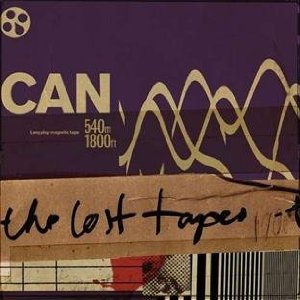

Can

The Lost Tapes

Spoon/Mute

I first heard Can when I grabbed a copy of Tago Mago, the band’s 1971 classic, while working at a CD store years ago. I had read about them in Julian Cope’s Krautrocksampler, the heralded but long out of print look at “head” music coming from Germany in the ’70s, but no amount of gushing words could prepare me for actually hearing it. From the first moments of “Paperhouse,” it was a sound completely alien to whatever I thought of as music prior. As the album played on, through the grooves and sounds of “Mushroom” and “Halleluwah” and ending with “Bring Me Coffee or Tea,” I was completely blown away from the experience. I literally thought the room was levitating.

Now, with the release of the three-CD The Lost Tapes, I might not ever come down.

When Can sold their studio in Weilerswist to the German Rock ‘n’ Pop Museum, everything was included, even down to the musty old mattresses on the walls. In a cupboard were over 50 hours of tapes of the band, covering the years 1968-1977. Can taped everything – all their shows, rehearsals, jams – and then taped over it when new tapes ran out. Later, Holger Czukay, the bassist, and Irmin Schmidt, the keyboardist, would pore over the amassed material, editing it, overdubbing found sounds, and meshing many different performances together until a song appeared. And they played constantly.

At their most potent, the band, with Michael Karoli on guitar, the indescribable Jaki Liebezeit on drums, and either Malcolm Mooney or Damo Suzuki on vocals, honed their sound by jamming, but not jamming as we normally think of it. Theirs was not the endless blues recycled or long, masturbatory solos of today’s “jam bands,” but rather an oft-times sparse sound in which each instrument plays an improvisational role for a moment, and then drops out, only to resurface minutes later in another guise. Liebezeit was a drum machine with a pulse, relentless in his intensity and dedication to the groove, but never overplaying. Schmidt had studied under Stockhausen, and he turned that unorthodox schooling toward rock music, and with Czukay, they created a sonic tapestry that refused to be shackled by convention. They were some of the first to include aural snippets amid the instruments, long before sampling was possible, and Damo Suzuki was fond of using his voice as an instrument, dispensing with normal language altogether.

When you listen to Can, you are hearing the sound of freedom, the freedom that comes from having no commercial expectations at all, playing because you want to see what you can create that didn’t exist the day before. For example, the cut “Midnight Men,” which sounds somewhat like a horror movie soundtrack (and may well be, as one of their early albums was Soundtracks, another Monster Music). The keyboards start the song in a rush, headlong down a narrowing path, drums propelling until they all fade away, only to come back as ambient washes of synthesizers, burrowing into your skull incessantly. This is the music of relentless imagination, an unburdening of the shackles of conformity and full of influences from around the world: a tribal drum beat from Africa here, a jazz flute solo there, a James Brownish bass pattern, perhaps. And in the end, it all sounded like no one else but Can. This brilliant box set, in a 10-inch tape box with copious notes from Irmin Schmidt, is out of this world.

Literally – out of this world.

Mute: http://www.mute.com