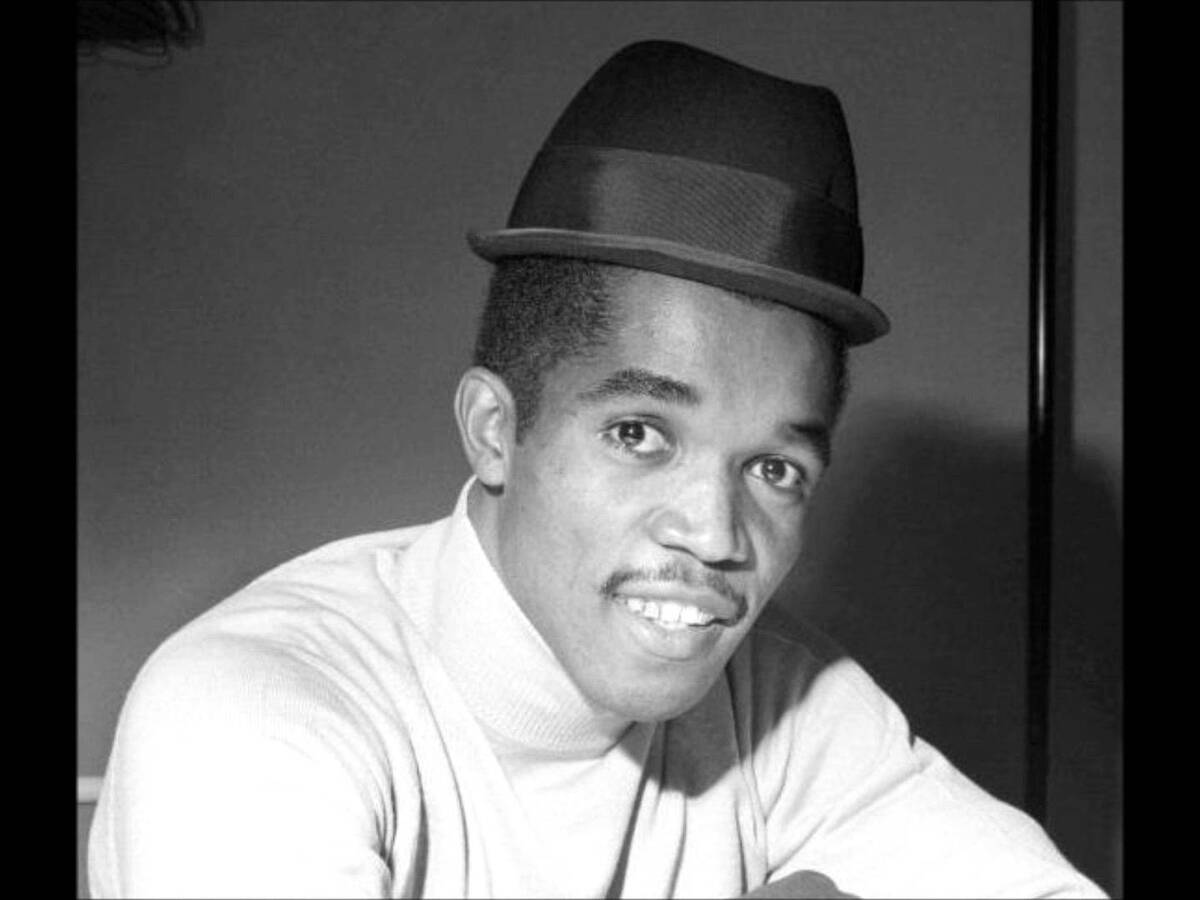

Prince Buster, RIP

1938-2016

by Generoso Fierro

There will never be another Prince Buster.

In a year that has seen some of the greatest talents in music pass away, I am sure that the same statement has also been made about David Bowie, Merle Haggard, and another extremely talented man with the moniker of Prince, but Prince Buster seemed to possess the best parts of the aforementioned musical idols who filled the latter half of the 20th century with their brilliance. The man born as Cecil Bustamente Campbell in Kingston, Jamaica in 1938 had the heartfelt soul of Prince Nelson, the hard life turned into song like Merle Haggard, and the inventiveness and audacity of David Bowie. Prince Buster didn’t have the greatest voice of his era of Jamaican vocalists, nor was he a virtuoso instrumentalist, and as a producer he could be a bit of a mess at times but make no mistake, The Prince would say, sing, and do anything to make his records sound more vital and unique than any of his contemporaries and that is why he inspired generations of musicians after him who decided to play the styles of music that he helped to make famous, and at times, infamous.

I worked with Prince Buster in 2002 when I helped produce a concert with him, Derrick Morgan, Patsy Todd, and Eric “Monty” Morris, all magnificent singers in their own right. It had been a dream of mine to see them all on a stage in Boston, a town where I lived for thirty years and did radio program, The Bovine Ska and Rocksteady, during the last twenty years before leaving for Los Angeles in 2015. The show took a lot out of us but in the end, in terms of music, it was one of the most satisfying experiences during my many years there. Buster headlined the show that evening and that decision was not just based on talent, it was simply because Buster’s reputation had preceded him and the people who heard about the show before it was officially advertised, usually reacted with amazement and with the question, “really?” I loved Buster’s music and his mystique, but I was impressed by the look of shock. Was it because almost every Two-Tone era ska group from Madness to Bad Manners to The Specials to The English Beat covered Buster songs, with Madness going as far as even naming their band after one of his hits? Or was it because Buster had popular songs back in the day like “Big Five” that were so filthy that the uncensored version would make Lil Wayne blush? I think that the answer begins in 1961, when Prince Buster, who had just begun a singing career, produced one of the most important records in Jamaican music history.

In the years prior to becoming a singer and producer, Prince Buster worked as a “bodyguard” and selector (deejay) for the very popular Downbeat Sound System run by Sir Coxsone Dodd of later Studio One fame, but Buster wanted to branch out on his own and after securing a loan from Tom Wong, better known to reggae aficionados as Tom The Great Sebastian, one of the earliest, if not the earliest sound system operators in Jamaica, Buster started his own sound system, “The Voice Of The People.” Like Coxsone and Duke Reid, Buster’s sound was doing well, but acquiring the precious new rhythm and blues records from the United States that were needed to stay competitive was becoming more and more difficult as trips to the States were getting harder to pull off, so Buster made another career move to become a producer and singer in the small, but rapidly growing Jamaican recording industry. For this new endeavor, Buster called on percussionist, Arkland “Drumbago” Parks, and guitarist, Jah Jerry, to help him assemble a group of instrumentalists for the recording studio which resulted in Buster’s first release as a producer and artist, a fairly forgettable Jamaican rhythm and blues track with sub-par vocals called “Little Honey.”

A few singles would follow to some success but Prince Buster needed a real hit for his young label to gain acceptance and being that he was not blessed with a show-stopping voice, Buster travelled to the Wareika Hills looking for a sound that would make his recordings distinct. On his return to Kingston, Buster brought Rastafarians, Count Ossie and his group of Niyabinghi drummers (then called Count Ossie’s Afro-Combo) back to the studio, where they played on “Oh Carolina,” a simple tune by the Folkes Brothers which The Prince made remarkable due to the inclusion of African-influenced Niyabinghi-style drumming and chanting, A few music historians have noted the precedent of “Oh Carolina” as being the first Jamaican recording to feature a Rastafarian performance, but to fully grasp the audacity of this collaboration you need a better cultural context.

By 2016, the western world has had over forty years of seeing iconic images of Bob Marley with his flowing dreadlocks and a joint in his hand and based on that, most non-Jamaicans normally make the assumption that Rastafarianism had always been an acceptable way of life in Jamaica, but let me assure you that when “Oh Carolina” was recorded in 1961 Jamaica, a country that was still under British rule, Rastafarians were viewed as a dangerous cult. Rastas were regularly harassed by police as the government saw them as a blight in a country headed for independence the following year with the hope of global acceptance. Despite the perception of Rastas by the people in power, “Oh Carolina” becoming a runaway hit helped solidify Prince Buster’s scofflaw reputation as the true “Voice Of The People,” a title that Buster would parlay into a folk hero persona that would become larger than life over his long career.

Throughout 1961 and the next year, Prince Buster would ride the success of “Oh Carolina” into a string of popular singles, some of which The Prince would sing himself, and other by a bevy of talented young singers including Frank Cosmo, Basil Gabbidon, Eric Monty Morris, and the man many describe as the first musical superstar in Jamaica, Derrick Morgan, who in one week had seven of the top ten songs on the Jamaican Hit Parade, a feat that has never been equaled. Derrick was indeed the crown jewel of Buster’s Wild Bells label, but Morgan’s sudden departure in 1962 from Wild Bells to work for the upstart Chinese-Jamaican ice-cream shop owner and record producer, Leslie Kong and his Beverley’s label would lead to a series of events that would further establish Buster as the undisputed “king of the rude boys.”

While at Beverleys, Derrick Morgan would continue as a hit machine and in 1962, he would score one of the biggest hits of his young career with the song, “Forward March,” a single that became the signature song for Jamaica’s Independence celebrations that year, but this continued success angered Morgan’s former producer, Prince Buster, a great deal leading a rather nasty exchange between the pair. Still upset over Morgan’s departure, Buster claimed that the solo that saxophonist Deadly Headley Bennett (late of this earth just a few weeks ago on August 21st, 2016) played on” Forward March” was stolen from one of Buster’s own hit songs, “They Got To Come”. As a form of retaliation, Prince Buster wrote and recorded the appallingly vicious track, “Black Head Chinaman”, which as you may have guessed portends that Derrick Morgan was not really black but Chinese. “You done stole my (Buster’s) belongings to give to your China Man”. Inflammatory lyrics that made the song a slam against Morgan and his producer, Leslie Kong. Derrick would respond to Buster with his own song, “Blazing Fire,” a composition that begins with Morgan reciting the following line in Chinese, “Shut up you idiot.” Things appeared pretty grim between the two former friends.

Subsequent offensive tracks were lobbed between the pair during the next year making this conflict the first record war in Jamaican music history. This battle would stir the interest of their individual fan bases, which at times even generated physical altercations between Morgan and Buster’s supporters with the real outcome being a huge boom in record sales and a furthering of Buster’s bad boy image. Surprisingly, when I interviewed both gentlemen in the early 2000s, they admitted to the entire affair was a fabrication created by Buster just to sell records. A pretty dangerous method to sell the public on some music, but Buster came out of the whole thing back in the day a bit richer and with his reputation as a man beyond reproach when it came to the music business.

After the “Blackhead China Man” stunt, the ska era would prove to be a great time for The Prince, but with the change of rhythm to rocksteady in 1966, Buster’s productions would take a backseat to rival producers, Coxsone Dodd, Duke Reid, and yes, even Leslie Kong, all of whom had the greater financial capital to lure the up and coming talent to their labels, most specifically the immensely popular vocal groups like The Heptones, The Paragons, and The Gaylads. Buster still had the talents of Roy Panton, Dawn Penn, and Larry Marshall for his new rocksteady imprints, Olive Blossom and Prince Buster (oh, yes he did), but the majority of his resources would be focused on his own singing career. There were some fantastic cuts by Buster during this era, including a mischievous sounding duet that The Prince would perform with a young Lee “Scratch” Perry entitled, “Johnny Cool,” but it was the series of “Judge Dread” records that Buster would talk his way through that would become of standouts of his rocksteady releases.

Though rocksteady saw a slowing down of the rhythm, it also saw an increase in crime in Kingston, as Jamaica was suffering from the post-colonial effects of independence from England. Foreign companies began rapidly destroying Jamaican agricultural land in their greedy attempts at removing tons of bauxite from the earth for aluminum production. Farmers who saw their livelihoods ruined flocked to Kingston in search of work, but with only a few jobs to be had in the city many of these displaced farmers turned to crime and thus, the “rude boy” was born. In response to this crisis, several musical artists began writing tunes about the rude boy’s exploits, some being sympathetic to their plight, while others, like Prince Buster, condemned their actions in song. To vilify the rude boy’s actions, Buster created the character of “Judge Dread” who would dispense wildly draconian sentences upon rude boys for committing crimes. These tracks, which had lyrics were never sung but spoken, were immediately copied by rival producers to limited popularity. To combat the mimicry, Buster would reprise Judge Dread in several subsequent songs including “The Appeal,” and “Barrister’s Pardon.” These releases proved so successful that years later, the English singer, Alexander Minto Hughes, would change his name to Judge Dread and like Buster, Judge Dread would assume a deviant persona that led to a two decade career which sold millions of the rudest records in UK history.

Once rocksteady had passed out of vogue and reggae had begun to pick up steam, so did the need to be more audacious on records. In 1968, Max Romeo, the lead singer of the rocksteady group, The Emotions, released one of the first runaway hits of the new reggae rhythm, “Wet Dream,” which is as filthy as it sounds. The race was now on to outperform the popularity of Romeo’s vulgar hit, and as he would not to be outdone in terms of scandalous material, Prince Buster would release the aforementioned, “Big Five,” a track eschews double entendre and so graphically describes the sex act that “censored” and “uncensored” versions needed to be released. Needless to write, “Big Five” was one of the biggest records of Prince Buster’s career, a record that was parodied by Judge Dread to equal fortune as “Big Six” “Big Seven” and yes, “Big Eight, Nine, and One too!” Years later when the whole Two Tone era took off, a blending of traditional ska and punk rock viscera, you can clearly see Buster’s influence. If bands like The Specials and Bad Manners weren’t covering Buster’s songs, they were embodying his attitude.

Throughout the remainder of his career, Prince Buster remained as bold and inventive as he needed be. In the short three days that I worked with Buster, I found him to be tough at times, joyous when the song worked, sweet at the end of the show, and pretty fucking exciting throughout. I threw that f-word in for you Buster, because I think you would’ve liked that. Rest in peace. ◼