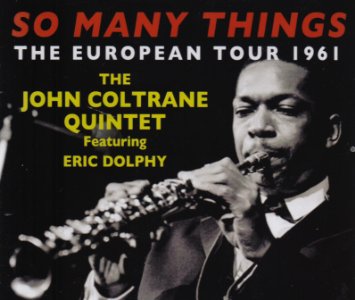

The John Coltrane Quintet featuring Eric Dolphy

So Many Things: The European Tour 1961

Acrobat

To many, John Coltrane was far more than a gifted jazz saxophonist. He was and even now remains, close to fifty years after his death, the embodiment of romanticized, aspirational notions of what jazz – and indeed improvised music as a whole – yearns and ought to be: uninhibited, unfettered, extempore self-expression as a path toward pure spiritual transcendence. His performances are both seance and meditation. His instrument takes on shades of the confessional, the censer, the prayer mat.

If that has overtones of a cult of hagiography, that’s because it is. The St. John William Coltrane African Orthodox Church, established in San Francisco in 1971, isn’t some tongue-in-cheek experiment in performance art. Even less apostolatory listeners with a few inches of critical distance aren’t immune to these mythologizing tendencies; see Tony Whyton’s insightful Beyond A Love Supreme for a marvelously pithy dissection of all the wish fulfillment to which Coltrane’s work is subject.

When it came to matters of the soul, however, Trane certainly knew a thing or two. His was a profoundly restless one. Starting with Blue Train (1957), only his second album as leader, Coltrane began making sonic leaps between albums that might have occupied other artists for their entire careers. Giant Steps (1960), My Favorite Things (1961), Impressions (1963), A Love Supreme (1965) and Ascension (1966), released in fittingly superhuman succession, are not only milestones in Coltrane’s own discography but in the history of jazz. The developments they introduced rocketed the genre through one of its most innovative but fraught periods. Although Trane would revisit more traditional – some might say retrograde – forms of playing on interstitial LPs like Coltrane (1962) and Ballads (1963), he increasingly sought to locate the ineffable somewhere among the inner technical workings of music, a kind of mathematical speaking in tongues. Or, as Simon Spillet puts it near the start of his 38 pages of downright masterful liner notes to So Many Things,

“[H]e pioneered his patented “sheets of sound”, taking both himself and his tenor saxophone to the very limits of physical capability. Cramming every bar chock-full of substitute harmonies, Coltrane’s playing had taken the hip ideal of “running the changes” to its logical, inevitable end.”

Listening to these four discs of recordings from the Coltrane Quintet’s 21-date tour across Europe in 1961, there’s definitely a feeling that we’re approaching a musical cul-de-sac. True, this isn’t what you might call late-period, “free” Coltrane by any means. These live sets were captured on tape three full years before A Love Supreme, widely regarded as the culmination of the saxophonist’s musical-spiritual quest (though Ascension and Expression (1967) strive for still higher zeniths). Yet some kind of “logical, inevitable end” does seem to be within earshot. At the time it divided audiences and critics. Longtime fans and aficionados called it “joke music,” “gobbledegook,” “extraneous noises,” “the low water mark of jazz”.

But is the reaction really so different five decades on? Sit the uninitiated down with any of these discs and odds are they’ll be drumming their fingers or pulling faces before long. Even at this accessible midpoint in his evolution, Coltrane continues to be something of an acquired taste.

Of course, it wouldn’t help the newcomer that the sound quality on So Many Things ranges from barely tolerable to barely listenable. The various concerts – four dates, six houses total – are either slushy and muted or tinny and hollow. Elvin Jones’ unrelenting cymbal crashes on the November 18, 1961 set might as well be plates dropping in the next room. The wheezy upper register (where Coltrane and his fellow reedman Eric Dolphy can spend an awful lot of time) exceeds the limits of the medium. Reggie Workman’s upright bass is virtually nonexistent. For the warbly November 22 set in Helsinki, it’s the inverse of all these issues. Some of these archival recordings appeared on the 2001 seven-disc box set Live Trane: The European Tours from Pablo Records in noticeably superior quality; why something close to the same mastering couldn’t be applied here is hard to fathom.

The fact that some of this material has trickled out in one form or another is worth reiterating, if only because it means there are already hundreds of appraisals of it already in circulation. A rough and dirty sampling reveals repeated praise for the “urgency” of these live performances. That’s something that can’t be disputed. The iconic head of “Blue Train” at the November 18 first-house show (11.18.61/I) becomes slurred as though in impatient haste; backed by Jones’ rat-a-tat, Trane starts wailing as soon as it concludes, leaning on the same note like he’s sounding an alarm. Over the course of their extended solos Dolphy and pianist McCoy Tyner follow suit, with Dolphy in particular looking like the impetuous, flamboyant protégé, virtually tripping over himself to blast through all possible permutations of every song he’s ever encountered. Not long before the 13-minute mark he quotes an amped-up “Old MacDonald.” Whether you view that as cheekily playful or brash and condescending depends, I think, on your disposition toward this material. According to Spillet’s read-along text, contemporary British audiences were not amused.

During the second-house rendition (11.18.61/II) of “Blue Train” (shorter than the first by more than three minutes, a diet that continues with successive dates), the reedmen take the same slurred notes of the head and tease them out into standalone flourishes. Unlike the earlier performance, the additions and deviations subtly telegraph more than just tempo. Trane’s ensuing solo showcases speed and intensity without forsaking all else. The result is a slightly more nuanced performance overall with a richer, more satisfying emotional palette. There’s something to be said for urgency, to be sure; yet urgency, like so much else, is relative, and it’s augmented through shading and contrast. For that reason the high points of So Many Things aren’t necessarily the furious maelstroms where the brass honks and shrieks until hoarse, but rather the moments in which the quintet dials things back from 11.

Regardless of the set, “I Want to Talk About You” (So Many Things has three version to choose from: 11.18.61/I & II; 11.22.61/II) shows Coltrane’s skill as a balladeer. Though he and Tyner are the only ones to solo, these tender, often poignant performances dispel any reactionary notion that the leader and his band in any way lacked complete command over their craft. That goes doubly for “My Favorite Things,” the catchy waltz-time Rodgers and Hammerstein tune from The Sound of Music that Coltrane turned into a modal deconstruction and made his own. There are six versions here (1.18.61/I & II; 11.20.61; 11.22.61/II; 11.23.61/I & II), some reaching close to half an hour. These live versions are unhurried explorations of the central melody from every angle, like walking through an exploded model of an engine and its component parts. Following the intro, Trane is relatively quick to give way to Tyner, whose long solos give the listener ample time to fall under the hypnotic spell of his left-hand vamp. For those only familiar with the studio version, Dolphy’s virtuoso flute on the November 20, 22 and 23 sets makes for interesting variants.

As Spillet’s postscript notes, Dolphy’s departure from the group the following spring left the basic framework for the “classic” quartet, namely, Trane, Tyner, Jones and Jimmy Garrison (replacing Workman). This is the legendary outfit that would go on to create A Love Supreme and release six albums on the Impulse! label in 1965 alone. Had Dolphy and his polarizing presence kept the group operating as a quintet, it’s hard to say if it would still be held in such universally high regard. But that’s all speculation. However apprehensively audiences might have greeted to these live performances in the past, however they might react to these subpar recordings of them now or in the future, one thing’s for sure: Coltrane devotees need not worry. The canonization of St. John is long since complete.