Jonas Carpignano

by Generoso and Lily Fierro

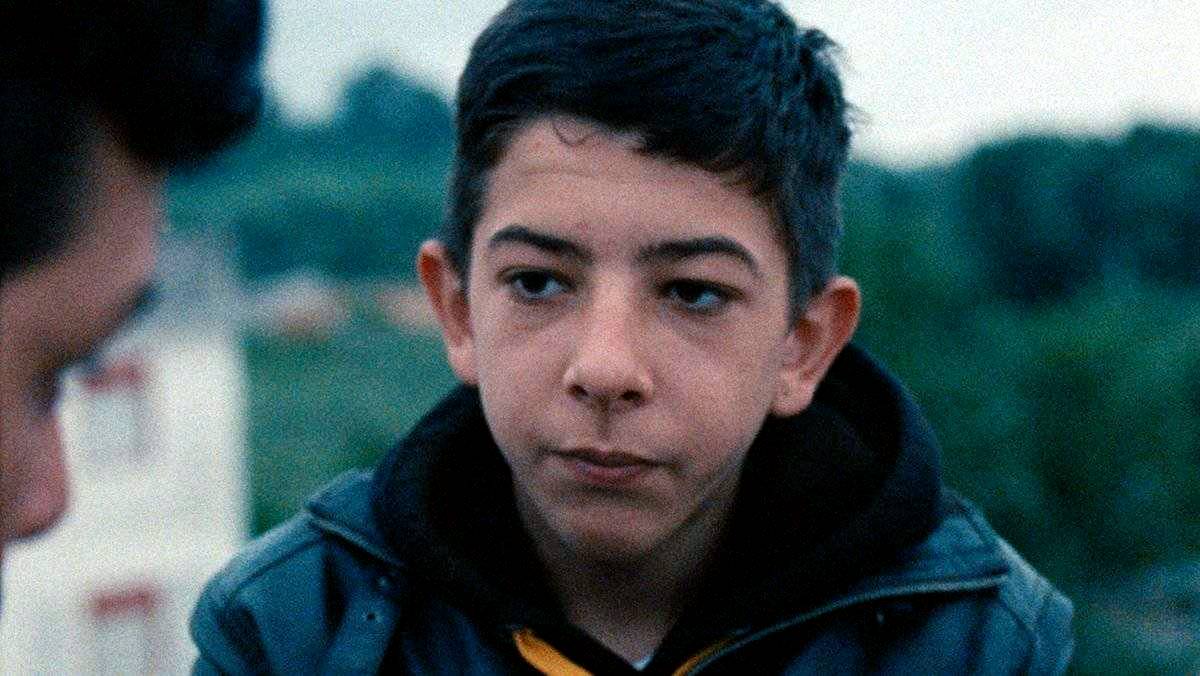

It has been two years since we last saw Ayiva (Koudous Seihon), the African refugee from Burkina Faso who settled in the Calabrian port town of Gioia Tauro and who is the protagonist of director Jonas Carpignano’s much heralded debut feature, Mediterranea. What distinguished Mediterranea was its intimacy with Ayiva’s experience as a newly arrived immigrant, and this intimacy is continued in Carpignano’s second feature, A Ciambra, but with Pio (Pio Amato), a Romani boy, now teenager, whom Ayiva sporadically encountered in Mediterranea. As a resident of Gioia Tauro himself these last six years, Carpignano has a rare and honest understanding of his surroundings and the perspectives of the people who live in it, which enable him to create film experiences that are true to his fellow residents while being reflective of his own process of assimilating into the community.

Originally a peddler of small stolen goods in Mediterranea, Pio, in A Ciambra, has ambitions to follow in the footsteps of his older brother Cosimo (Damiano Amato), who subsists in the underground economy, the only economy that is accessible to the Romanis that offers any ability to ascend out of poverty. When a desperate need for Pio to contribute more to his family emerges, Pio develops a friendship and also somewhat of a partnership with Ayiva that draws into question Pio’s allegiances to his own family. As was the case with Mediterranea, A Ciambra is fervently committed to its central figure, Pio, and as a result, the film serves as the astute second installment of a triptych of character-driven films that aim to form a comprehensive examination of the town that Ayiva, Pio, and Carpignano call home.

We sat down with Jonas Carpignano during AFI Fest this past November and spoke at length about how his experiences with the people of Gioia Tauro shaped his approach to telling their stories.

Q: Lily Fierro: We recently watched Ettore Scola’s Brutti, Sporchi e Cattivi, which focuses on a Romani family living outside of Rome and is also a really fine example of Italian grotesque cinema, a genre which also includes films such as Lina Wertmüller’s Love and Anarchy and Marco Ferreri’s Le Grande Bouffe. We think that a lot of people who see your film will probably connect it to either crime or neorealist genres, but, for us, we see your film, A Ciambra, as almost an update and a modernization of the Italian grotesque, mostly because it is completely unrelenting, which is a key feature of the grotesque. Even though the films that I mentioned somewhat play on comedy and yours does not, could you talk about your approach to making everything unrelenting, and in turn, perhaps updating and extending the grotesque?

A: Carpignano: I think that the major distinction to make, even though I love all of those films, is that you feel that those films look to contextualize those communities and those people within Italian society, and that is why I feel that those films come off as slightly comic, or completely comic, so to say. There is certainly a way of dealing with a real situation through humor, which is common in the tradition of comedy. I think that the major difference and the reason why people tend to connect my film more to the neorealist movement is that there is an idea, or better put, a desire here to make the protagonist of the subject matter also the protagonist of the film.

The goal of both Mediterranea and A Ciambra, and what was very important to me, was to show underrepresented communities, but through their actual experiences and not the way Italians experience these underrepresented communities. There is no let up. There is no moment to step back and say, “But this is the context that they live in.” This is their life from their perspective, and if it is not important to them, then it is not going to be important to us either. One of the things that people always harp on is, “Where are the Italians in these films?” and they always say to me, “Where is the port? Gioia Tauro is a major port town, so where is it?” For me, it is not important to show that because it is not important to the protagonist of the film. In Mediterranea, people always ask, “There is a mafia presence there. Why don’t you show that?” Well, if something is not important to Ayiva, who has just gotten off a boat, who is literally just looking for his next meal, and who is literally just looking for a way to bring his family over, then you will not see it. So, if the mafia is not going to be important to him, it is not going to be important to the film. It is the same thing with Pio. People always ask, “Where are the beaches in this town?” I’ll tell them, “Well, Pio never goes to the beach because Pio doesn’t swim.” So, if it is not going to be important to him, I don’t feel the need to stop and say, “This is his life, and also this is his context.” And I think that this is why my film feels so unrelenting, so to say, because they are systematically and dogmatically married to the perspectives of the people who are the protagonists of the films.

Q: Generoso Fierro: We can understand your exclusion of showing the mafia in the film as you have no need to contextualize things that your protagonists do not encounter as part of their experiences. However, that is not to say that Pio’s experiences and interactions are entirely insular to his own Romani community. A Ciambra captures Pio’s interactions with many people, and from them, we get a sense of the social structure that Pio sees and must learn to navigate. In one particular scene, where Pio almost gets run over by a car, and in the car we see a mirror with cocaine, you expose the different kinds of criminality that occur between the groups that Pio encounters. With the “Italians,” the criminality is seen through protection and strong-arming. With the Africans and Romani, their crimes are mostly petty ones and auto theft, yet with none of these groups do we see drug trafficking. Is your omission of narcotics sales a statement on these two groups’ limited powers of organized crime? Or, did you simply not experience that form of crime in these communities?

A: Carpignano: It gives me immense amounts of pleasure and satisfaction when people draw these conclusions based on these small details because, in my own life in Gioia Tauro, I have to figure things out like that through small observations. I made a similar reflection a few years ago when I realized that no one here (in the Romani community) is dealing drugs, and no one in the African community is dealing drugs. And then one day, just like you see in my film, a car rolled up like that, and I remember Pio’s mom telling me to hide because those people were drugged up, and they were people from the “Italian” community, and that’s how I sort of managed to put it together. If you are going to be dealing drugs in that community, or in that society, you need to be in a different place in the social hierarchy than the Gypsies and the Africans, and the more I did research, the more I realized that that was true. There is a very strict hierarchy that the film tries to lay out, but not didactically, because I hope that the audience can piece it together through these little details—like I had to in my own experiences—so the fact that you did, brings me so much pleasure. Also, when we were first putting that scene together, my colorist said, “I don’t think that people can see the cocaine.” So, we put a little window on it, and we changed the shading and placed a mirror underneath—I wanted to make sure that it “popped.”

Q: Lily: As you mentioned in the discussion after the AFI Fest screening of A Ciambra, you are creating a triptych of Gioia Tauro. You started with Ayiva’s story in Mediterranea, and Ayiva continues his thread into A Ciambra, but did you write something that details Ayiva’s progression in between the two films? What are we to assume about Ayiva’s integration into this world in the time period between Mediterranea and A Ciambra?

A: Carpignano: I didn’t write it, but it was something that sort of wrote itself just because I live with him (Koudous Seihon). I have seen the difference in his, and I don’t want to say “status,” but position in that community. Whereas in the beginning he was just someone who picked oranges, years later, he has become someone who can move in a different way around Gioia Tauro because of his charisma and because he has been living there for so long. So, I have been able to see what should happen to Ayiva through what has been happening to Koudous and to many people as they sort of try to move into the underground economy. Obviously, there is no place for them in the actual economy; no one is going to give them jobs as we’ve seen in Mediterranea, so where do you go when you are sick of picking oranges? What is that next step? And naturally, that next step is participating in a kind of commerce that is somewhat underground in background. And, where are those relationships where a commerce role can exist for Ayiva? Obviously, they are between the gypsy and African communities, and not necessarily where the other communities exist in the town. How I see what happened to Ayiva between his arrival and now, is in some way, parallel to what happened between Pio’s grandfather and his family in the years since they settled and became part of Gioia Tauro. That process of becoming sedentary, of deciding that you are going to stay and live in a specific place, changes your occupations and your possibilities within this underground economy.

Q: Generoso: In regards to the underground economy, there is a particular scene in A Ciambra that suggests that, at least in Gioia Tauro, the Italians and the Romani might be growing closer by how the two groups set themselves apart from the newly arrived African immigrants. The scene we are thinking of here is when Pio’s older brother Cosimo (Damiano Amato) returns from prison and tells his younger brother about how the Romani and Italians joined forces in jail and distanced themselves from the African inmates.

A: Carpignano: I think that very rarely, when a new kid comes in, the last new kid says, “Let me help you make your life easier here.” Faced with the option of helping the new kid, the last new kid most likely will make a jump to be with the group that was there before them, and I think that is what happens here. There is now a sort of lower rung on the ladder, which inadvertently brings us closer to where we want to be, which is to this more established community. They are basically saying, “We may be Gypsies, and they may be Italians, but we are definitely more Italian than the Africans, and this place is more ours than theirs.”

Q: Generoso: You in fact have a scene in Mediterranea, which is what brought up our comparison to the Ettore Scola film that we mentioned earlier, where Ayiva begins to experience the harshness of the conflict against him and his fellow African immigrants, so he responds to a rat that enters his room by stomping it to death. It seems to suggest that we have a natural inclination to step on someone in a lesser position to gain some sense of control?

A: Carpignano: Wow, do you two read my emails? You just say a lot of the things that we talked about as we made the film that no one has ever written into an article. I am feeling so weird right now (laughs). Yes, that scene of Ayiva stomping on the rat is a statement that says: “This is the thing that is invading my space. This is the thing that is reminding me of where I am, so if I could kill that thing or distance myself from that thing…” This is a moment where his frustration can come out.

Q: Generoso: Thinking now about that change from being nomadic to sedentary, which is an essential theme in A Ciambra, you show this shift with a motif of citrus fruits (oranges and lemons) in both Mediterranea and A Ciambra. In Mediterranea, we paid close attention to how Ayiva eats the oranges that he picks. At first, he doesn’t eat them, but by the middle of the film, we see him beginning to eat the oranges, but he does so by only peeling away a small percentage of the orange peel and eating, as if he is slowly uncovering the community where he lives. By the end of the film, he is sorting out just the peels on a conveyor belt. You then begin A Ciambra with an image of a young Emiliano, Pio’s grandfather, when he was still a traveling Romani, slicing a lemon and drinking its juice, which then cuts to the present day, with Pio handling a lemon in his kitchen. Thematically this is one of our favorite elements of your first two features.

A: Carpignano: You know you two are killing me right now, because the scene that was the toughest for me to take out of the film is a scene after Pio’s brother comes back from serving time in jail, where he and Pio are sitting together the morning after their grandfather’s funeral in silence when Pio cuts a lemon and gives himself some citrus, and then he gives his brother a slice, and his brother eats it, and then the little boy comes in and grabs a piece of lemon and sits down in the chair.

Q: Generoso: Oh no, why did you cut this?! We so wondered why we didn’t see the citrus used as much in the film.

A: Carpignano: I am going to my editor’s wedding on Sunday, and I am going to make him pay (laughs).

Q: Lily: Also part of our sadness is that Generoso’s family is from Campania, and you know they have the prettiest citrus there, so we were a bit sad not to see it. (laughs)

A: Carpignano: Yes, it is the dominant agricultural element of that region. The plain is famous for the citrus industry. People say even further back that the ‘Ndràngheta started to form because of the bergamot, that bigger yellow lemony-looking citrus thing. The bergamot was one of the first things that they exported, and they cornered the market on that, and that was the beginning of their agricultural syndicates. So, citrus is a very prominent part of the plain, and that is where they got a lot of their commercial viability.

Q: Lily: Speaking of motifs, there is also a key visual motif of Emiliano and his horse that appears throughout the film. You begin A Ciambra with a scene showing Emiliano traveling with his caravan and his horse, and then, Pio sees his grandfather as a younger man with his horse as a recurring image/vision. Why does Pio see this? Is Pio one of the last of the members of the generation who is connected to the past of his grandfather, or is this past just romanticized because he has heard about it from his grandfather?

A: Carpignano: It is all of the above. This is very much Pio’s story, and I think that the film tries to, through being very specific through Pio’s experience, arrive to larger truths about the Romani community in general, and one of the most important things I think about that community is this solidarity that they feel that they have. History has a weight on all of us, and this sense of tradition is what makes Pio’s decision at the end the inevitable one. I think that the greatest limit and the greatest potential of this community is its solidarity, because, on one hand, they have created this really intense social network that has kept them alive for years. There, they always say, “No one here is going to die from hunger,” and that is is because they have each other’s backs. But in another way, Pio is unable to transcend the social architecture of that place because that tight knit community won’t let anyone else in or out, and I think that part of that is because they feel that they all come from the same tradition. They still refer to the others, mind you, they are as Italian as anybody, but they still refer to the others as “Italians” and themselves as “Gypsies.” And, why is that? It is because they believe that they have a past that is different from everyone else’s, and to me, that is what the horse represents. Pio needs to feel tied to the past in some way, shape, or form. He needs to feel as part of this tradition to justify, even to himself, betraying someone who might be even closer to him than his own brother. The sense of community, the identity politics that we all fall back on, is something that I think comes from this constructed identity that exists within many communities, and most specifically this one.

Q: Lily: Staying on Pio for a moment, another of his characteristics that we wondered about was his fear of closed spaces, specifically being enclosed in a space that is moving. What is the origin of that fear?

A: Carpignano: First of all, just speaking about the motifs, thank you for using the word “triptych” rather than “trilogy” before, because when you look at the great triptychs, they are really tied together through overlapping characters and motifs, even less than narrative logic, so to say. When you look at one of the great triptychs of all time, the Kieślowski Three Colors films, the things that tied those films together are not only the motifs and the use of color, but also the recurring actions. But speaking about Pio, specifically his claustrophobia, to me, that is less of a dramaturgical device as opposed to a psychological one—to come up with that and to put that in a film and find the right context for it, I had to get to know him better because that is something that actually happens to him. The elevator where Pio panics is my elevator, and that apartment is my apartment, and Pio has never gotten in the elevator to get to the apartment. Every single time, we had to go up and down the stairs to shoot that scene, and we had to rebuild the elevator, putting it on the terrace so that there is a removable wall for him. Pio is actually afraid of enclosed spaces, and he is actually afraid of things that go fast, and I find that to be incredibly fascinating because we are talking about people who historically were on the road in small spaces, in caravans, and in boxcars, moving together. Now that they have become sedentary, they almost have this aversion to these things. Moving too much, moving too fast, getting in an airplane, and getting in a train are things that he just would hate to do. And, that is why the train is there as a reminder in the background. There is the possibility of movement, of mobility, but now paradoxically, the gypsies feel more true to their tradition and their people and their identity by staying put. It is as if they have gotten this piece of land finally, and they are claiming it and saying that this is ours, and now that land is the source of their identity. So, that to me was something that was very important to put in the film, because in the end, when Pio is finally forced to move, he is enclosed in this tight space in this train, and he gets flashes of everything at this one point. He begins to freak out as he is put in the position to do something that he doesn’t want to do, and that connects him to his past, his present, and ultimately, that is where he gathers the courage to do what he needs to do. I felt that putting Pio in a position where he isn’t able to reflect on what he is doing, like when he is living through this phobia, this paranoia, brings out the raw emotions in him, and that is why I felt O.K. to open it up to that dream-like space again in that scene.

Thanks to Emily McDonald from Acme PR for her assistance with this interview. ◼

A Ciambra opens in theaters and on demand on January 26th.