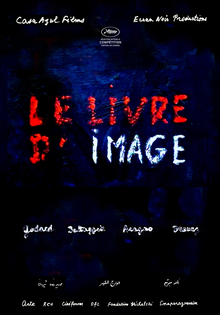

The Image Book

directed by Jean-Luc Godard

Casa Azul Films and Ecran Noir Productions

The 88 year old voice of Jean-Luc Godard is heard throughout the interweaving of visuals, both found and created, in his newest work, The Image Book (Le livre d’image), as the master director quotes widely from George Orwell, Edward Said, Arthur Rimbaud, André Malraux, Charles Baudelaire, and Alexandre Dumas, but it is the line from playwright and poet, Bertolt Brecht, “Only the fragment conveys authenticity,” which Godard decisively gives us at the end of The Image Book that we can use to draw a surface to navigate through the construction of his film.

As with his work over the last few decades, The Image Book is a montage piece, editing together concepts and created with a narrative, or rather the creator’s personal thoughts, that appear selected by the current era. We must gaze upon this work as an installation piece, gathering the combination of sounds and visuals as a combined form in a single viewing and releasing any sense (and expectation) of traditional film language, as it has been Godard’s goal to further the language of film past any sense of where we feel entirely comfortable viewing it.

When experiencing Godard’s construction here, you see attempts to look at the ability of sound and image capturing and playback to actually freeze, perceive, and repeat reality, and without being pessimistic about the form, for this may be the director’s way of dismissing the medium, The Image Book’s primary concern is whether or not film is an appropriate conduit to capture reality. We understand that we experience what is real and recall what is real in desperate ways, and fundamentally, if cinema does the same, then it may be the closest way to show how we understand our world, even though that recollection, that attempt to recall the real may result in a falsehood. In utilizing some selections from modern cinema, most notably Gus Van Sant’s 2003 feature film revisioning of the Columbine shooting, Elephant, Godard articulates films’ tendencies to want to show true stories, which raises an existential question of whether or not the attempt to tell the story is always going to produce a work of fiction, and the same question applies for what we see in the news and what we are shown to believe is real, for the context of these snippets is designed by the channels that capture and replay them, and thus, we are presented these real moments in a manner that is completely separate from all of the images and sounds, all of the preceding and succeeding moments we would sense and experience if we were there.

Throughout The Image Book, we were constantly reminded of our favorite viewings from 2017 and 2018 respectively, Anocha Suwichakornpong’s By The Time It Gets Dark, and Gürcan Keltek’s Meteors, both films dealing with the way memory is processed and manipulated, not only by media, but also by time. These two films look at fiction interweaving with reality to get to the heart of human existence before and today, whereas Godard’s film is more about a need to document reality and the struggles to do so, both through fiction and non-fiction storytelling constructs. Godard’s film is more about filmmaking, but it is also about any other art form that we’ve participated in for centuries that attempts to frame and interpret real events.

At the center of The Image Book is Godard’s contention, through his selection of the fictional elements juxtaposed against documentary ones, that representation is flawed because the act of representation gives a shallow, distorted view of reality. Great thinkers and creators have had issues with this problem in their respective art forms: for example, author J.G. Ballard had problems with writing failing to be innovative, which likely came from the fact that writing is attempting to take reality and transform it into this representation that is antithetical to how reality is experienced. How do you describe so that you can fully sense at the same time? Sensory experiences can be ambiguous, so how do you then capture that ambiguity without writing something that is too opaque or oblique? That is the heart of the writer’s problem—this need to balance clarity, vagueness, and distance in description to evoke perception, then interpretation. However, with film, because its core elements, the image and the sound, are sensed, not read, which is closer to how we experience reality, that same writer’s balance has been diminished, and often purposely so, because we’ve desired a polished representation of reality, and we’ve liked what we’ve seen and heard because it is not as fragmented, not as confusing, not as challenging as the real. Godard knows our weaknesses in our expectations and standards for film, the manicured images and the sounds of films mistakenly luring us into believing the integrity of the representation of reality, and he wakes us up from our hallucinations in The Image Book.

With cinema, there are two things that have been overwhelmingly discussed for as long as the medium has existed, and that is love and violence. We then wonder if Godard’s closing call for revolution in The Image Book is also a plea for a new way to look at these concepts or to walk away from them completely. What are the purposes of the images of war here? That the West does not understand the Middle East? Perhaps, but, we think that there is more to his inclusion of these images than any particular geopolitical statement or condemnation. Simply put, the wars of the Middle East are the moist current violent conflicts in the popular mind, and if this film had been made some sixty years earlier with the same media capabilities that we have now, we most likely would be looking at the atrocities of the Algerian War, which Godard chose to handle with urgently-made narrative films like Le Petit Soldat and Les Carabiniers. The Image Book is about the relevance of the image, so we do see an entire section of the film dedicated to contemporary conflict, and older footage of previous conflicts does appear, but does not garner as much screen time, for Godard wants us to focus on the current incarnation of conflict, though not without an understanding of its past forms.

Fundamentally, the overwhelming success of The Image Book, as with most of Godard’s work throughout his career, comes primarily from the experiments attempted—successful or not as these experiments may be, they operate within the structure of the film to create a unique cinematic language. With his 47th feature, Godard, through the unique exploration and manipulation of old and new visuals and sound, has been able to duly note and thoughtfully deconstruct the core facets of cinema in order to find paths for its continued evolution as a vital device for interpreting reality.

◼

The Image Book is currently in limited release in the United States.