Andrey Zvyagintsev

by Generoso Fierro

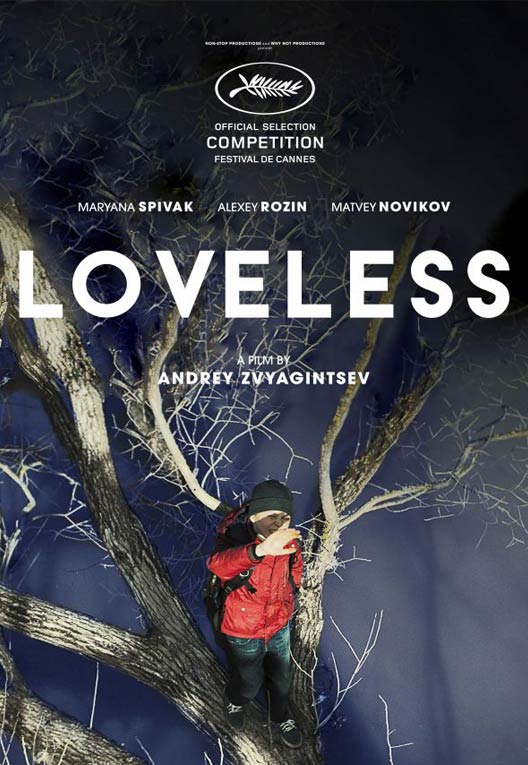

We were fortunate to have the opportunity to see twenty two feature films during this year AFI Fest held in Hollywood from November 9th to the 16th. Many were from veteran directors whose work we have appreciated over the years like Hong Sang-soo and Laurent Cantet, who gave us wonderful new features during the festival, but it was director Andrey Zvyagintsev, who we have admired since his 2003 film, Vozvrashchenie (The Return), who provided us with our favorite film of this year’s AFI Fest, Nelyubov (Loveless).

In Loveless, Zvyagintsev follows Zhenya (Maryana Spivak) and Boris (Aleksey Rozin), a soon to be divorced couple, whose constant battling has caused severe emotional trauma to their young son Alexey, who in the midst of his parents’ other ongoing dalliances, has gone missing, a fact which is not even noticed by his parents until days later. Loveless then becomes a film that plays with its audience by putting you in the position of the argumentative couple, who seem more concerned with their anger towards one another and seemingly unfulfilling affairs than the welfare of their own child. Throughout Loveless, we see youth as a commodity in contemporary Russia in terms of romantic pursuits, yet children are often seen as an encumbrance by adults for their attainment of more financial and status oriented goals. Another dichotomy that is also depicted in the film is the divide between religion and faith and how that plays out in the decisions of key characters, which became the focal point of my discussion with Andrey Zvyagintsev, along with a comment from Zvyagintsev’s longtime collaborator, producer Alexander Rodnyansky.

Q: In an early scene shot in a cafeteria that is adorned with religious paintings, we see Boris (Aleksey Rozin) speaking to a coworker about his boss, a character whom you never see, who has a requirement that all of his employees must be married. That scene drew my attention to how faith or religion is seen through certain key characters in your film. How does faith play a part in the narrative?

A: Zvyagintsev: So, the boss is not a completely fictional character. He is more of a composite of conservative ideals in Russia, but there is a person who we were thinking of specifically. There is a factory in Russia where the boss, Vasily Boiko, had 6,500 employees under him, and in 2010, he told all of his employees who were spouses to get married in a religious ceremony or else they would be dismissed. In terms of religion, for a true believer, there is a clear distinction like the one between an ostrich and an eagle, a clear difference between good and bad, and that line goes through that person’s heart. And for those who are not true believers like the boss, that line is between them and the world, so they truly believe in their own Pagan ideas, conservative views like the ones displayed by this character. So, in my film this character is quite satirical. Oh, and one more thing, Vasily Boiko has added “the great” to his title so now he is Boiko The Great. (laughter)

A: Rodnyansky: It was really important for us that the comments that we are making are not about faith, but about the religion. We want to make it clear that we are speaking about the church as an institution, and let’s say the intrusion of the church into secular life as an organization, so our film does not make any comment about faith. Of course, we have a lot of true believers, perhaps not as much as we used to have one hundred years ago, but we still do have a lot. When people speak about the church, we can see it is playing a role in what the people perceive as faith. The church is a kind of an administrative department of the contemporary government. That is why we believe that this is an extraordinarily effective tool to implement the so-called conservative values in Russia today. That is why when we speak about the “religious” people, we always have a distinction between the true believers and the ones involved with the institution.

Q: You show youth as a definitive commodity in contemporary Russian culture as seen through the extramarital affairs of Zhenya and Boris. I was impressed in the film by the intense level of the search that the private/non-governmental organization mounts when Alexey goes missing. Is that level of intense search more a function of the value of youth in Russian society, or more due to Boris and Zhenya’s affluent economic status?

A: Zvyagintsev: Because this is a volunteer organization that has existed for seven years called Liza Alert, the people involved work regular jobs and do the searches for missing people for free. This organization looks for all missing people, so it does not have to be a child who is missing. When they receive a request, there is no money that changes hands, so the economic status of Boris and Zheyna does not play a role here. It could of course be the parents of a lost child that the organization has been asked to help, but it could also be a wife looking for her spouse, or children looking for their parents, so age does not matter, financial status does not matter. It is the awakening of citizens and their ability to organize themselves, and they do this only because of their empathy and desire to help in a way that the government cannot.

Q: Have organizations like Liza Alert become more prevalent recently because of a specific crisis, like the refugee crisis in Syria or the conflict in the Ukraine?

A: Zvyagintsev: No, not specifically the Ukraine or Syria, it is just a need that had to be addressed by citizens in a way that the Russian government was unable to do.

Q: I ask this question as you regularly show dire, almost apocalyptic political situations in Russia via news clips seen on television during your film. This brings me back to my initial thoughts on how religion and faith are exhibited by the characters and how there may be a divide between older Russians who are gravitating towards religion because of the state of their country, and younger people who have become more secular because of the failings of the previous generation. Organized religion as you stated earlier is being used to foster conservative ideals. In general, is the current political situation driving more Russians closer or farther from organized faith, away or towards being “true believers’ as you say?

A:Zvyagintsev: Statistics show that 74% of Russians say that they are believers, but when they asked that 74% if they had read the Bible or the central text of their faith, only 30% admit that they have actually read the text. It is essentially like Paganism in that there is a social sickness, and a lot of people who consider themselves “believers” don’t understand which god they serve. So, questions about growth of numbers really don’t reflect what is going on in society. It is a social sickness of Paganism rather than true belief. This sickness isn’t just unique to Russia, it is going on all over the world. There are a lot of people who look for God, but find a short God. So, the criteria for a person who is a true believer, a true Christian, like I mentioned earlier, is that he has his border between good and evil going through his heart. It is an epic battle between your real self and your fake self, and if the person sees that evil is not within him, like this religious person who considers the line between good and evil to be outside of him, then he is a fake and not a true believer.

Loveless open in New York and Los Angeles on February 16. 2018