Remembering WWI’s Bloodiest Battles

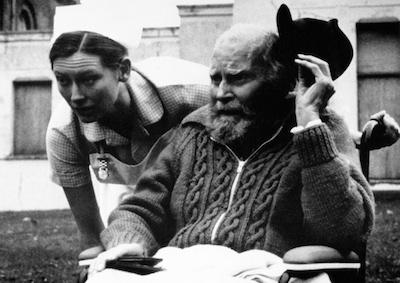

an interview with Jan-Christopher Horak, director of the UCLA Film and Television Archive

by Generoso Fierro and Lily Fierro

Today, being Veterans Day, I am reminded of the stories my father told me about his time when he served as Bersaglieri in World War II and of the multitude of combat veterans in the neighborhood who told similar stories, even though they had just returned from Vietnam. I read Erich Maria Remarque’s novel, All Quiet On The Western Front, at a very young age, and it left a lasting impression on me, and shortly afterwards, Sister Anne, one of the teacher nuns in my parochial elementary school showed us the 1979 Delbert Mann directed version of the novel, which, despite being made for American television, was extremely graphic, well-acted, and had the spirit of the book and Remarque’s anti-war message. Since then, I have intensely studied World War I and have often referred to it as the most obscene war in human history, not only because of the reasoning behind the need for the conflict but also the way that the combat had been carried out in terms of new killing technology meeting older fighting strategies.

On November 18th, 2016, the UCLA Film and Television Archive begins its series, Remembering WWI’s Bloodiest Battles, which runs through December 11th. The series features many rarely seen films from different eras and nations that center around the most brutal year of the war, 1916, which saw the horrific battles of Verdun and the Somme. I recently sat down with Jan-Christopher Horak, the director of the Archive, and the programmer of this series to discuss his programming decisions.

• •

Given that 1914 was the official beginning of World War I, could you speak about 1916 and the importance of that year as the year of inspiration for your program, Remembering WWI’s Bloodiest Battles?

Well, we didn’t program anything about the war in 2014. A lot of our colleagues actually did World War I series that year; the International Federation of Film Archives at our yearly conference, which took place that year in Skopje, held the festival in the same area around where the battles occurred. Somehow I wanted to memorialize World War I during the four years of its anniversary, so, for the one hundredth anniversary of 1916, which was the most terrible year of the war given the incredible losses, I curated this program. Also, I had also read Arnold Zweig’s book, Education at Verdun, which I read in the original German, since I completed my Ph.D. in German, and that novel impressed me greatly. At first I just wanted to screen films about the battles of the Somme and Verdun, but there are not that many fiction films about those battles to make a full program, and so I had to cheat a little; a few of the films are not about 1916 specifically, but this was a good opportunity to do a series about World War I.

World War I, more than almost any other conflict that the U.S. has been involved in, seemed to become more ghastly due to the rapid development and untested use of new killing technology… tanks, machine guns, poison gas, air combat, both against other planes and ground troops. What becomes the true ugliness in my eyes is that some combat strategies, such as walking in formation, historically in place because they were effective against older weapons, were still being used against new technologies that made these methods completely futile. Is it for this specific reason that you have avoided any films that romanticise the war?

Yes, it is, and that is why I didn’t want to include some of the Hollywood films, some of which were either romances or comedies that trivialized the war and were very popular at the time.

I understand that there are some comedic elements that Universal forcefully added to James Whale’s 1937 film version of The Road Back, Erich Maria Remarque’s sequel to All Quiet On The Western Front, after the Nazi Consulate in Los Angeles threatened to boycott all Universal films coming into Germany due to the negative light cast onto Germans with Whale’s adaptation. It was also severely edited as well. UCLA will be showing a restored version of The Road Back in the series, but how much of Whale’s original vision is intact with that version?

The version that we will show is Whale’s first cut. It is the version that Universal didn’t release. Whale had finished the film, and then he was taken off of the project, so when the film was released originally, scenes that he shot with Slim Summerville and some of the more critical scenes of Germany were taken out. These have now been put back into this version, which may not be the final version, as it has been eighty years since its creation, so we cannot be absolutely sure that this was his exact version. Actually, the negative of the film was in our vaults, and that is how Universal created this restored version, which again maybe is not one hundred percent of Whale’s vision, but it is much closer than the originally released version. For example, with the new version there are many scenes that depict how badly soldiers were treated when they returned from the war. This new version also contains scenes where you see how the right wingers have taken over, which is a direct commentary on Hitler on fascism.

Was Whale’s The Road Back the only Hollywood film that used World War I to warn people about Germany’s rise to power before the beginning of World War II?

No, there were others, including the first film in our series, Ernst Lubitsch’s 1932 film, A Broken Lullaby, which is about a French soldier who goes to Germany to meet the parents of a German soldier whom he has killed to ask for forgiveness, but he is treated badly by the townspeople there as the wounds of the war had not healed. It is also a critical film about Germany, and because it was so critical, it was a box office failure, and for that reason so many people have never heard of A Broken Lullaby, even though it is Lubitsch.

Was A Broken Lullaby, perhaps because of Lubitsch’s prominence in Hollywood, not tampered with in terms of forced edits?

We do have to remember that The Road Back is also an adaptation of Remarque’s novel sequel to All Quiet On The Western Front. And, when The Road Back was filmed, the States were more volatile than they had been in the year that A Broken Lullaby was released.

I have read both Remarque books, so I guess that the timing of Whale’s production of The Road Back was more the issue?

It is interesting because starting in 1935 to 1936, there was a significant war hysteria happening here. G.W. Pabst, who was in Hollywood and had already made one film, was working on an anti-war movie script in 1935 that takes place on an ocean liner when the war breaks out, and there are people from opposing nationalities on the ship, and that forms the drama, but the film never got made. When I was doing research on Pabst, I discovered that there was a good deal of hysteria, especially in Europe, but also in the United States that I found in newspapers from that time about another war coming. And as far as the German Consulate was concerned, they worked very hard in trying to influence Hollywood, and they succeeded. F. Scott Fitzgerald was also working on a film at MGM about Germany that also got shut down around this time. In 1939, Warner Brothers made Confessions of a Nazi Spy, and the German consul showed up at the studio and threatened them. By 1936, Warner Brothers had already pulled out of Germany when one of their heads of distribution, Philip Kaufman, was beaten to death by SA men on the streets in Berlin. MGM, even after 1940, was still trying to distribute films in Germany and was periodically removing Jewish names from the credits so that the movies could be screened there. For Hollywood, money was always more important than ideology.

Speaking of that era, Dalton Trumbo, already a successful screenwriter in Hollywood, wrote his novel Johnny Got His Gun in 1939, but he doesn’t make the film until 1971. Did any of the pressure from the German Consulate come into play in keeping him from adapting his novel for the screen?

Well, I think that has more to do with the fact the World War II happened. World War II for us in a sense, is a “good war” because we were fighting fascism, so even though he published Johnny Got His Gun in 1939, Dalton Trumbo was also writing scripts for anti-Nazi films and pro-war films. So, during the war, Trumbo is gainfully employed, but then immediately after peace is declared, he is blacklisted and cannot work for years and years except under a pseudonym or through fronts. You also have to take into consideration that the ’40s and ’50s were not a good time to make anti-war films, as it was the Eisenhower and anti-communism era that caused purges in Hollywood. I think that when Johnny Got His Gun finally got made, it was the first time that it could’ve gotten made. Sure, there were a few anti-war films made in the United States before Johnny Got His Gun, but not significantly before that, so once he made the film it was perceived more as one about Vietnam given the time when it was released.

Considering how honest but grim Johnny Got His Gun is, I was surprised to find out how successful it was at the box office upon its release. I believe the film was produced for only $80,000 and did well enough to make that money back and then some, but then the film sort of disappeared.

I’ll tell you, we had a really hard time finding a print to show as part of this series, but I am glad that we did.

William Wellman’s Wings is the first film to win Best Picture at the Academy Awards, and Howard Hughes’ Hell’s Angels becomes hugely successful at romanticising what really was a very ugly war. It seems that going from those films to present day films about war such as Flyboys, whenever Hollywood wants to romanticize a war, they do it through air combat. They seem to desperately avoid ground combat because it is difficult to make any aspect of that style of warfare seem remotely acceptable. As far as World War I was concerned, do you think that the decision to make so many aerial combat films was more because of a jingoistic agenda, or was it because of the opportunity to depict this new type of action cinematically?

I think that there is something to what you are saying, as there are films that have some ground combat like King Vidor’s The Big Parade and John Ford’s What Price Glory, but both of those films basically are more about soldiers behind the front than in the trenches during battle. This is pure speculation, but someone like William Wellman, who was one of the first Americans to join the N.87 escadrille in the Lafayette Flying Corps as a fighter pilot, or Howard Hughes, who was an aviator as well, may have felt that air combat was something modern, and so their goal was not only to depict the war but also to depict the beauty of flight, which gave the growing aviation industry a boost as well, and since Hughes had his own aviation company, these films also worked as advertising. Also, usually when a pilot is shot down in one of these films, it gets noticed by the other pilots when he doesn’t return to the ground with the rest of the squad. His death then appears to be even more epic because a ground soldier, with few exceptions, is seen as part of a company, so his death, though tragic, often appears to be as part of a strategy or fate, whereas the fighter pilot is like a cowboy; he is alone, but his fate seems more determined by his skill.

For my final question, I have to bring up Derek Jarman’s 1989 film, War Requiem. My wife and I love Jarman, and I am astonished that you found a 35mm print for this program as I do not believe that I have ever seen this screened.

I was thinking about Jarman just the other day as I was at Telluride when his film, Blue, premiered just a few months before his passing. It is hard to believe that he died over twenty years ago. I wanted to make the program a little unconventional. I wanted to show a variety of aesthetic strategies for dealing with war as I am sure that you have read Paul Virilio’s book, War and Cinema, because this is the conundrum for filmmakers: how to depict war without turning it into a visual spectacle, and this is indeed the point of Jarman’s film, to deny you that visual spectacle.

And then you have programmed Richard Attenborough’s 1969 film, Oh! What a Lovely War, which is almost the antithesis of what Jarman is doing with War Requiem.

It is cabaret. Jarman may have been a lot of things, but he did not have a strong sense of irony, whereas Attenborough does, and I also wanted to screen it because, truthfully, I haven’t seen it screened in such a long time, and I wanted to have participants from various nations well represented in the program. That is why I also included Francesco Rosi’s Many Wars Ago and the Attenborough film as I wanted another strong English film.

• •

Thank you to Jan-Christopher Horak for taking the time to sit down with me for this interview and special thanks to Kelly Graml, the Marketing and Communications Manager at the UCLA Film and Television Archive, for all of her assistance in helping to make this conversation happen. ◼

Remembering WWI’s Bloodiest Battles: https://www.cinema.ucla.edu/events/2016/remembering-wwi-bloodiest-battles