against its principle characters, shifts to the group of robber-teenagers wandering aimlessly and carefree on the streets of Tokyo. In the context of what has just played out, the boys’ optimism is already tinged bittersweet even though they have yet to realize it.

Kurosawa’s style is very informal, selecting scenes that casually push the story along without adhering to the standard plot arcs of a drama. This decision gives the film a surreal, episodic quality; almost like a dream, but almost like a documentary. In the accompanying Making Of featurette, Kurosawa goes so far as to state that the filmmaking process consists of “recording several realities and how you assemble those recorded realities afterwards.” The movie was filmed mostly with handheld cameras which lends to the heightened sense of reality, but it still maintains a distinct cinematic quality through a liberal use of dolly and crane shots. One of the film’s strongest qualities is this successful blurring of the realistic and the fantastic, much like the writing of the great Japanese author Haruki Murakami. I can’t think of any higher praise than that.

Palm Pictures: http://www.palmpictures.com/