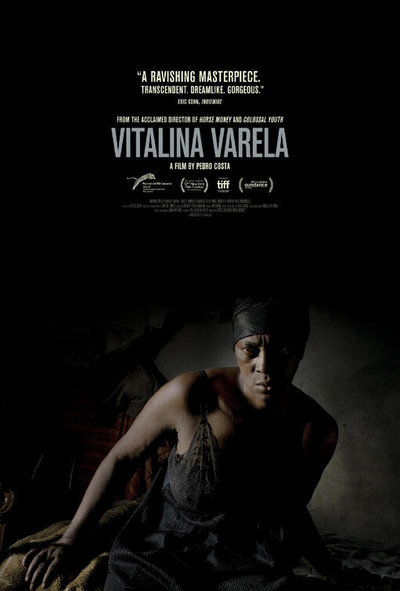

Vitalina Varela

directed by Pedro Costa

starring Vitalina Varela, Ventura

OPTEC

Emerging from a plane that has landed on a desolate airstrip in Lisbon is a singular faceless figure walking barefoot. The plane has traveled from Cape Verde to bring a woman to attend the funeral of her husband, Joaquim, who had left their homeland to work as a bricklayer decades earlier and who had promised, in vain, to purchase the woman a plane ticket so that one day they could be together. The woman walks from the airstrip, like a disembodied soul herself, through the darkened, maze-like streets and alleys of the impoverished Lisbon suburb of Cova da Moura to reach the hovel that was as much a false promise from her husband as it was a disappointing reality. The woman is the eponymous Vitalina Varela, and if this scenario sounds familiar, Vitalina once recounted these events in the early moments of Pedro Costa’s previous feature, Horse Money, and after six years, Costa, with Vitalina’s and the townspeople’s assistance, has reconstructed this heartbreaking moment from her life with a filmmaking process and visual style that has defined his particular approach to non-fiction storytelling.

The daylight, which is a rare sight in most of Costa’s work, is almost completely absent in Vitalina Varela, with only small strands of light filtering in through the fissures of doorways in Joaquim’s shack, which amplify the darkness and couple with the nearby faint sounds of people, radios, and cars to suggest to Vitalina that the home and surrounding neighborhood that belonged to Joaquim, now exclude her in his absence. Left alone with no one to comfort her, Vitalina rifles through the photographs of Joaquim, and she begins an investigation into her own past with him, wondering whether those days were truly ones with any hope for a positive future. Seeing the despair in the faces of Joachim’s colleagues and neighbors and the abandoned construction efforts in the house, Vitalina looks to the improvised memorial she has built for Joaquim in his living room and yells out to his spirit in search of any reason why he left her and Cape Verde behind to surrender to this desperate, crestfallen place.

As Vitalina is now forever tied to Pedro Costa’s work, so is, since his 2006 film, Colossal Youth, the presence of the actor Ventura, who in recent years has been in ailing health, and his physical deterioration is as much emotionally woven into the mesh of the painful narrative of the film as Vitalina’s recollection of her memories and mourning. Here, the frail Ventura portrays the local priest who offers services in his empty, decrepit church and who is one of the few to extend to Vitalina any semblance of real communication. Ventura becomes not only a connection to Christ and a sign that the townspeople have abandoned their faith during hardship, but also a metaphorical guide to Vitalina as he helps her understand how her husband had become intertwined into the history of exploitation of the people who traveled to this part of Lisbon aspiring for a better life. “Men were born out of the shadows,” explains Ventura, and as the film progresses and the reality of Joaquim’s dilemma grows more tangible to Vitalina, the endless darkness that has engulfed each frame throughout the film becomes not only emblematic of Vitalina’s sorrow, but also of Joaquim’s struggles and the pain and futility inside of all the residents of Cova da Moura.

Throughout Vitalina Varela, Costa continuously reinforces the brilliance of his established methodology: his distinctive audiovisual compositions exemplify and revitalize the longstanding tradition of portraiture. A good portrait artist captures the essence of reality, adds a layer of fiction/bias on it through perception/perspective and preserves the combination across time. As a result of his years of entrenchment in the physical edifices and lives of the people of Cova da Moura with his small crew, Costa is able to assemble an intimate, deeply layered portrait of Vitalina Varela from the living pictures captured by cinematographer Leonardo Simões’ masterful eye and the keen sound development by João Gazua and Hugo Leitão. And, due to Costa’s intuitive, time intensive construction of docufiction, we, the viewers, feel a heightened level of empathy for Vitalina that few filmed portraits have ever been able to accomplish for their protagonists.

In Vitalina Varela, Costa’s first film to feature a female lead since 2000’s Vanda’s Room, we witness the reconciliation of decades of sadness through Vitalina’s immersion into the oppressed community that once devoured her husband’s hope, and by this widow’s placement there as a body of maternal strength and survival to the men who suffered with him, Vitalina can ascend past her own sorrow by imbibing these men with the spirit of all of the women whom they also left behind.

◼

Vitalina Varela is available now through multiple local theaters’ virtual screening rooms, with half of the ticket proceedings going directly to the available theater of your choice.