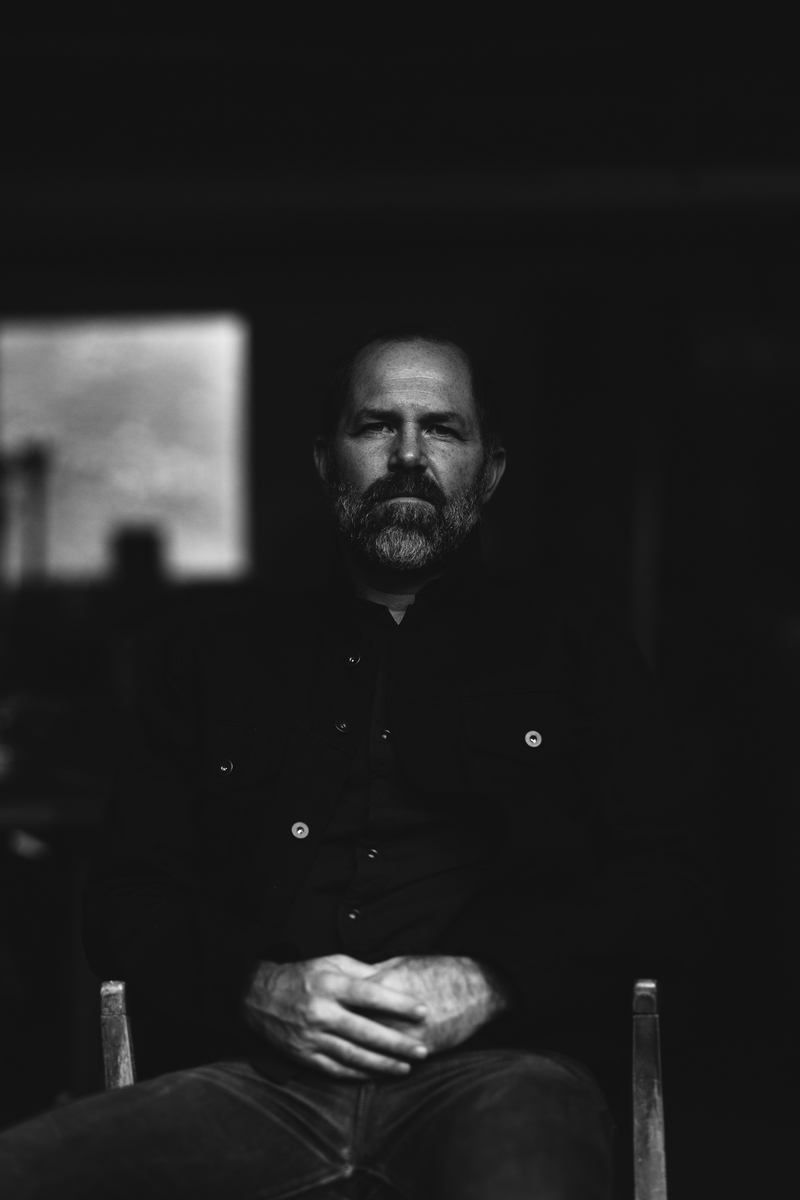

Jeffrey Foucault

Questions, connections, and satisfaction in the absence of answers.

Where Jeffrey Foucault lives, there are no stop lights and no fast food. “I love it,” he says.

We had a chat in August, a month before the release of The Universal Fire, Jeff’s first album in six years as well as his first on Portland-based Fluff and Gravy.

This “no fast food or stop lights” living in rural Massachusetts comes through in his relaxed tone and carryover Midwestern down-to-earth vibe. I can hear birds in the background as we talk on the phone. He’s happy where he is, but is still very rooted in his native Wisconsin. Go Packers!

His dad grew up in Milwaukee, and his grandfather, a city worker, eventually became “the guy that was in charge of all the lights in the city.” The irony hits me after we speak. From a grandfather who was in charge of traffic lights, to living in a town with none. Jeffrey is a natural at connecting the dots. Timing is important, from traffic lights to songwriting.

• •

I asked Jeffrey Foucault about the process of putting The Universal Fire together. Was it intentional to go so long between albums?

“In that period I probably wrote 50 songs and I could have made any number of different records, but two things happened: Billy Conway got sick, so he wasn’t able to go into the studio (I wasn’t going to make anything without him), then COVID happened. Because he was immune compromised, I could visit him one-on-one if I was careful, but we couldn’t tour together.”

Billy didn’t want to make a record if they couldn’t tour together. It was part of their bond. When they began traveling together, Foucault tells me they did over one hundred nights a year in the course of a decade.

“Being on the road,” says Foucault, “actually playing shows, was so important to Billy and how he wanted to create music. It’s like you’ve never been anywhere else. You get on the road and can’t remember ever having been home. And when you’re home, you can’t really remember having been on the road. It’s an oversimplification, but it indicates something that I think is largely true. He liked to be all the way in. I think he just wasn’t willing, given his condition.”

From what he had written, Foucault culled about twenty-five songs that might work. Part of that process was convening a band and seeing what everyone gravitated toward. The band cut all the songs, and eventually narrowed down to the ten that appear on the record.

When asked about having John Convertino on the record as well as some tour dates, Jeffrey was clearly honored as a long-time fan.

“I had wanted to work at Wave Lab since I heard Richard Buckner’s record, Devotion and Doubt back in the ’90s, which John and Joey from Calexico played on. I’d thought about making Blood Brothers at Wave Lab. Anyway, It just happened. I knew John, going back to when I was opening for Tiff Merritt, and he was in the band. I’ve had a chance to say how much I love his playing, not only on that record.”

The Tucson connection is a deep well. Foucault connects the dots seamlessly.

“There was a slide guitar player named Rainer Ptacek. It’s a strange East German name for a guy that played American slide guitar blues. Rainer was the guy, like the daddy of the Tucson desert rock scene. He had a band called Giant Sandworms that became Giant Sand with Howe Gelb. John Convertino was the drummer in that band, and Joey Convertino was the bass player. When they split up, Joey and John made Calexico. Howe went off and did his own thing and kept Giant Sand going in different forms over the years.”

“When I realized that John had not only played with these other people that I really love, like Buckner, but had also played with Rainer, who was one of my songwriting, guitar, musician heroes, I just felt like Tucson was the place to go. John actually lives in El Paso now but he was in Tucson for twenty-odd years. I went to him and I said, what do you think about this?”

And what did Convertino think about it?

“He was down with going back to Wave Lab and being in Tucson. We had a really magic session. It was just a delight; a beautiful band. Heywood and I knew John. John didn’t know anybody else in the band. Then there is Mike Lewis (Bon Iver), who produced the records and plays horn on “Monterey Rain.” Lewis had done some arranging for me on a thing that I made during the pandemic that I haven’t put out yet. He had these really great, very sideways, basically sophisticated string lines that he’d written. He doesn’t try to make anything that sounds like Americana”

Reflecting on Billy Conway and how his passing affected the choices for this record, I asked Foucault about Convertino’s minimalist style and how it is close, but also in contrast to how Billy played.

“One thing I’ll say about John and Billy, they have their differences stylistically. John can play with real force and power, but he never plays like a caveman. With Bill, if I told him to play like a caveman, he could. He’s just gonna bang on some shit and it’s gonna be completely raw. John always has a sort of elegance, a refinement and delicacy to his playing, which Billy was capable of, but didn’t always choose to do. They hear the beat in the same place and they play very similarly to a point.”

“I was writing these tunes and I knew that John was coming to the session. I sent demos to everybody, and he showed up and played exactly what Bill would have played. We go out on the road and he’ll play a song he’s never heard before, and he plays it, uncannily like Bill would. That was really special to me. He’s just a very magical musician and human being; a great human being.”

Foucault elaborates on the often overlooked connection between great musicians and great character.

“If [musicians] were better human beings, they would be better musicians. Isn’t that something that Coltrane said about trying to be a better human being in order to be a better musician? I think it’s a deep thing. It eventually melds together.”

I want to know more about how the making of this album contributed to his healing process after Conway died. It feels cliché to ask, as I hear so much about art and music being therapeutic during grief. Foucault assures me with his answer.

“Clichés are clichés because they’re often true enough that they attach that kind of information, but it was certainly part of the process. A big part of the process is to just pay attention. If you hide, you’re gonna deal with it anyway, so it’s best to just try to get squared up on it, and feel how you feel in the moment.”

I feel better about asking now. He continues.

“I went away for about a week the next month after Bill died, right before the holidays. We got through the holidays and then that month. I said, all right, I better go somewhere and just pay attention for a week, so I don’t do what I think it’s tempting to do, which is to look away from it, or get busy doing something else.”

Foucault did just that. He finished some of the songs and worked on others. He found a cabin to rent in January about thirty miles from home and holed up with a wood stove and a bare minimum of comforts. He brought his snowshoes. The solitude clearly helped bring out songs, not as a preconceived “statement.”

“Often enough, a song is like a speech. You begin with the idea. In our corner of the music business you sometimes or frequently begin with the idea that you have something that you’re going to tell people. And then, it’s like a box that you just fill with related details. I find that, generally speaking, pretty boring.”

I ask him to expand on this concept as it relates to the title track, “Universal Fire.”

“What I wanted for that song was that it didn’t present any particular conclusion. It’s a question, right? The question of that song, and to some extent, of the record, is what does it mean to lose things? Okay, so you burn up the masters of Billie Holiday, right? You can’t get back to those original masters and manipulate them or exploit them anymore for new information with new technology or get closer to the source itself. And so the third verse, ‘gravity pushes down the stylus and God disappears into the sky’ that’s about the physical process of plating a master recording.”

Then as you go along, everything you made, everything any of us has made, will disappear. If you’re looking long-term, there won’t even be, like, plastic in the fossil record. Eventually, there will be absolutely zero trace that any of us ever existed, which is comforting to me on a given level. If you can lose it, did you have it to begin with? That’s one thing. Then what does it mean to have things? What does it mean to lose them? Those are questions that move around. I don’t think the answers really stay put, either. So I try to keep the stance of the record, open and questioning as opposed to giving people a pat statement about what it means for this thing to happen. Now I need to just sit down and think about this. That ability to have a song be a question instead of tying it up in a nice neat bow at the end, and here’s the deal and Hollywood ending.”

I ask Foucault if his obvious affinity for literature of any type influences how he sees the song as more of a question.

“I think those things are all totally connected, and at this point I probably write poetry as often as I write music. I don’t publish it, but as an exercise, I write it. It has completely different imperatives than lyric writing does. With lyric writing, you’re consistently shackled to some extent, like pleasant sounds that tend to end, that tend to end in rhyme, which is annoying and boring. With poetry, you can’t fall back on the melodic information that we respond to, and you can’t rely on what I would describe as the spiritual charisma of the singer, which can be very compelling and can make bad material totally beautiful, right?”

Foucault has also been painting, which ties in nicely.

“When you’re talking about asking a question… what’s interesting to me is the subject that generates the impulse to write. So you see a thing, you think of a thing, you feel a thing, and you say, I’m gonna write a song, but the mistake, I think, that gets made, especially when people are starting out, is they think the song, or the poem, or the painting is going to be about the subject that generated the impulse.”

“And the subject, the real subject, is the one that you discover in the process of making the thing. A good poem, for my money, makes a turn somewhere in the course of the poem, and that turn is where it stops being about what you were thinking of when you began to write it, and it begins to be about itself, which is this process of discovery that has more to do with your unconscious mind, probably, and your obsessions and the particular sounds that you are obsessed with for whatever reason. Those things show up with painting, because painting is essentially additive or creative, however you want to put it. You make a mark on the paper and each mark after that you are responding to what’s already there. I’ve carried those lessons about process into my work.”

Foucault reveals his distaste for political songs.

“I don’t like songwriting that says ‘here’s the thing and I’m going to tell you about it.’ That doesn’t mean I don’t enjoy literal songwriting. I don’t think Ted Hawkins or Otis Redding ever wrote a metaphor in their lives, right?”

Foucault gives me so much to think about, as well as new Otis Redding earworms. He’s right about the lack of metaphor in some of the most revered classics.

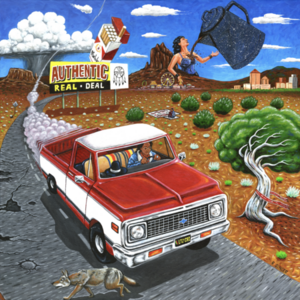

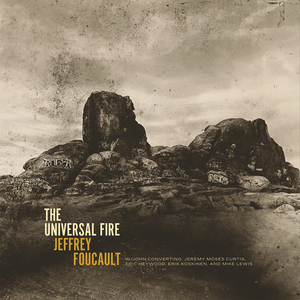

I turn the discussion to the cover art, which is stunning and also not “literal.”

He gives kudos to Brandise Danesewich, who is under the moniker @antimodel on Instagram. He approached her, assuming she was “too good” to have any interest, and of course she nailed the mood of the record. He knew he wanted landscape as the cover art, and Brandise ran with it after hearing the songs.

As I listened to each track of The Universal Fire, I became curious which of the songs might be Foucault’s favorite, which I find, for other artists, usually isn’t the song that goes to radio first as a single.

He points to “Moving Through.”

“What I love about that track is that I finished it on my knee in the car on the way to the studio that morning. The band hadn’t heard it. I was just noodling around trying to get my hands to work in the morning. Mike and I were having coffee. We all stayed together in a little rented house in Tucson that I found. So we’d all go back and we’d do our daily playback. Have a drink, make some food, etc. I like having everybody in the same place for that reason. Then, we went in the morning, so I was playing this tune, and he was like, what is that?

“I said it’s one of the tunes, but it’s not really done. And he was like could it be done? I was like, yeah, probably. I can just finish it.”

“I maybe cut one verse away and added one verse or changed it. We recorded, and I just kept playing the riff while everybody was setting up, right? I like that the track starts with me saying, ‘are we rolling’? Nobody knew anything about the song. They didn’t understand that there was a form. And we invented the song and the form as we recorded it. So what you hear is the one take of the song, and everybody learned it in real time.”

“It’s like the eye of the hurricane, right? Like the record moves around this one track, and the track is a more general wide-lens look. It’s like looking at the world, which is strange and terrifying and doesn’t make any sense, but it’s yours and you just keep moving, right?”

“The whole point is this: I just keep moving through this thing, whatever it is. Sometimes it’s beautiful and sometimes it’s not. But, this is what we have and you have to just keep moving. To me that’s the… well it’s not an answer, but it is one answer to all the questions that are posed on the record.”

Foucault gives credit to his band, who can roll with whatever is thrown at them.

“Yeah, they’re such an outrageous band. I like the idea that we get to go out this fall and really drop into gear.”

I ask him about the discipline of touring together compared to recording.

“You start out and you’re remembering how to do something that you’ve already done. And then when you really get into it, the more discipline there is. This is something I really learned from Billy, right? There was about a year where he made me play the same set every night. I’ve always been too ADD to pull that off. I’d get bored and I’d get antsy and I’d start changing shit. But I trusted him and I respected him enough that I stuck with that. And what he taught me was discipline.bias.freedom. You can’t have freedom first.”

Foucault remembers a pivotal road experience with John Convertino.

“John and I did a duo tour where all I brought was an electric guitar. We were down in Texas in January and he brought his kit. I picked him up in El Paso and it was just drums and guitars, which I hadn’t done since Billy and I were out. We did the first show in Austin and we were loading into the car and John said “Billy was helping me out tonight.” John’s just that kind of guy. He’s very in touch, right? Very open. It was the most beautiful thing. And I was like, I totally believe it.”

After speaking with Foucault, what stays with me is his humility, a keen ability to see connections in forces that might not be so obvious, and his awareness of the big questions. He’s been presented with some tough ones in the last decade. He’s happy to ask those questions as he creates. He might drop the listener one small answer in the process, but there are no Hollywood endings. We ultimately have the freedom, if we listen closely, to connect the dots as we see fit.

I am certain Billy Conway would approve. ◼