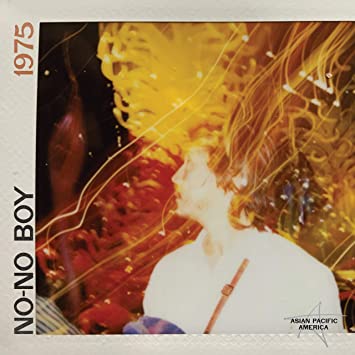

No-No Boy

1975

Smithsonian Folkways

It all started with a photograph of an all-Japanese jazz band in a Wyoming internment camp. The musician and historian, Julian Saporit, who records as No-No Boy, wanted to know the story of these imprisoned Americans who found a way to swing behind barbed wire. Julian’s curiosity eventually became his dissertation and the foundation of his academic career. Julian the musician wasn’t content to share the stories of Asians in America only in peer reviewed journals only read by other historians. As No-No Boy, he has distilled the essence of historical events into chords and verses.

The songs on 1975 are all based on historical events and real people. Julian weaves stories from his own family’s experience as refugees from Vietnam with stories of Japanese detainees, Chinese immigrants, Cambodian survivors and how their stories filter down the generations. The songs are a pentimento of overlapping memories. I feel like Julian is stirring up fragments of memory to excavate emotional truths. No-No Boy gives the chills.

“Imperial Twist” blends stories of his mother’s high school friend, Robert Vifian who played rock and roll in Saigon and a popular local group called the CBC Band. Robert’s story about learning songs from 45’s overlap with a CBC Band gig that got bombed as they started playing “Purple Haze.” Memories of “broken English Rolling Stones, Fenders, girls and dope” rub against tragedy. (The CBC Band finished that bombed out gig 40 years later when veterans who were at the show got survivors together in a Houston bar).

“Where the Sand Creek Meets the Arkansas River” meditates on overlapping tragedies and forgotten histories. The Amache concentration camp and the site of the 1864 Sand Creek Massacre both haunt southeast Colorado. The ghosts of the Arapahoe and Cheyenne who died at Sand Creek and those of Tonoki Ogata and the Mastuda baby are mostly forgotten.

The song “Khmerica” was brought to Julian by one of his students when he suggested she investigate her family’s Khmer history. The student’s father, Savoeoun, painted pictures of the Cambodia he remembered. The images Savoeoun painted showed temples bathed in sunsets and palm trees, not the things he saw living through the Khmer Rouge insanity.

“Some kids move because their parents take new jobs/ Some kids move ‘cause of napalm.”

Every song on 1975 is worth pondering. It’s worth listening and reading the back stories and lyrics. Let the sadness and perseverance wash through you. History is stories we tell each other. No-No Boy’s songs reveal stories of the Asian American experience are not always pleasant to recall but are important to know.

The song/story that won’t leave me along is “The Best God Damned Band in Wyoming.” I find hope hearing about the Japanese kids defiantly finding joy playing jazz for themselves, and getting a little time outside the barbed wire when they play gigs for the locals. I want to hear Joy Teraoka sing. I want to hear Little Tets Bessho wail on the clarinet and Yone play his trumpet. Julian puts so much life in these characters that I really want to hear more. I want Netflix to adapt this story for a movie or something.

I could write about the feels every one of these songs gives me. It’s not just the jazz kids from Heart Mountain that I want to get to know. I want to hear Julian’s bà ngoa tell stories about Vietnam before the war. I want to see those paintings of old Cambodia, Savoeoun painted. I want to go down to China Town and talk punk rock with Tony Ramone.