Recently on Ink 19...

A.J. Croce: Live in Davenport, Iowa

FeaturesA.J. Croce celebrates the 50th anniversary of his father, Jim Croce’s, three ground breaking albums, with a nationwide tour of Croce Plays Croce.

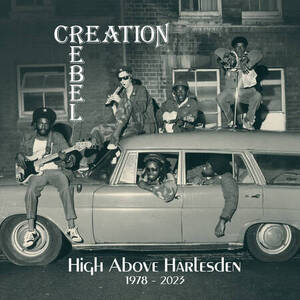

Creation Rebel

FeaturesHigh Above Harlesden 1978 - 2023 from On-U Sound collects 60 dub and reggae tracks from Creation Rebel, an astounding set of musicians.

Mushroom Daydream Coloring Book

Print ReviewsGerta O. Egy’s beautifully drawn fungi almost eclipse their fairyland habitats in her Mushroom Daydream Coloring Book.

The Valiant Ones

Screen ReviewsOne of the last of the classic wuxia swordplay films stands as a fitting coda to the grand period of the genre. Phil Bailey reviews a new Blu-ray release of the 1975 film The Valiant Ones.

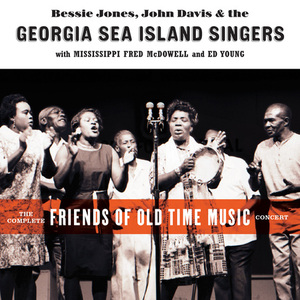

Bessie Jones, John Davis, and The Georgia Sea Island Singers with Mississippi Fred McDowell and Ed Young

Music ReviewsThe Complete Friends of Old-Time Music Concert (Smithsonian Folkways Records). Review by Bob Pomeroy.

Smash Mouth featuring Barry Williams, “Sunshine Day”

Music NewsSmash Mouth takes us back to The Brady Bunch circa 1973, with “Sunshine Day,” featuring Barry Williams, the original Greg Brady.

Best of Five

Screen ReviewsNot everyone can be excited by blocks spinning on a screen, but if you are, Ian Koss recommends you pay attention to Best of Five.

The Inspector Wears Skirts, 3 and 4

Screen ReviewsThe final two films in the bonkers Hong Kong action comedy series The Inspector Wears Skirts hit Blu-ray from 88 Films.

In the Line of Duty: Royal Warriors and Yes, Madam!

Screen ReviewsA pair of early “girls with guns” action films from superstars Michelle Yeoh and Cynthia Rothrock have arrived from 88 Films.