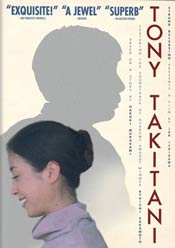

Tony Takitani

directed by Jun Ichikawa

starring Issey Ogata, Rie Miyazawa

Wilco Co. Ltd.

No one quite captures the ubiquitous sense of modern alienation like Haruki Murakami. That his uniquely Japanese sensibility has such a universal resonance that its quirkiness transcends translation difficulties is something of a marvel. While his work has been shown to easily triumph the language barrier, it has, up to this point, yet to be updated in a different medium. Jun Ichikawa’s attempt at Murakami’s short story “Tony Takitani” should serve as an example for what will likely be a slew of successors. The film relies on the concept of less is more, coming in at less than 75 minutes, Ichikawa’s version is remarkably honest to its source material,

Tony Takitani’s titular character stands at the nexus of three independent relationships that define his life: his father, his wife and his wife’s successor. All four characters seem to exist in their own private bubble, living oblivious to the expectations of the world around them. The film’s first narrative chunk deals with Tony’s father, Shozaburo, and his eternally adolescent lifestyle, his escaping Japan to China during World War II to play in a jazz band, his subsequent internment and threat of execution at the hands of the Red Army and his eventual return to his homeland. He marries only to have his wife die mysteriously two days after giving birth to their son. Completely divorced from the emotions he’s “supposed” to be experiencing, Shozaburo retreats into music, alcohol and the company of the American military still occupying Japan. At one of these men’s suggestion, Shozaburo names his son Tony, not recognizing the scorn an American name will inspire in the native Japanese population. Ichikawa handles this material through omniscient narration and a documentarian’s eye, cycling through old photographs and articles from the past.

Due in large part to his foreign name and his traveling father, Tony grows up in solitude, adapting quickly to an isolated lifestyle and learning to extricate himself from true emotional connections, just like his father. He excels at drawing, specifically machines and objects of minute detail; he immediately becomes a sought-after artist. Inexplicably, one day he falls deliriously in love with a young female client named Eiko. He tells her “I’ve never met anyone who inhabits her clothes with such obvious relish as you.” Her response is that her clothes fill up what’s lacking inside. Tony’s love and understanding only for the superficial and Eiko’s devotion to maintaining a flawless appearance soon blossoms into a co-dependent love affair and subsequent marriage. Through this, Eiko’s insatiable appetite for sartorial consumption escalates, as does Tony’s burgeoning fear that, after having finally made an emotional connection, he will not be able to function as a solitary person again. As Eiko’s buying habits spiral out of control – the couple eventually has to convert an entire room of their home into a walk-in closet – Tony tries to gently stem the tide of her unnecessary spending. Despite the good intentions, Eiko meets her fevered end just as suddenly as Tony’s mother, leaving Tony with the ghostly reminder of his wife in the form of racks of expensive clothes. The final act of the film features the most Murakami moments of surrealism and heartbreak.

“Lyrical” is a word too-often bandied about in film criticism, but for Tony Takitani it rings true. Ichikawa keeps his scenes short and to the point, encapsulating as much information and character development in a gentle pan of the camera as from unnecessary dialogue or montage. The film is also imbued with Murakami’s sly wit as each character steals the closing statements of their respective exposition from the narrator. It’s as if the characters all draw from a collective unconscious that binds them together in melancholy yet keeps them psychologically stranded. Likewise, the minimalist settings used throughout the film act to reinforce the spartan loneliness inherent in these characters. The few grasps at beauty –like the slow movement over the clothes hanging on the racks of Eiko’s closet– are tainted by muted colors and the blurred edges of a lack of focus.

Ichikawa ends the film in a different key than Murakami, but hits the same note. Tony is allowed to make one final attempt at a human connection, despite the oddity of its circumstances and fails. His story ends with him more detached but all the more knowledgeable about his isolation than he’d been at the most solitary times of his early adulthood. The audience is left to ponder the cause and effect that has brought Tony to this point and the delicate balance necessary to navigate to fully appreciate the opposing ends on the spectrum of the human condition.

Tony Takitani: http://www.tonytakitani.com/e/