Michael Welch is a Hero: He Saved His Dad’s Life

by Mike Welch

In the tradition of other great columns, such as the ones that supported the buildings of Rome: my column for Ink19 will be straight and strong and dependable. You, readers, will enjoy my column, consistently. I promise you that, with complete confidence.

But, though I have confidence in my ability to please you, I am currently mired in self-doubt in regards to a concept for my column.

My original column concept, I realized, was alarmingly contrived: I planned to go out on the streets of Tampa and, once a week, attempt a one-night-stand for the purposes of recording the event and sharing it with you. But I abandoned that idea when my first attempt ended with my lying sexless and alone in a half-empty, freezing-cold bathtub in some strange woman’s apartment.

The hot water ran out several inches below my bent hips, so I turned off the faucet and sat in vain in the half empty tub, waiting for her to join me, my member perpendicular and only half-submerged, like a ship in a marina.

The water quickly grew icy and I was forced out of the tub. But even before I walked naked down the hall to her bedroom, wrapped in gooseflesh, only to find her in her bed, asleep and uninterested; I had known I would need to think of a better concept for my column.

I dressed and let myself out of her apartment, humiliated, pondering other options.

Other bad ideas included: trying a different illegal drug each week and reviewing it, making someone cry once a week and documenting the process, or getting in a physical altercation once a week (a bar-fight or something) and writing about that. All for you.

But I’m not a tough guy and I couldn’t put myself through those kinds of things without ending up in a lonely place; incapacitated with STDs and crying my two black eyes out.

Really; I want to be loved, not rotten with disease and sorrow.

Even one of my favorite writers, who I correspond with via email, concurred that the first draft of my Ink19 column was shit. She told me I should charm, rather than put off, my audience. She encouraged me to seduce you, dear reader, romance you. Oh, she made it sound so nice. Because I do love seduction, I love romance, yes.

I took her good advice as Hemingway from Gertrude Stein, and will attempt to court you with the following charming moment from my life, in hopes that you will care about and appreciate what I write in the coming months. Because I really want this to work out: you and I. Here you are, love…

I AM A HERO:

When I was a child, my father owned a used car lot in my hometown of Gary, Indiana. Gary is the birthplace of all the Jacksons. I’ve been to their house.

But aside from the city’s Jackson legacy, Gary is bleak. People there are very poor, tense and angry.

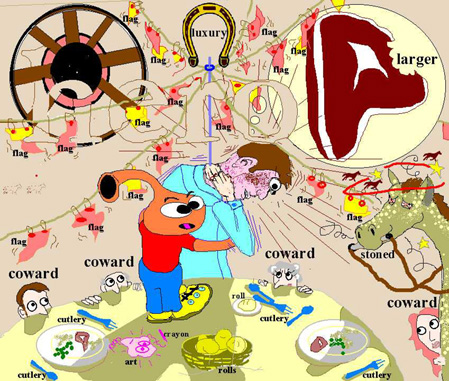

I don’t remember much about my dad’s car lot: I remember streams and streams of multi-colored plastic flags suspended high above my head in circus tent fashion, loudly whipped by the wind. I remember a bright red sign announcing, WELCH AUTO SALES. I also remember being woken up and dragged to WELCH AUTO SALES at 3 a.m., several times a month, whenever the police called my parents down to the lot to fill out reports on their stolen cars.

I also remember my father once winning a free weekend at The Wagon Wheel Resort in Michigan from General Motors, for our entire family, in honor of him selling an extraordinary number of Chevys.

The Wagon Wheel Resort sported an Old West motif: hardly a ‘resort’ aesthetic to most people’s sense of the word. It was more like a Ponderosa Restaurant. But it had a swimming pool.

An outdoor swimming pool in Gary is worthless 85% of the year, so the Wagon Wheel’s pool was one of those funny-smelling indoor chemical baths. Regardless, if it had been a pool of pure urine, my sister and I would still have played Marco Polo in it; in Indiana, any pool was the definition of luxury.

I had never been to a resort before: the word “resort” seemed to promise luxury. Though my concept of luxury at ten-years-old was questionable.

Any time my sister or I refused a meal at home, my mother would sardonically say: “Oh, maybe we should go eat at Red Lobster. Maybe you’d rather have Red Lobster every night.”

But our family never ate at Red Lobster, ever. So my mother’s fetishizing and mystification of the restaurant mislead me into thinking that only rich people ate at Red Lobster, that it was the pinnacle of luxury.

The first time I ever ate there was when I naively booked Red Lobster reservations for my date and myself on prom night, under the assumption that it was the swankest joint in town. I was excited to finally taste the untouchable good-life for myself.

I noticed the underwhelmed look on my date’s face as we rolled into the Red Lobster parking lot. But it wasn’t until I stepped in the door with my date’s soft, corsaged hand in mine, that I questioned to what extent I should ever again trust my mother. I also re-evaluated my idea of luxury. Again.

My first re-evaluation took place at The Wagon Wheel Resort while riding the sedated horses around in lazy circles inside the giant tin gymnasium that served as Wagon Wheel’s personal ‘stable’. The poor horse’s back sagged under me and its eyes sagged under the weight of the drugs it had been fed so it could tolerate little kids bouncing on it while The Wagon Wheel staff dragged it around by the bit in its mouth.

After a full day of riding drugged out, 1 1/2-mph horses we assembled in the luxurious Wagon Wheel dining room for dinner.

At dinner on the last of our three luxuriously free nights at The Wagon Wheel, my father ordered a steak. The initial steak brought to him by the wait staff of The Wagon Wheel was as brown and inviting as the Mid-Western wood paneling prevalent throughout the resort. But the steak was also kind of dinky. And since no guest of The Wagon Wheel Resort in Michigan should ever concede to anything but the best, my father guiltlessly sent the inadequate steak back for a bigger one. And he ate it with total disregard for all spectators.

My father grew up on a farm alongside seven siblings (7 boys, 1 girl – guess which religion these people practice). He eats his food as if participating in an eternal race for seconds; a resonating habit from his childhood, competing around the dinner table. His mouthfuls are big and he swallows them quickly, with his past and his future in mind.

But the luxurious, gristle-saturated, Wagon Wheel steak didn’t agree with my dad’s farm-boy, hyper-mastication and, on its way down his throat, the steak refused to go any further until chewed properly; leaving my father in an awful, bile-producing bind.

His choking began as an unusual, muffled coughing. I’m sure that, having eaten in fast motion like a starving cow all of his life, he had to have choked before. Which might explain how he did such a wonderful, expert job of covering up his dire situation. He nonchalantly choked for almost a minute before changing colors. Which, at 10-years-old, I found very funny.

The Wagon Wheel had luxuriously equipped our table with crayons and so I began drawing a picture of my father’s colorful, air-deprived visage on the paper tablecloth. I dropped my purple crayon when he stood up, scratching at his throat.

His muffled cough was now a loud, ripping choke causing the other 100 or so people in the dining room (who had all paid for their fancy weekends at The Wagon Wheel) to look up from their luxurious meals in mild panic. But no one got up; they just murmured loudly. I remember thinking, at ten-years-old, that the staff and guests at Red Lobster would have far too much class to ever let my dad stagger and suffer.

The Wagon Wheel’s lazy, indoor-pool swimming, resort-softies didn’t budge, so somehow, I channeled the spirit of Heimlich, walked in back of my choking dad, wrapped my short, ten-year-old arms around his sternum and squeezed abruptly.

<a href=http://www.screwmusicforever.com/commonplace/entries/chokepic.html>See this image in glorious full-size!</a>

When an adult finally did get up, it was to pull me off of my father. I suppose he assumed I was attempting to give my dad one last frantic goodbye hug before he died his inevitable gristle-induced asphyxiation death on the thinly carpeted floor of The Wagon Wheel dining room: surrounded by rusty relics of America’s cowboy days.

The adult’s big hands wrapped around my arms more adequately than my arms wrapped around my father’s convulsing chest. The adult whispered in my ear; “It’s O.K., there’s nothing you can do.,” and tried to pull me off my father. But not before I got in one last hard Heimlich. My dad’s choking stopped.

At first the silence denoted to me that he had died. But eventually, somewhere in that frozen moment, he turned around to see who had saved his life. While the adults had been trying to figure out how to get the loud choking man out of the dining room so they could get on with their meal, his ten-year-old son had saved his life. I had taken care of the whole situation before my baby sister even had a chance to cry.

As we exited the restaurant, I actually, swear to god on my life, heard someone say, “I was just about to do that.”

My father, who is a kind, loving, almost selfless man, has never been outwardly appreciative of my saving his life. He thanked me and that evening, took me to the resort’s luxurious indoor bowling lanes where I scored 133: my high score up till then (I was on that night) but he never made a very big deal out of it beyond that. I always assumed he was embarrassed in some capacity.

When the reporters interviewed me the next day for the Gary, Indiana local paper, asking me where I’d learned the Heimlich Maneuver (there isn’t a whole lot going on in Gary), I said, “From watching The Snorks.” This was a total lie, I have no idea where I learned it: but The Snorks were my favorite cartoon and The Smurfs were really whooping their asses in the ratings. The Snorks soon vanished from the airwaves, but I tried to do my part for them.

But my instantaneous, innate channeling of the Heimlich Maneuver leads me to believe that somewhere, down deep, I am a good person. Definitely not the kind of person who could write a weekly column about manipulating women, just for laughs.

In fact, the Gary, Indiana newspaper’s front-page headline the next day read:

Michael Welch is a Hero: He Saved His Dad’s Life.

The article left out my big-up to the Snorks and instead quoted me as saying, “I learned it from cartoons.” This would not be the last time I would feel very betrayed by the press.

But I will never betray you, dear reader. I will never misrepresent you. A hero wouldn’t do that.