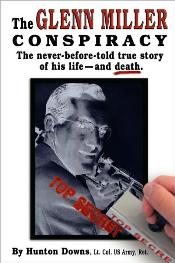

The Glenn Miller Conspiracy: The never-before-told true story of his life – and death

by Hunton Downs

Global Book Publishers

World War II, which killed at least 50 million people, was arguably the most important event in the history of the world. It was the moment at which the United States assumed its traditional “superpower” status, a top ranking that evolved upward, to the point of being “the indispensable nation” after the Soviet Union collapsed. As such, WWII retains high interest among the American people, even now, some 70 years since the shooting started, and at a time when our superpower status faces unprecedented challenges. Barely a year goes by without some new, award-winning treatment of some aspect of the war, and there is almost always writing on the subject near the tops of best-seller lists.

A key aspect of the war, one that distinguishes it from the other military conflicts this nation has been involved in, is that celebrities were involved. This is also true of the world war that preceded it, but only WWII saw men stepping aside at the peaks of their powers to seek out serious combat duty. Their record was impressive, adding all kinds of texture to the larger story. Baseball great Ted Williams became a fighter pilot; jazzman Buddy Rich fought Imperial Japan with the Marines. The film industry devoted a huge chunk of its time, money and manpower – including all of its top stars – to the production of pro-American propaganda, many of them taking military commissions to do such work in the field. Creative talent across the board, on both sides of the Atlantic, was redirected toward the Allied cause, and hundreds of entertainers (most famously Bob Hope of the USO) risked death in making treacherous journeys to visit soldiers fighting abroad. In fact, the first female casualty recorded by the US Government in that war was actress Carole Lombard, whose plane crashed into a mountain between shows. Her husband, Clark Gable, immediately enlisted, and issued receipts of his own.

It just so happened when I was informed of the existence of the selection being reviewed at hand, I was reading another book about the subject: Jimmy Stewart: Bomber Pilot (St. Paul, MN: Zenith Press, 2005). Author Starr W. Smith, who served as a combat intelligence officer with the Eighth Air Force in England before working with top officers like Hap Arnold, Jimmy Doolittle, Carl Spaatz, and future President Dwight Eisenhower, offers up the definitive history of Stewart’s legendary service in the Army Air Corps. It turns out that Stewart, by all accounts one the most gentle souls to ever get ahead in the ruthless years of old-school Hollywood, was for several years a deadly good pilot of B-24 Liberators. He led his own squadron through 20 missions with the 445th bomb group, and later became a group operations officer for the 453rd bomb group. Most missions took him directly through the heart of German territory, including Berlin. Stewart ultimately served 27 years in the Air Corps, Air Force, and Air Force reserve, including nearly five years active duty and two years of aerial warfare on a daily basis. He would retire as a Brigadier General in 1968, but not before earning a “Mach 2” pin at the controls of a B-58 Hustler in 1960. And from there we turn to Major Glenn Miller.

The premature death of Alton Glenn Miller (1904-1944) ended what had been a hugely successful music career that was at its peak when Miller volunteered for the war. Subsequent fans – weaned on bop, post-bop and the “progressive” orchestras led by Stan Kenton, Claude Thornhill, Gene Krupa, and Billy Eckstine (not to mention the serious swing bands of Basie, Ellington and others) – tended to tag Miller’s music, rightfully or not, as the embodiment of saccharine dance-band commerciality. Death perhaps robbed Miller of the chance to place that music in a fuller context.

For years – generations – the commonly-accepted story regarding what happened to Miller was the one put forth initially by the United States military: that Miller died in a small plane during a failed crossing of the English Channel, en route to a rendezvous with his band in France. It was presumed the plane crashed in bad weather. Decades later, one of the Allied aviators working that territory back then came forward, claiming the bomb from his plane had accidentally obliterated Miller’s when it was jettisoned following an aborted bombing run. This created dual theories that may or may not intersect, of which neither has more than a smattering of suspiciously superficial “evidence.”

The Glenn Miller Conspiracy offers a new theory, far more compelling, with a lot more data to back it up: Rather than being simply a musician in uniform, the victim of a plane crash between gigs (of which there is a long, tragic history in American music), it may be that Miller was doing the kind of work that makes Wagnerian opera look like a Jerry Lewis movie. Miller was among a handful of celebrities marked for death, on sight, by the Nazi high command, perhaps as high as Hitler himself. The most notable would be singer/actress Marlene Dietrich, among the first prominent native-born Germans to come out publicly against the regime. Author Hunton Downs places her in the same circle of German-speaking celebrities as Miller – people whose faces and voices could be used to drive down enemy morale, while helping to foment dissent and resistance among their troops and civilians. After victory, they could help establish the credibility of an Allied occupation force. History has shown success on all such fronts.

Miller, who wore the markings of a Major, had organized the band to entertain troops serving in the European Theatre; the dozens of recordings made during these years constitute a major component of his subsequent legacy, in part because of the clear role his music (and that of many others) played in sustaining the morale of soldiers and civilians alike during the bloodiest war ever fought on Earth. The massive, all-pervasive attrition of that conflict is beyond the comprehension of anyone who wasn’t there to see at least part of it firsthand. It was a war fought with no restraints and no restrictions, limited only by technological shortcomings of nations and the mental mistakes of mortal men.

Miller performed almost exclusively for the front-line combat solders who had established a beachhead on the southern coast of France, then pushed all the way into the heart of Berlin itself, in less than one year. His death occurred almost to the moment as the “Battle of the Bulge,” which claimed some 85,000 American lives. That is the context in which author/soldier Downs fixes Miller, musician/soldier. Basically, Downs claims that Miller was a player in high-level (yet super top-secret) negotiations between US and German generals to end the war in Europe six months earlier than it did.

This is explosive stuff – literally – for obvious reasons. The last six months of that war were arguably the most awful of all: the firebombings of Dresden and Tokyo, the Bulge, Guadalcanal, Iwo Jima, Kamakazis, two nuclear bombings, civilians being killed by the hundreds of thousands in a single day – and, let’s not ever forget, the acceleration of the Holocaust toward what the Nazis called a “Final Solution” with maybe a million Jews killed in 1945 alone. Downs implies that Miller was engaged in a plot that may have spared humanity the ultraviolent death spasms of the Third Reich.

It didn’t work out that way, unfortunately, and this is really the story that Downs deigns to disseminate – a tale of intel and counter-intel, agents and double-agents, spies and spymaster, a tale of how the actions of a few men, possibly independent of their own central governments, could influence the lives and deaths of thousands. It is a compelling story, delivered in the style of a hard-boiled pulp detective novel, wherein Downs is the private dick digging for the truth through the files and folders of three countries.

Glenn Miller’s rapid rise to dance-band supremacy, with hit songs that defined an era for millions of Americans, obscured his legitimate jazz credentials. His trombone chops were maligned even by Miller himself, yet they were sufficient to land him in the pit bands for two landmark Broadway shows, Strike Up the Band and Girl Crazy, both with lyrics and music by the Gershwins, who had their pick of the famously deep talent pool in 1930s New York. He worked as writer, arranger and sideman for a solid decade before starting the uphill climb with his own band, sharing stages and bandshells with some of the giants of American culture, including Krupa, Burns & Allen, Eddie Condon, Ethel Merman, Dorothy Dandridge, Jimmy and Tommy Dorsey, Bud Freeman, Benny Goodman, Coleman Hawkins, Red Nichols, Ben Pollack, Pee Wee Russell, the Nicholas Brothers and Bill “Bojangles” Robinson.

Miller belonged to a time when commercial success was not necessarily the mark of artistic compromise it is perceived as being today. The industry was different, and the country’s aesthetic values were different. While his groups were never distinguished by the raucous swing and rhythmic density of his contemporaries (namely his close friend Goodman, with whom he shared multiple commonalities), the music did not suck, by any means. Miller was, above all else, a world-class arranger who knew how to maximize the sonic potential of his instruments. He shifted the responsibility for carrying the melody from brass to reeds, creating a “sweet” sound punctuated by trumpet riffs. He was expert at the utilization of harmonic counterpoint, which added layers to the sound. As millions of old people (and hundreds of young hipsters) will tell you, Miller’s music is eminently danceable. Did it swing? Not like Basie, Ellington or Goodman, but yes, it did.

Dying in 1944 robbed Miller and his fans of the chance to see his methods in the context of the new music world that opened up after the war. The idea of a Glenn Miller group recording in stereo, for a ten- or 12-inch LP, is so savory it makes mouths water. He was huge in the 1940s, moving vinyl by the truckload but never acknowledged in his time as the master he was. Had he lived ten or 20 more years, there would have been no question; he’d be regarded on the level of a Stan Kenton or Gerald Wilson, at least, if not a Gil Evans. The possibilities of collaboration with other musicians opens up new doors when it comes to fantasy-booking. Like most bandleaders, Miller may have acceded to the economic pressures and done some small-group work, and we’ve seen how useful those years were to other band leaders.

Whether it’s novels or nonfiction, a good story needs a good balance of well-defined personalities, and The Glenn Miller Conspiracy is a case in point. Miller is obviously a solid hero figure, and Down’s depiction raises him to James Bond-y levels, while his supporting cast among the Allies consist of giants among men. The villains here are equally compelling, in particular the infamous Otto Skorzeny, a friend and bodyguard of Hitler’s who ran his own commando team specializing in audacious operations that, to modern eyes, read as the stuff of movies. (If he weren’t a Nazi, his rescue of Mussolini in 1943 – using gliders! – would have gotten the Treatment decades ago.)

A recurring theme in Downs’ story is the skill of the Nazi propaganda machine, an aspect given short shrift in a history written by us, their victorious foes. Official sources would be reluctant to admit, as Downs claims, that Nazis had infiltrated the highest levels of the Allied command structure, not just in proximity to the battlefield, but as far behind the lines as London and even Washington DC. By 1944, the war’s end was in sight. After the successful (albeit horrific) invasion of France, Allied soldiers began clawing their way deeper into the continent, while Russian troops were squeezing Germany from the other side. Hitler had begun to alienate himself from top commanders whom he blamed for the failure to crush Britain and repel the Americans. He barely survived an assassination attempt run by disgruntled elements of his own officer corps (depicted in the Tom Cruise movie Valkyrie), and retaliated with a vicious purge that only intensified the private doubts many top Germans were having about his leadership.

The death of General Erwin Rommel was a tipping-point that made it possible for the Allies to imagine the Germans had seen enough. Rommel, known as “The Desert Fox”, was the famous commander of German tank forces in North Africa, and he had developed reservations about the soundness of his superiors. After being nearly blown to bits inside his own bunker, Hitler’s paranoia (a common trait of dictators) reared like no one had seen since “The Night of the Long Knives” in 1934, where he purged the Nazi Party of thousands, killed off all political opposition and formally consolidated power. He perceived Rommel as a threat, so in classic authoritarian fashion he was hit with trumped-up treason charges and given the choice of an honorable suicide or a long and painful process that would culminate in his death anyway.

While the first purge met with the tacit acceptance of his colleagues, the second made them think they could be next, and apparently some Germans began negotiations with Allied officials at that point, while professing public loyalty to the Nazi cause. The plan was for Hitler to be killed or captured by the military, and a new leader would be named who would then surrender to the Allies under terms more favorable than the “Unconditional Surrender” being demanded by London and Washington. In the process, these Germans, and friends and family, would be smuggled out of Germany to avoid reprisals from the Fuhrer’s fanatics – and, most importantly, to keep them out of the hands of the Soviet Red Army, which was on its way to Berlin, minds fresh with the memories of 20 million countrymen killed in a war that, for them, began with a German double-cross. Among this group were the scientists working to develop futuristic weapons for Hitler, led by rocket man Werner von Braun, whose efforts led directly to the development of America’s space program. Saving such brain-power from imminent seizure by the Soviets was one of the major victories-within-the-victory for the United States, one that is paying off to this very day.

The fates of those Germans who fell under their control was awful: torture, death, mass expropriations of the little resources left, and 44 years of virtual slavery as part of the Soviet Bloc. The choice was clear. Germany expected no mercy from Russia, so their only hope lay with the United States, which allowed their portion of Germany relative freedom post-war, and which even spared the lives of several defendants at Nuremberg. Downs claims that Allied efforts to forge a truce were intercepted by the Nazis. While Hitler lost the scientists, the truce never happened, and the most extreme violence in the history of humanity lay just ahead. Downs further claims that Miller was never in that disappeared plane, but that he made it to Paris, where he was murdered before he could relay crucial information from Eisenhower to representatives of the dissident Germans, and that the plane crash story was made up afterward to obfuscate the fact that (a) the US and Britain were negotiating with Germany independently of Russia, and (b) that the Nazis had infiltrated the office of the Supreme Allied Commander.

Like the hero of his story, Hunton Downs is another member of that “Greatest Generation” that won the war and helped save the world from death or slavery. A native of Baltimore, he grew up in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia. He opened the first radio facilities while a student at Virginia Tech, before joining the Army, serving on the staffs of two major figures in the eventual allied victory: Generals Omar Bradley and David Sarnoff. The former was roughly third-in-command in the European Theatre, behind Generals George Marshall and Dwight D. Eisenhower, while the latter founded both the RCA-Victor record company and NBC, positions from which he coordinated communications and propaganda activities in some areas. After the war he won awards for his coverage of the postwar world. He was in Berlin when the Nazis surrendered and noted the first falling frosts of the Cold War. Twenty years later, his work on the Vietnam War earned him a Pulitzer Prize nomination. All of that is to say that Downs is a serious newsman, with a well-honed skill set and a deep reservoir of sources, and that he brings all of this to bear for this, his fifth and perhaps most important book. It is obviously a must-read for any Glenn Miller fan, not to mention anyone interested in the intelligence war fought in Europe between the Gestapo and OSS, which later evolved into the infamous CIA. While the music of Glenn Miller is frankly nothing I would seek out in most cases, after reading this book, I will definitely do this American Hero the honor of giving it all a thorough reappraisal.

Global Book Publishers: http://www.bookpubintl.com