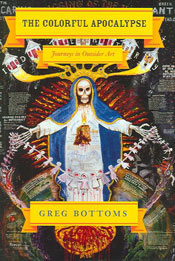

The Colorful Apocalypse: Journeys in Outsider Art

by Greg Bottoms

University of Chicago Press

The Colorful Apocalypse: Journeys in Outsider Art is not a pretty art book. In lieu of reproductions of paint-spattered apocalypse (other than one on the cover), settle in for a part-memoir, part-interview series, part-travelogue. Also, don’t presume that the author, Greg Bottoms, has expertise related to outsider art. Neither art historian, nor psychologist, nor theologian, he is, in another sense, an outsider, too, but one (we hope) with the objectivity to demystify what has been sensationalized–outsider artists and their radical Otherness, which too often typecasts them as the crazies in folk art’s attic.

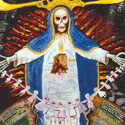

“Outsider art” refers to work by those usually lacking formal training and who create and sometimes live on society’s fringes. Even more key, a desire to sell their art motivates outsider artists much less than an all-consuming personal, spiritual, or therapeutic need to create it. Visionary outsider artists (the focus of The Colorful Apocalypse) claim the same mental phenomena as religious prophets, i.e., visions sent by God. Manically scrawled scripture, blood-soaked martyrs, Revelations depicted in electrifying colors–visionary art vibrates with a spiritual purpose that almost seems to burn the artist alive.

As Bottoms explains, apocalypse usually starts dress-rehearsing in these artists’ heads right around the time that unthinkable trauma wrecks their normal lives. So tantalizing are the artists’ Job-like tales, they frequently eclipse their own work, with artist bios detailing an acid trip gone horribly wrong or the grisly murder of a daughter or a normal Sunday in church turned into a vision hand-delivered by the Devil himself. But therein lies the trouble for Bottoms–and the motivation for his book. As the brother of a schizophrenic (the focus of his autobiographical memoir Angelhead), he has a clearly expressed stake in understanding mental illness. He views visionary outsider artists as marginalized, their messages distorted, their pathologies glamorized; so equipped only with his objectivity (however possible objectivity is nowadays), his personal experiences living with mental illness, and a bibliography of the art counterculture (which contextualizes outsider artists with Jean Dubuffett’s art brut, the Dadaists and Surrealists, Situationist Internationale and movements like the Beats and even punk), Bottoms revisits his old Southern stomping grounds to interview outsider artists, their families and fans.

The Colorful Apocalypse begins with Reverend Howard Fincher, a Georgia artist who put outsider art on the map when he attracted the attention of R.E.M. Fincher’s Paradise Gardens, an al fresco installation around his country home in Pennville, featured in the band’s “Radio-Free Europe” video. Michael Stipe also commissioned him for the cover art of The Reckoning, as did the Talking Heads for Little Creatures. After overcoming the loss of siblings at a young age, Fincher created compulsively to bring a spiritual message of hope so powerful he awoke Bottoms and the rest of his college hipster set to the outsider art phenomenon. Unfortunately, by the time Bottoms started his research, Fincher had passed away; so the book includes interviews with Fincher’s daughter (who now stewards Paradise Gardens) and some closely associated admirers.

One admirer is an outsider artist herself, Myrtice West, whose own early brush with death and later miscarriages made her withdraw to the family barn where she would continually draw Jesus. But it wasn’t until her only daughter moved away with an abusive husband when the urge to paint consumed West wholly, a period responsible for her first Revelations series (which, bittersweetly, brought appreciative swooning from the art world and artistic success). When Bottoms plies West for an artist statement, she assesses people let Satan loose and ruined the world. Not a rosy prophecy but given the horrific conclusion to her daughter’s story, her end-times theory holds credibility like a silent newborn.

When Bottoms moves on to William Thomas Thompson, a millionaire who lost his wealth and suffers from an excruciating nerve disorder, The Colorful Apocalypse becomes its most interestingly messy. Through lengthy interviews with Thompson, whose Christian fundamentalism, conspiracy theories and other ideological no-no’s puncture the idea of an artistic savior pilgrimaging from rationalism to enlightened spiritualism and championing art inspired by humanity’s return to an Essential self, Bottoms discovers many messages in outsider art really do not jibe with liberal audiences–at all. But the mystique of the art, the superficial novelty of its 180-degree turn from a mainstream perspective, blinds fans to its bilious rage and paranoia. Secular collectors seem willing to overlook anti-abortion messages for an intensity of vision that hasn’t been around since Van Gogh. Bottoms struggles to resolve such contradictions, hashed out by his tense conversations with Thompson.

Thompson’s collaborator, Norbert Kox, converted to Christianity after a bad LSD experience at a party with other Outlaw bikers. Although Kox is the only artist out of the four to have attended art school, he fits the outsider stereotype more than any other: residing in an obscure country outpost, Kox goes for weeks at a time without seeing anyone; Bottoms can barely navigate the clutter of artwork and salvaged sculpture supplies in his squat, the abandoned remains of the only shop in town. Despite his former biker gang affiliations and the mutilated doll parts strewn around his house, Kox comes off as gentle and genuinely nice. However, since publication of The Colorful Apocalypse, Kox has denounced Bottoms’ portrayal of him and Thompson on the message board for the book’s Amazon.com entry.

So does The Colorful Apocalypse succeed in its mission? Is the reader left with a deeper understanding of the individuals who produce outsider art? As someone with no background in art or psychiatry, Bottoms is one outsider speaking to other outsiders, hoping this arrangement will reveal who the artists are, what inspires them to create the art they do, beyond the sensationalism of their extreme beliefs. Sometimes this approach works: Coming from the South, where many outsider artists are based, Bottoms casts diamond insights about their environment, including the unsettling notion they might just be extensions of “Southern, white, right-wing, tribal paranoia.” But the book’s unresolved questions, along with this possibly litigious argument between the author and his subjects, shows nonbelievers can never completely understand followers of gospel. Luckily, empathy prevents us from seeing each other entirely as strangers: suffering can recognize another soul in pain, another’s hunger for meaning, for the pain to mean something, anything. Even if readers identify more with Bottoms (who had his own cross to bear), they just might envy his subjects more because at least their sorrows fit into a meaningful story, a frame for life’s grand disappointments. Plus, they have some astonishing art to show for it.

Chicago Review Press: http://www.chicagoreviewpress.com