Director Philip Kaufman Revisits The Great Northfield Minnesota Raid

by Generoso Fierro

Like so many, I was deeply saddened when I heard the news that Sam Shepard passed on July 27th of this year. Shepard possessed such eclectic talents as a both a writer and an actor, but yet, with all of his significant contributions that he provided us with, I must admit that the first aspect of Shepard that I thought of when I heard the news was his dynamic portrayal of famed Air Force test pilot, Chuck Yeager, in director Philip Kaufman’s exhilarating 1983 film, The Right Stuff. For me, that film was a perfect storm; at the time of its release, I was fourteen years old, the perfect age to see it I feel, and I had been given the Tom Wolfe novel from a family friend who loved all things space a year or so prior, so I was super excited to see the film, and finally, whether I knew it or not, I had been loving Philip Kaufman’s films for years without even knowing that Kaufman had directed them.

Similar to Sam Shepard’s, Kaufman’s output was indeed quite eclectic by the time he had directed The Right Stuff. All you need to do is simply look at Kaufman’s output from 1978 to 1981. The director’s 1978 feature, Invasion Of The Body Snatchers is universally celebrated as the finest adaptation of Jack Finney’s classic science fiction novel. The very next year Kaufman smartly adapted The Wanderers, Richard Price’s gritty novel about racially divided street gangs in 1960s Brooklyn, and then in 1981, the homage to the serial films of the 1930s that Kaufman had co-authored with George Lucas years earlier became Raiders Of The Lost Ark. Be assured though, in the years after I saw The Right Stuff, I became quite fascinated with Kaufman and how he was able to effectively vacillate between so many genres as a director.

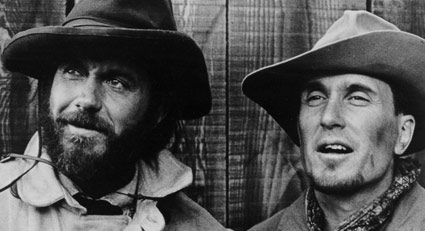

Recently, I was fortunate to have the opportunity to hear Philip Kaufman speak in person with former New York Times film critic Stephen Farber about not only Kaufman’s overall career, but also the evening’s film, Kaufman’s seldom screened or discussed 1972 revisionist western, The Great Northfield Minnesota Raid. When we speak of the American revisionist westerns of the late 1960s and early 1970s, the conversation naturally turns to films such as Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch, Arthur Penn’s Little Big Man, and Altman’s McCabe and Mrs. Miller, but I have always wondered: why had Kaufman’s 1972 brazenly irreverent look at the last robbery perpetrated by the infamous James-Younger gang been so overlooked both critically and financially at the time of its release and since? It is a fact that westerns, in general, had not been as lucrative by 1972 as they were in the early 1960s in the United States, but surely a film starring the recent Oscar winning actor Cliff Robertson (for 1968’s Charly) and Robert Duvall, who was starring in the most popular film of that year, The Godfather, would have piqued audiences’ desires to see those actors in a new film, no matter what the genre? Was it then the critics, who wielded immense power in that period, the culprits for the failure of The Great Northfield Minnesota Raid to find an audience?

In May of 1972, Vincent Canby of the New York Times and Jay Cocks of Time magazine had written somewhat mixed, but mostly positive reviews of Kaufman’s western, and Richard Schickel for Life magazine on June 16, 1972 wrote:

“The film has about it a wonderfully fresh air. Scenes that begin conventionally enough twist off into unexpectedly humorous or brutal paths, characters that seem familiar enough at first glance develop odd wrinkles. Even scenery and decor that we’ve all seen too many times is glimpsed in a new light, from new angles.”

These reviews were not by any means overwhelmingly strong endorsements, and there were also some purely negative reviews, but as Stephen Farber, who was an early advocate of the film, would soon find out, “Universal Studios was trying to bury the film” (Film Comment, Jan/Feb 1979).

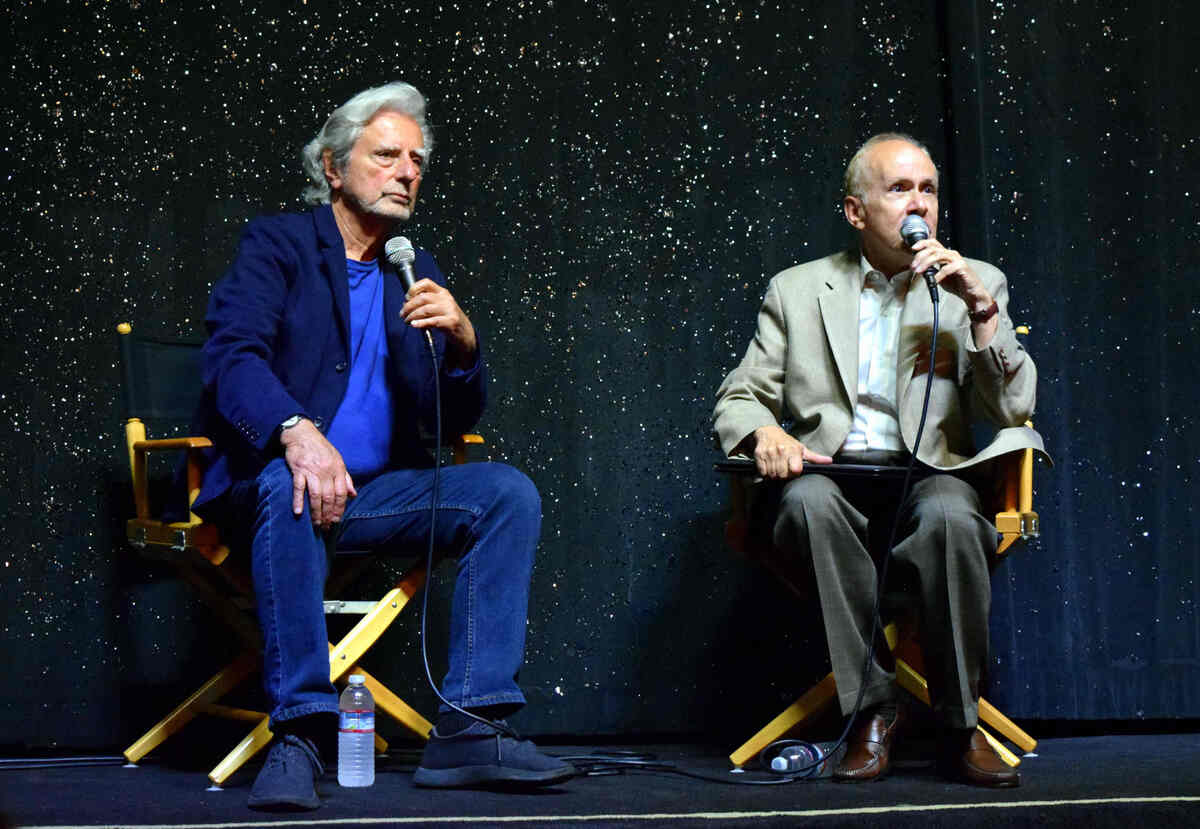

The following is a transcript of the onstage conversation between Philip Kaufman and Stephen Farber that occurred at the Ahyra Fine Arts Theater in Beverly Hills on August 18th, 2017.

Q: Stephen Farber: Thank you. I am glad that for our opening tonight of this year’s Western Weekend at the Ahyra Fine Arts, that we can introduce you to a film that is not as well known as some of the others that are being seen this weekend. So, without further adieu, I would like to introduce the writer and director of The Great Northfield Minnesota Raid, Philip Kaufman (applause). So, tell us Philip, I know that you are a bit of a history buff, what got you interested in telling this story, the grittier truth of the history of Cole Younger and Jesse James?

A: Philip Kaufman: So, I don’t know about being a history buff, but I was doing my postgraduate work in history at the University of Chicago, and I just felt history wasn’t connecting with me, and I wasn’t connecting with history because it was something frozen and academic. I had been through different places like Harvard Law School, and I had decided that there was no vitality and no dynamism to what I was studying. There were a lot of a opinions and a lot of memorization of facts, but there was no vitality, so if I became a buff it was because I was reading stuff that wasn’t in the history books – it was in the chronicles often of different outlaws.

As for Jesse James, I had done a couple of very low budget independent films in Chicago that didn’t take off, but you have to remember that, when I started, there were only a few independent directors. There was of course, Cassavetes and Shirley Clarke, and a few others when [Benjamin] Manaster and I did a film called, Goldstein (applause). Goldstein went to Cannes and won a Critics’ Prize [Prix de la Nouvelle Critique]. We had also done Frank’s Greatest Adventure, which the distributor later called, Fearless Frank, which we had done with amongst others, Severn Darden and many Second City people, but these films didn’t give me the ability to raise money in Chicago, so we packed up and moved to San Francisco during the Summer of Love and then came down to Los Angeles, and I got a job at Universal where I eventually was making a hundred and seventy five dollars a week and entered a young filmmakers program. During that time, I ran into Frank Price, who later would run a couple of studios here, and he and I became friends, and so we started talking about Jesse James and for a while he helped me shape this project.

I wrote the script for this film four years before it was made. By that time, there were all of these Jesse James movies out, and he was sort of this iconic, heroic figure, much like those whom I was reading about in graduate school, but that wasn’t the history that I had found. No, he was something of an egomaniacal, sadistic character, a blinky-eyed bastard in some ways, but fun and interesting in his own way! But as you’ll see in the film, the main guy in the James-Younger gang was in fact Cole Younger. Jesse James, after Younger’s capture, went on to create the legend that many understood. So, when I did the film, people were calling it an alternative history because my friends who were in the movement, the more radical of the bunch, said to me, “Don’t touch fucking Jesse James because he was a hero!” I mean this guy was a racist, but people come to create heroes in strange ways, and I see now that the reason why we are having all of the problems of today’s world is that we created heroes without balance really, comicbook heroes we can say. And I thought, can we approach history and the James-Younger gang by bringing in historical facts while having some of the fun and stupidity of history and some of the pulp qualities of films? By this I mean that the film is called The Great Northfield Minnesota Raid, and it wasn’t great at all. And as you’ll see in my film, both sides claimed to have written the history of it in one way or another, and both sides had reason to be perhaps ashamed of the history that they had passed down through time.

So, I wanted to do something that was alive and fun, and I guess that maybe my background from Chicago and Second City led me to approach history in that way. Sometimes, it is truer if you can laugh at something. Sometimes Saturday Night Live can get to the truth about a president in a more effective way than the evening newscast for example. So, there are these elements of all of this here as you watch the film, and it was made in the way that I feel that all films should be made, which is that it was made by people who wake up in the morning and who care about the tasks that they are totally involved in and who feel that they are doing the most important thing in the world, no matter how funny or strange. We just wanted to strip away the cloak of Hollywood from the film.

Q: Had you been a fan of other westerns? I mean this had been an era of the revisionist approach to the western genre with Peckinpah and Altman.

A: Well, this had been shot at the same time as McCabe and Mrs. Miller, and for various reasons, its release had been put off, and I could go into why it was put off, but I loved Ride the High Country, which you are also showing this weekend here, and I think that the films of that time and the filmmakers of the late ’60s and early ’70s were all trying to present things the way they might have actually been, with characters who may have actually lived in that time as opposed to the characters in westerns from the 1950s who looked like their hair had just been cut and always had a clean shirt in every scene and who were acting a plot rather than acting and immersing and submerging themselves into the character. You’ll see in this film a young actor who had done a couple of features prior to this one named Robert Duvall, who when I think of his portrayal of Jesse James here, I think that you are seeing one of his greatest performances.

Q: How did you come to cast Duvall? I too feel that he brought a very fresh approach to his character in this genre.

A: I had just met him in interviews. I didn’t know Francis [Ford Coppola] that well, but they had done The Rain People prior to that, but he was Boo Radley and performed in a few others things, and we hit it off. He is the kind of actor that I have the most admiration for. There is a scene, for example, in this film where he and some of the other members of the gang come riding into Northfield on four horses abreast, and they come riding around the corner in a heavy rain. This was Oregon, and we began shooting the movie for various reasons after Thanksgiving when it would be dark by three in the afternoon and raining every day. It was very tough and the whole movie was shot in maybe twenty eight days.

In this scene, I was on the roof with my cameraman, Bruce Surtees, who was a marvelous cameraman (applause), and he was on a box, and I had a headset on next to him, and we hadn’t done any rehearsals, so when the horses came around the corner and I heard, over the remote, Robert Duvall saying these lines, “Here she is Frank, the City of the Plains,” I suddenly, because I had spent years thinking about this, thought that his voice was the voice that I had in my mind when I was writing this. So, I unintentionally grabbed his [Surtees] legs, and I don’t know if the camera shook, but it was one of those great things that a director could have had happen to them. I have had that happen a few times with some great actors that I have worked with, where rather than telling them what to do, I became an audience for them. There have been occasions in my career when I have been so enthralled by what the actors were doing that I forgot to say “cut.” There is some incredible talent of certain actors, and it doesn’t get the play that it should, or even the recognition from critics, so when you see Duvall here people should feel this performance.

Q: Duvall’s co-star, Cliff Robertson, was more in the older tradition, yes?

A: Yes, Cliff was a little more old school. A very good actor, he had just won an Oscar for Charly, and he approached the film differently, more from the Hollywood style, but he really wanted to do the movie, which was great considering he won had just won the Oscar, so kudos to him for being part of this.

Q: You are a big fan of ensemble in a lot of your films, and you have a lot of fine actors in this film in small parts. Is that important to you to get these small parts filled with the right actors to add texture?

A: When you’re cooking the stew, you want all of the flavors to come through. Too often in American movies, and even American theater, peripheral characters fall off because everything is centered around the star. This is not as much the case in British theater, where every person has a developed character. I remember when we did Invasion of the Body Snatchers, and Donald Sutherland was having some small problems with a scene, so we shut the set down, and we were then all sitting down talking about it when Brooke Adams, Leonard Nimoy, and a bunch of the actors started saying, “Donald, we know what we are going to do, so any choice that you make…” You knew they were fully aware of their characters, so they were capable like a great team saying, “Pass the ball to us; we’re not going to respond to this in a stiff way.” The great actors do that. You know I have worked with so many, Geoffrey Rush, Daniel Day Lewis, Clive Owen, Nicole Kidman, it is incredible as to how receptive they are. There is a kind of brilliance, a kind of zen truth when they are there in that moment, and you only can hope that the camera is getting all of those things. I hope that Caleb Deschanel, one of the world’s greatest cameramen who is here tonight (applause), understands that they are making the film with you. The actors, the cameramen, they are collaborators, and they are all making the film too.

This weekend, you are showing films by great directors, Sam Peckinpah and so forth, but to me sometimes the greatest films are the ones where the audience is just part of the scene if they can get carried away by a performance, by lighting in the film, and that’s why you move the camera in a certain way, why you edit it a certain way, and this is to not seduce them for commercial reasons, it is to tell a tale, and if the writer and director feel that it is an important tale, then the actors are there to cook it.

Q: Going back to the historical elements of the film, I just wanted people to notice all of the visual details in this movie that bring the past to life here. The little touches and the sets and all of the care that was put into that which brings such a great texture to the movie.

A: Now, people do that level of texture much more these days. It is something that set designers are more conscious of when they make a film today. Back then, it wasn’t so much a priority, the small details. They shot backlots, and there was a certain artificiality that people accepted. That shirt that John Wayne would wear was maybe a color that really didn’t exist back then, but it didn’t matter. Even when we were framing this film, we looked at old photographs, and they were often off center; they were skewed, awkward even, so we tried to create that feeling that we were seeing in the photographs, but some critics came back and wrote that “Kaufman doesn’t even know how to frame a shot.” So, I felt that there was a certain awkwardness to some of the film here that I hoped and felt was historically true.

Q: A number of your films have been set in the past, different periods of history, and so I have always wondered if you have a little bit of a distance from the present and have always had a kind of attraction to other periods of time?

A: The past is something that I can know something about. Too many people are busy predicting the future without understanding the past. Maybe because I started studying history, I just appreciated discovering things that I didn’t know. I hate to sound selfish, but the reason that I don’t make the same film over and over or try to just do a genre film is because, if I have already done something, then I selfishly want to learn something else. As for The Great Northfield Minnesota Raid, after we had completed it, I could’ve done more westerns. After Unbearable Lightness of Being or Henry and June, I could’ve just had more sex! (laughter) It is an adventure. When I saw this film the other night, you’ll see as a part of Cliff Robertson’s character, the ethos of, “No matter how many times you get shot down, you have to keep on getting up,” and now fifty years later, I appreciate that, and I sort of think that Cole Younger’s story is sort of mine.

Q: Well, I want to thank Philip (applause)…

A: No wait, I have one more thing to say…So, this film was rushed into release for various reasons, and there is a number of stories I could tell, like we had a temp track of Bob Dylan’s “Nashville Skyline,” and the studio told us to get “that fucking music out of there,” and then Dave Grusin did a great score for us, but then the film came out, and a number of the critics didn’t like it, and sometimes critics respond to the shabby release of a film, but this was my first Hollywood film. So, I got under the covers, and I told Rose, “That’s it, and maybe I’ll go back to being a mailman or a Fuller Brush man.” I mean, I was a good mailman once, but at that moment, I was under the covers, and the phone rang, and Rose said, “Stephen Farber is on the phone.” I knew that you were writing for the New York Times, and so then, I sort of reached out from under the covers, and it was you, Stephen, and you said, “ I saw your movie, and I loved it,” and well, here we are!

Q: Let me just say that I went to see the movie at Universal at a press screening, and I didn’t know anything about it. I hadn’t gotten any advanced publicity, but I had heard of the actors, and I thought that it would be interesting, and it was a total discovery for me! I just felt, my God, what are they doing? This is one of the most original, engaging, and funny approaches to the genre, and so yeah, I felt the need to call you and tell you that I thought that because I felt that the film was not getting its due. It is nice to discover a movie that you don’t know anything about; you go in without any expectations, and you’re sort of pleasantly surprised, and that is a great experience to have. This level of surprise is somewhat lost now, of course, because we have so much hype, sometimes false hype, surrounding a release.

A: Thank you Steve, and that is why we need critics. Thank you so much. ◼