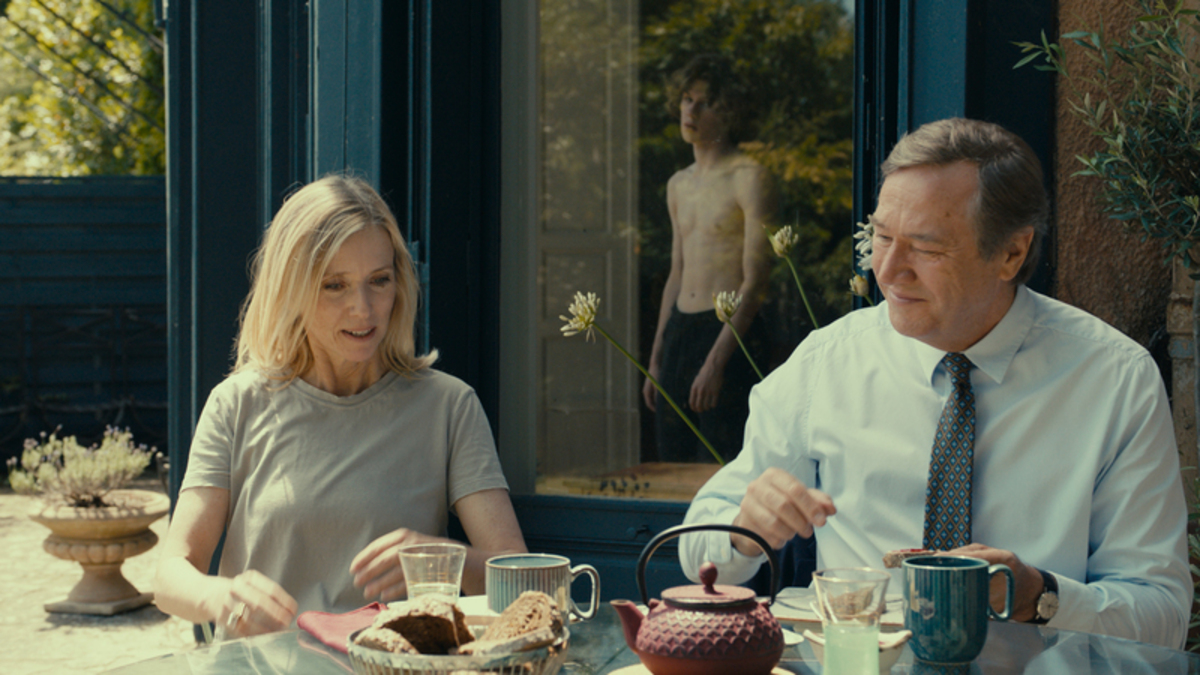

Last Summer

directed by Catherine Breillat

starring Léa Drucker, Samuel Kircher, Olivier Rabourdin

Janus Films and Sideshow

It has been a decade since novelist and auteur filmmaker Catherine Breillat presented her last feature, Abus de faiblesse (Abuse of Weakness), a harrowing, semi-autobiographical film based on her own 2009 book that delved into her real-life victimization by a notorious conman decades her junior. As had been the case for the predominance of Breillat’s oeuvre with works like 36 Fillette and Romance, Abuse of Weakness deftly and viscerally confronted our notions of intimacy and sexuality in a way that few filmmakers are able to achieve by forcing one into the uneasy skin of its protagonist.

Surprisingly, for her latest feature, L’été dernier (Last Summer), Breillat decided to reimagine the critically acclaimed 2019 film Dronningen (Queen of Hearts) by May el-Toukhy, in which a lawyer, who specializes in representing young women who have experienced sexual abuse, turns into the abuser of her own teenage stepson.

We’ve long admired Breillat’s distinct style as a filmmaker, often drawing from her own writings and novels, so learning ahead of the film’s release that she was trying to remake another feature — especially one this recent — was fascinating. Given the themes present in the predominance of her filmography and her recent experiences, it made sense why Breillat would be drawn to this particular story, but on description alone it was unclear how her idiosyncratic style would alter the narrative.

However, in the first minutes when we see the veteran actress Léa Drucker embodying the role of Anne in Breillat’s adaptation and hear the compact and effortlessly constructed and delivered dialog, Breillat’s signature approach firmly announces its arrival. In this initial scene, Anne is meticulously preparing a young female client for the virulent questioning from defense attorneys that will most likely occur during an upcoming trial. Anne is confident and raw in her approach, but we also see her as someone who possesses elements of tempered compassion: she’s severe because she wants her client to be prepared for the questions that will aim to discredit her testimony, but she also reassures her client that she believes in her. When the scene eventually shifts to Anne’s idyllic country home, we meet her husband, Pierre (Olivier Rabourdin), a beleaguered financier who tells Anne that Théo (Samuel Kircher), his teenage son from a previous marriage, has gotten into trouble that is beyond his mother’s capabilities to handle and must move in with them for an undetermined amount of time. This potentially upsetting addition to their blissful family dynamic, which already includes two adolescent adopted Asian daughters, is agreed upon with no argument from the loving couple.

Once Théo arrives at Anne and Pierre’s home, he gives off the classic appearance of a rebellious and mildly cosmopolitan teen who has been exiled to the sticks as a form of punishment, but as he settles in, his behavior vacillates between bratty (almost on the verge of malevolent) and gleeful. He throws verbal barbs at his father that most of us would shudder to think of, and yet he readily accepts the role of a doting older brother to his stepsisters, whom he adores almost instantaneously. Anne’s first reaction to Théo’s jibes thrusts her into an authoritarian figure, but after Anne agrees to never speak of an aggravated transgression from Théo and brokers a deal with him to protect the stability and cohesiveness of the family, the separation between the stepmother and stepson dissipates into an unspoken connection. And, the once stern talks give way into cigarette sharing hangs behind the house and Anne riding pillion on Théo’s scooter though the countryside to a local bar, where the two speak openly with a camaraderie likened to that of close friends.

Inevitably, when the ever-growing sexual tension between the two materializes into a physical act, Breillat tightens her focus on the level of warmth, comfort, and intimacy between them, suggesting that their bond comes from more of an empathetic place than simply a carnal one, which is a key point of departure for Breillat’s rendering from the original Queen of Hearts, where Anne’s attraction to her stepson stems from a simplistic need to feel younger. Initially, Breillat lets the carefree moments between Anne and Théo happen from a safe distance that never feels contrived, and although it’s unsettling to watch, every second between the pair says volumes about Anne’s current mental state while naturally alluding to the very personal reasons why she decided to become a lawyer for abuse victims. Astonishingly, through the careful execution of the verbal and physical interactions between Anne and Théo, we even come to see Anne as a victim herself, but when the potential exposure of their illegal tryst becomes eminent and Anne breaks off her relationship with Théo much to his discontent, we see Anne radically shift from victim back into an attorney who knows the language of abuse and can use it to her advantage in silencing her stepson’s allegations.

Besides the drastic change in outcomes between the two films, a difference which may heavily suggest why Breillat chose to make this adaptation, the key to Breillat’s affecting interpretation of Queen of Hearts is the director’s decision to remove all elements of melodrama that were hard-wired into May el-Toukhy’s film. Breillat’s choice softens the obvious points of contention in the film related to the morality of Anne’s actions, which orients Last Summer far away from a sensationalistic, manufactured drama and towards its in-depth and compelling analysis of Anne as a mother, wife, woman, and foibled human. We (and Anne herself) absolutely know that she should not have a romantic relationship with Théo, but Breillat doesn’t expend energy on trying to rile up judgment from the audience towards Anne to encourage an air of superiority. Instead, the director guides us through Anne’s actions, motivations, and responses, all of which become understandable, albeit uncomfortably so.

Ultimately, Last Summer sets itself apart from Queen of Hearts with a tone more akin to Agnès Varda’s 1988 film Kung-Fu Master!, another subdued and nuanced film about the illicit relationship between an older woman and an underaged boy. Breillat artfully infuses her long-cultivated sensibilities into every aspect of Last Summer in a knowing way that tempers the overtly audacious delivery that was more present in her earlier films while still continuing to question and challenge our assumptions about how factors such as class, power, attractiveness, and trauma can control and distort women’s desires as well as the subjects of their desire. Both Varda’s and Breillat’s pieces benefited from the skillful artistic vision of seasoned filmmakers who fearlessly examined the complexity of flawed women who, despite their outward appearances of stability, have psyches and pasts that betray their best intentions.

Last Summer is currently screening in theaters across the United States. It opens in Chicago and Cambridge on Friday, August 16, 2024.

Featured photo courtesy of Janus Films and Sideshow.