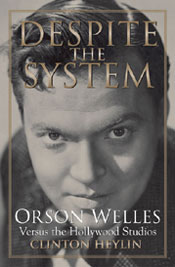

Despite the System: Orson Welles Versus the Hollywood Studios

by Clinton Heylin

Chicago Review Press

So maybe, scanning the cover of Despite the System for the first time – that is, once you’re finished wrenching your eyes from Welles’ piercing gaze in full, beautifully manic/smoldering glory as depicted in the remember-him-this-way cover photo – you’re a little surprised to see that the author of this weighty tome on cinema’s purported enfant terrible is none other than rock scribe-par-excellence Clinton Heylin. I know I was. Having his read his excellent From the Velvets To The Voidoids pre-punk anthology, it seemed a bit of an odd volte face for him to switch focus from the grimy, shambolic, raw music of NY punk to the towering visual majesty and ambitious perfectionism as typified by Welles at his best. From the garage to the heights of San Simeon? Yeah, listen, it makes total sense. Beyond punk, Heylin’s written extensively on Bob Dylan and Van Morrison. See a trend, a common thread here? Bingo. Mavericks, every single one of them. “Difficult” geniuses hell-bent on pursuing their own vision in spite of everything – friends, foes, the marketplace, the audience – who cares? And when you get down to it, when you’re sick of Bob Dylan doing Victoria’s Secret Commercials, Van Morrison nattering on about skiffle and CBGBs relocating to Vegas (Baby, Vegas!), then you’ve got to search out your aesthetic/artistic purity fix elsewhere. Gotta look around carefully to find someone who wasn’t co-opted, corrupted, or just plain ol’ cashed-in. To find the hard stuff, maybe you have to leave the world of rock and roll entirely. Film may seem an unlikely source, especially when you try to choke back the vomit as you survey today’s “glittering” scene of stars, but if you look back, far back, in the distance an eldritch figure comes into view. Because let’s face it, if you want the pure fix of maverick, you need look no further than Hollywood’s dark prince, Orson Welles.

What, Orson Welles? The man of a million cameos? The voice of Unicron on the Transformers movie? Wasn’t he the guy who got spoofed on the “They’re full of delicious green pea-ness” sketch on the Critic cartoon? Don’t be a dick. As Heylin full well knows (and proves), Orson Welles is better than any rock star. He sacrificed everything in pursuit of his artistic vision, and while that meant nothing but heartbreak and despair, tempered with the occasional euphoric highs of creation, for us, it left a body of work that is still groundbreaking and beautiful today. When’s the last time you heard a rock star say something like, “I’m not interested in […] posterity, or fame, only in the pleasure of experimentation itself. It’s the only domain in which I feel that I am truly honest and sincere. I’m still waiting for your answer.

As dedicated fans and film scholars still try to sort out the shambles that studios made of films like the Magnificent Ambersons and The Lady From Shanghai, culling together new cuts from snips left on the cutting room floor and cryptic shooting notes, one cannot help but be struck at the parallels between much of Welles’ post-_Kane_ work and that other great “lost” masterpiece, Brian Wilson’s Smile. But to try and find personal parallels between Brian Wilson’s Little Boy Lost and Orson Welles does grave injustice to both. Orson Welles was an altogether more driven and focused individual. Sweeping into Hollywood as its Janus-faced boy-genius-savior/dark-prince-destroyer, the young Welles was lured there by a dying film company (RKO) that offered him unparalleled creative control via an unprecedentedly libertine contract. And save them he did, with the incomparable Citizen Kane, even today still seen as the Rosetta Stone of modern cinema. But one can only assume that they were instead looking for him to make The Ghost and Mr. Chicken over and over again, because from that point on, RKO and every studio hence tried to destroy him. Film after film was either yanked away from him (beginning with the one right after Kane, the Magnificent Ambersons) or simply cancelled outright midway through (It’s All True). One can only take so much, so a despondent Welles fucked off to Europe to pursue his side avocation as an actor and try new projects (like Shakespeare). When he finally returned to work on Touch of Evil, even that was spoiled by interference. And though Welles would continue working on projects up until his death, you could tell that was the crippling blow. He even brought Charlton Heston to the top of his game. How much can a man endure? Despite the System dredges it all forth in painful detail.

Despite the System focuses squarely on the tussles with studios, a novel angle, and though there are gaps (personal life only briefly alluded to, some projects and acting jobs passed over entirely) the book is the richer for it, as a portrait of fights, frustration, mindgames, struggle… and Heylin covers it with all the relish and measured disgust of one who’s familiar with all the dirty backroom deals, broken promises, knifed backs and soulless reptiles that populate the music biz – Heylin’s seen this story a million times before and it still sickens him. Because it kills art and beauty.

The details of Welles’ working process are a joy to read, even amidst constant delays and obstructions from the “money men.” All these years later, the anecdotes and memo notes still radiate this incredible creative vitality, which makes every betrayal and forced compromise all the more heartbreaking and cruel. Collaborators, stars, film crew alike all speak of time spent working with Welles as either a career high point or as a joyous challenge to create something new and visionary, trying to stretch the limits of film to their very breaking point. All things considered, Despite the System might just be one of the best punk rock books ever written.

Chicago Review Press: http://www.chicagoreviewpress.com/