Monaural Masters

Charles Mingus Sextet with Eric Dolphy – Cornell 1964 (Jazz Workshop/Blue Note)

by Shelton Hull

Since his death of arteriolateral sclerosis (aka Lou Gehrig’s Disease) in 1979, Charles Mingus’s reputation as one of the towering figures in jazz music history has only grown by leaps and bounds. Illness had slowed his output, and the marketplace has dealt blows to his music’s prominence in American culture, though his influence in Japan and, most especially, Europe has never waned. But by the time Joni Mitchell won a Grammy Award in collaboration with Mingus in the late ’70s, many contemporary audiences and critics were left asking, “Now who, again, is Charles Mingus?”

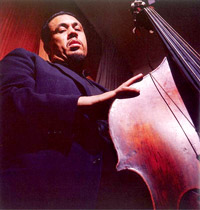

Thirty years later, everyone knows who he is. Mingus was one of the music’s most important composers – as important, in his way, as Charlie Parker or Thelonious Monk. He is widely regarded as the key stylistic heir to Duke Ellington, who was both his main influence and first big-time employer. Mingus and Max Roach founded Debut Records, one of the very first artist-owned labels in any genre. With Ellington, they waxed Money Jungle for United Artists in 1962. He played bass on the legendary Masey Hall set in March 1953. Above all else, Charles Mingus was the greatest upright bass player ever.

With all due respect to titans such as Jimmy Blanton, Ray Brown, Ron Carter, Paul Chambers, Jimmy Garrison, Charlie Haden, Percy Heath, Dave Holland, Scott LaFaro (whose “Solar” solo with Bill Evans’ trio in 1961 is the Rosetta solo of modern bass) and others, nobody can match Mingus for pure technical proficiency. Mingus had the kind of hands one might see on a good defensive lineman or a basketball player like Wilt Chamberlain: big and muscular. His fingers delivered awesome power to the strings, and their span allowed him access to the fullest chromatic range of the bass. Spots that some bassists would reach to hit with a middle finger, Mingus could hit with a pinky. Double-stops, triple-stops, quadruple-stops – he could play four different notes on four different strings simultaneously. (The solo that starts “Autumn in New York,” from Mingus in Wonderland, is just about definitive.)

Mingus was reportedly one of the hardest bandleaders to work for, a composer who demanded technical mastery from his collaborators. He allegedly laid out trombonist Jimmy Knepper for some studio error in 1963, and was fired by Ellington for threatening “Caravan” composer Juan Tizol with a fire axe 20 years earlier.

In a career that lasted some 35 years, the finest Mingus groups were probably those he fronted in the early 1960s, which produced some of the finest small-group jazz ever recorded. Cornell 1964 captures one of his best lineups in circumstances that allow their qualities ample display. It makes a good introduction to Mingus’ music, while his serious fans will find it irresistible, and perhaps even revelatory.

Mingus’ career as a leader was defined by his relationships with two men whose stamp is all over his music. Drummer Dannie Richmond was an inextricable part of the Mingus sound for almost 25 years, and it was he who carried the torch for Mingus after his death; if not for Richmond’s efforts in the 1980s, our contemporary understanding of Mingus would be vastly incomplete. Never was there a better bass-drums combo.

Richmond’s name is obscured by having made all of his key recordings under the Mingus umbrella, continuing until his own death in 1990. He is doubtless one of the great drummers – the easiest comparison would be to Mel Lewis, who could hold a group tight to the beat without an ounce of wasted motion. To hang with Mingus in all those contexts for so long was a massive undertaking, and he handled it fine.

Even though he’s pretty well-known, Eric Dolphy is nonetheless one of the most underrated musicians in jazz history. Part of the problem is that, while Dolphy made a number of good albums in his short life, his best work invariably appeared on albums by other people. Dolphy was MVP of the jazz world in 1961, appearing on no fewer than 18 albums that year, including his own Out To Lunch (Blue Note) and the seminal live set recorded at the Village Vanguard by John Coltrane. He was a sideman nonpareil who brought heavy fire to every session he appeared on. Charles Mingus Presents Charles Mingus (Candid, 1960) is arguably the best Mingus album, and it reaches that level in large part because of Dolphy’s contributions. In fact, it’s a good idea to listen to that album again before jumping into Cornell 1964; the progression is dramatic.

This is serious music, but there’s nothing fancy or complicated. Three Mingus originals and two Ellingtons, rendered by an outfit with stamina to spare. The group also includes trumpeter Johnny Coles, from Baltimore, and tenor saxophonist Clifford Jordan, who came out of Chicago as a contemporary of Sun Ra’s ace tenor, John Gilmore. With Dolphy on alto sax, bass clarinet and flute, that makes a frontline of four – just right. Any more and the sound might have washed out on the monaural master.

Boston Pianist Jaki Byard, another longtime associate of Mingus, begins the set with a solo entitled “ATFW You,” a nod to Art Tatum and Fats Waller. Mingus makes it two, with a coy, tensely restrained version of Ellington’s “Sophisticated Lady” (which is a nice demonstration of Mingus’ skills) before the group dives into 30 minutes of “Fables of Faubus.” An unrelenting advocate of racial justice, Mingus wrote the song in protest of the segregationist governors of his time. The liberal audience sings along with the lyrics, which were so controversial in 1959 that Columbia would only let him record the song instrumentally. It is the proverbial emotional roller-coaster. Byard quotes “Danny Boy,” “Yankee Doodle,” Chopin’s “Funeral March” and “Lift Every Voice and Sing” – all of which are appropriate to the occasion. The ballad original “Orange Was the Color of Her Dress, Then Blue Silk” brings some smoothness to the proceedings.

The most visceral moment comes an hour into the set, as Mingus counts out the tempo for “Take the ‘A’ Train.” Billy Strayhorn’s classic found its way into more sets in later years – a version recorded at Slug’s NYC in 1970 stands out – but this must be one of the earliest yet known. Running over 17 minutes, it functions as a sort of tonic, a palate-cleanser between the meat of the set, the 45 minutes of Mingus tunes on either side of the song. Jaki Byard offers up a little capsule history of the piano tradition to that point before yielding to the reeds. Throughout you’ll hear Mingus saying stuff like “It’s all right” and “Don’t worry about it” as he prods his troops ahead. Mingus and Richmond then take over for five minutes, leading the audience through the intricacies of the duo’s music “conversation.” This is the kind of interplay that nobody else can approach, and Cornell’s hipster set is just so audibly owned.

Disc two begins with “Meditations,” one of Mingus’ most ambitious long-form works, thirty minutes of moody brooding and contemplation. “So Long Eric” was intended as a “bon voyage” before Dolphy embarked on touring Europe, where his style had a crucial influence on the jazz to emerge from that continent. It was not meant as a permanent goodbye, but it was, because Dolphy died just weeks later. Had Dolphy lived longer, he would have been the major figure of the “avant garde” scene to emerge later that decade – Anthony Braxton, Archie Shepp, etc. He’d have probably been involved in John Coltrane’s Ascenscion-era sessions, too.

The concert ends with a bouncy, ironic take on “When Irish Eyes Are Smiling,” which manages to achieve a wistful, valedictory feel, followed by ten minutes of Fats Waller’s “Jitterbug Waltz” to close, with Dolphy’s flute out front and Byard twinkling the ivories like Liberace. It’s a very happy way to wrap a set otherwise marked by the tragic, premature end of the brilliant Mingus/Dolphy alliance.

When newfound live recordings of old masters hit the market, the first question usually asked by experienced listeners concerns the sound quality. Sue Mingus found the tapes decades after their recording, and Blue Note used one of the top reissue producers out there, Michael Cuscuna (who co-founded the indispensable Mosaic Records), to put the spit-and polish onto what was already a pretty decent master tape. The packaging is simple, but pleasant, and Gary Giddins’ liner notes are a model of the style.

Another hero in the Mingus story is his second wife, Sue Graham Mingus, who provided crucial support in his last years and who built the Mingus Dynasty, which is still an active organization, by sheer force of will. It is she who found the tape of this concert, which had lain dormant in a box, undocumented for 40 years. The results – on two discs, with 10 tracks, averaging over 13 minutes each – is peak-form Mingus, with several key collaborators, stretched-out in a manner rarely documented so well on record or disc. This is about as close as we can ever get to the experience of hearing this group as it was intended to be. Two years in a row, Blue Note has mined jazz gold from the ether.

Blue Note: http://www.bluenote.com ◼