Mexican Calendar Girls (Chicas de calendarios mexicanos)

by Angela Villalba, foreword by Carlos Monsiváis

Chronicle Books

In houses where the wall calendar is more than a benign or inconspicuous object, where it is hung to be as decorative as it is practical, it has mutated into a means of commodified, neatly packaged self-expression. These wall calendars will often tell you more than the date, the day of the week and upcoming holidays; they will tell you whether their owner likes American muscle cars or Gary Larson cartoons, the castles of Scotland or, that indelible hallmark of questionable taste, Anne Geddes photos. The latest crop of online photo sites and desktop organizers take this to its inevitable extreme, offering the most convenient personal statement yet possible in this area: the annual calendar that includes one’s own memorable dates and photos.

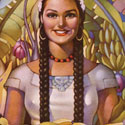

In Mexico the wall calendar traditionally held a different role, one that was more prominent and varied than perhaps anywhere else in the world. The wall calendar transcended its boring numbered grid there, too, but rather than serving as a personal statement on its owner’s behalf it was instead a symbol of national and regional pride, a purveyor of nostalgia, romance and myth, a form of eye-catching populist art, a manipulative tool of tourism and industry and even a source of mild titillation. In her straightforwardly titled book Mexican Calendar Girls: Golden age of calendar art 1930-1960, Angela Villalba documents – in corresponding English and Spanish translations, no less – the interesting history of the Mexican wall calendar while reproducing the strongest evidence for its uniqueness: the images themselves. This is one instance where a reader would be fully justified in judging a book by its cover, here a colorful image of a pretty, red-lipped girl with dark, impossibly straight braids and pert nipples holding a basket full of meticulously arranged fruit before her. Mexican Calendar Girls is packed with sumptuous and suggestive images like this one.

All the same, it would be wrong to think on the basis of its cover (and its title, for that matter) that this book consists entirely of brightly colored paintings of voluptuous women intended for macho ogling and pubescent fantasies. Mexican Calendar Girls yields a few surprises, a few of which can be found in the “Macho women and cowgirls,” or “Adelitas y charras,” section. Here you’ll find Antonio Gómez’s painting of a trio of deadly serious soldaderas, or female soldiers, taking aim at a group of unwitting male enemy soldiers below. One of the women intently aims a six-shooter though a flowering cactus. The others, bandoliers slung over their shoulders, hold rifles with expert precision. Although this image complemented a calendar advertising firearms, these female models showcasing their weapons’ utility are nothing like objectified gameshow bimbos. Josep Renau’s female figure in “Campamento” (“Camping site”) doesn’t hold a rifle; she has a lantern-jawed man on her arm. But with one hand on her hip, she regally surveys the campfire and the host of gauchos sitting beneath her. There is no coy, wilting femininity here.

The surprises also run in the opposite direction, with images that surpass mere pin-up girls and would tempt even the chaste Puritan hearts north of the border. Angel Martín’s “Princesa Maya” depicts a woman in an opulent feathered headdress and very little else. Behind her a virile, muscular chief (who is wearing considerably more) approaches with a steaming bowl of… some ancient Mayan aphrodisiac perhaps? The transparent sombrero that gives Aurora Gil’s painting its name conceals as little of its curvaceous subject as her tan stockings and black lace arm covers. These unabashedly sexy paintings portray another, more lascivious side of femininity, as well as an aspect of Mexican culture that is at one remove from the rainbowed courtship rituals shown in Armando Drechsler’s “Jarabe Tapatío” (“Mexican Hat Dance”), W. Soto’s “Enamorados,” or “Lovers,” and Eduardo Cataño’s highly romanticized paintings of fairs and celebratory occasions. What might not be immediately noticeable is how un-exotic many of these females look to the contemporary reader. Save for A.X. Peña’s stylized native women, many of these subjects have the safe, familiar North American and European beauty of leading ladies from Tinseltown’s heyday. As cultural critic Carlos Monsiváis notes in his foreword, this was deliberate. “Malinche, Cortés’s mistress and translator, could resemble the Hollywood actress Anna May Wong, and the Mayan princess could evoke the sumptuousness of María Montez in Arabian Nights … The calendar art mixed Hollywood fantasies and Mexican legends, which in turn transformed into movie themes.”

Owing to the mass-produced, ephemeral nature of the calendar images (to give some idea, the labels of the illustrated bottles and cigarette packs were often left blank for manufacturers to insert their own logo), many of the original paintings were not appreciated for either their artistic merit or their historical significance, and along with the names and biographies of some of their creators they have been subsequently lost. Their canvasses were reused for the following year’s batch, or they were painted with cheap materials that quickly cracked and faded. This makes Villalba’s book – a labor of love assembled from her personal collection of more than 250 calendars and featuring informative bilingual text on printing technologies, major publishers, calendar types, collectors advice and biographical sketches of calendar artists who have survived age and obscurity – all the more impressive. Mexican Calendar Girls is at heart a coffee table book, but like the beautiful calendar art it chronicles, simple categorizing doesn’t do it justice.