A Musical Manifesto for the Pandemic

by Jeffrey Schweers

No other album has helped me endure the strain of the coronavirus pandemic more than Robyn Hitchcock’s Globe of Frogs. The 1988 album, his third with backup band the Egyptians, featuring the impeccable Andy Metcalfe on bass and Morris Windsor on drums, skitters from one absurdist, sometimes apocalyptic, sometimes sexual scenario to another, shifting musical gears throughout its delightful 36 minutes and change.

For one thing, I can’t think of a single pop or rock record out there that comes with a manifesto that explains exactly what the artists are trying to achieve, and adds in a healthy dollop or two of healthy sexual perversity as only the British can.

“This album does not deal with the conventional problems of so-called ‘real’ life; relationships, injustice, politics, and central heating systems, about which it’s notoriously hard to talk because orthodox lines of cliché have been devised for and against everything,” says Hitchcock, modern rock’s Oscar Wilde.

He dismisses the glib, hackneyed slogans pop music can descend into and how the music business serves to please and distract. He’s just as dismissive of politics and advises us to bury our television sets.

“I’m concentrating instead on the organic. All of us exist in a swarming, pulsating world, driven mostly by an unconscious that we ignore and misunderstand. Within the framework of ‘civilization’ we remain as savage as possible,” he says.

It’s the “dense traffic of modern life” we are shielding ourselves from with violent videos , virtual sex and music. Always music.

So, Globe of Frogs offers an alchemic alternative to the technopocalypse, an organic world ruled by the natural laws not created by humankind. Random, violent, sensuous, chaotic, beautiful.

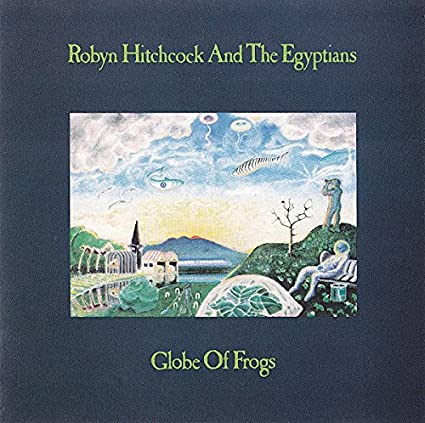

The album cover, an original painting by Hitchcock, offers a glimpse of what that world might look like. Striped zebra fish, silver fish and jelly fish swim in the sky as a green-bandaged, vegetable-looking humanoid stands on a knoll and observes through a set of binoculars. A dead, leafless tree is nearby.

What appears to be a person in a spacesuit rests on a park bench on the same knoll. A closer look reveals a skull inside the glass orb helmet of the space suit. What appear to be dead fish litter the hillside.

Another humanoid creature holding what appears to be a scythe is doing something in the valley below. Fish float in and out of strange buildings on a jetty near a lake. The sun sets behind distant mountains.

You wonder what dangerous world this is taken over by nature as you play the first song, “Tropical Flesh Mandala,” a giddy, upbeat little number about scary things emerging from the murky waters onto a beach.

Although the sight of this pink-scaled, tiny-feathered thing with many valves opening and closing gives the narrator an irrational sense of pleasure, he ominously sings, “Underneath your ribcage and your skin, Honey, there’s a new way to get in.”

The song gallops along into an avant-garde piano solo before coming back to the basic groove, ending with a creepy punchline: “On the night the creatures came to shore, someone told Joanna what they’re for.”

That segues into “Vibrating.” With a crashing drum and throbbing bass line it sets up a thrumming, dynamic drone as the narrator tells the tale of a woman who buys a pug and can’t stop vibrating. Is she the same woman from the previous song?

The dog dies, his bones form an alphabet on the grass, beautiful and obscene, and fleshy flowers in a demon’s mesmerize the damsel as she vibrates into oblivion.

The bouncy “Balloon man” was supposedly written for The Bangles. But try as I might, I cannot imagine Susannah Hoffs singing about spherical heads spewing hummus and chunks of tomatoes all over the place and jumping off the Empire State Building filled with marshmallows. Delightfully bonkers, the song continues to mine the recurring theme of gross organic matter and insanity.

From the Manifesto: “But our inflamed and disoriented psyches smolder on beneath the wet leaves of habit. Insanity is big business.”

Propelled by Metcalfe’s accordion, which sounds like a harmonium here, the purposefully quieter “Luminous Rose” follows, a spare meditation on receiving the news of the death of someone you love. The ocean – deeper than the grave – is portrayed as a living breathing entity, taking the dead sailors into her arms as fish nibble on their fingers, flesh giving way to coral.

It is one of the more introspective of Hitchcock’s songs, and has the great line “God finds you naked and he leaves you dying. What happens in between is up to you.”

Robyn and the band kick it back into high gear with the raucous rockabilly number, “Sleeping With Your Devil Mask.” The innocent-sounding nursery-rhymey opening verses of birdies in trees and fishes in seas soon gives way to a menacing man perched upon the garden wall who “made it all.”

The narrator sings, “I see right through into your bones Your skeleton can dance all night And caper ‘neath the swaying light” before launching into the chorus.

Then, in the same verse, he name drops Dennis Forbes, a montagist, illustrator and Egyptologist who was the art director for The Advocate in San Francisco in the 1970s, and a sultry Gareth Hobbes, who has a bunch of useless jobs and is a fictional American serial killer from the Hannibal Lecter book and movie, Red Dragon.

After the narrator intones, “It’s all compulsion, there is no choice,” he describes a scene where his mother (whose name is JOYCE) witnessed the execution of a cellist. A Bunuel-like coven of 13 “men with long black heads” stand around her bed until their heads caved in and their rotting brains fell to the floor and crawled away. Nice.

The final verse deals with an organism that rapes itself and gives birth upon a shelf, which seems like a call back to the action in Tropical Flesh Mandala. Meanwhile, the narrator grows a flower in his gut and tells us in our next life we will return to this earth as a trout.

The absurdity continues with “Unsettled,” as Hitchcock strings together words and syllables with the zest of James Joyce during Finnegan’s Wake that sound good and rhythmic but mean very little and yet sound vaguely ominous and threatening: swallow piston in you shatter, blood or glass eruption, seen druids, forest fire, dogs expire.

The words come at a Dylanlesque pace until suddenly he announces “Casserole is friendship.”

Next thing you know, a Lennon-like word salad of potatoes and lasagna and tomatoes and moussaka are tossed around until, biting off a crust, the narrator says, “What can I say to you?”

Unsettled, indeed. Even the music threatens to go off kilter any second.

This maelstrom is followed by the most beautiful “Chinese Bones.” Ethereal and floating along chiming guitars a la Peter Buck of REM, the narrator contemplates Romeo, Juliet, snakes and dwarves, mirrors and lakes and statues that might have stared at their reflection too long.

One thing Shakespeare never said was, “Man, you’ve got to be kidding.”

The title track rides on a spare rhythm built on an Indian drum played by Windsor, then builds up with guitar, harmonica and other instruments kicking in and fading out as funny goings on are described in a greenhouse? Arboretum? Terrarium?

A woman, maybe the same woman emotionally scarred by the creatures of “Tropical Flesh Mandala” is feeding happy, hungry flowers, walking across oozing floorboards and listening to a creaky house full of disembodied souls, and fish that like to nibble on her thumbs, and a mouth unravels as a flower breathing for the word: a soul.

The next song, “The Shapes Between Us Turn Into Animals,” is a hard-rocking and ominous distorted guitar alarm bell warning us of the coming dread. It’s as if the ideas an themes of all the previous songs come to a head here. We are back in the realm of science, muck and algebra, a woman with hair like anemones, under the sea, waving her fingers.

More nonsense about lions and zebras and baboons, a nighttime thrill ride through the house of love till morning comes. Everything is smashed into bits.

And after all that violent thrashing about, a moment of silence before the final song, “Flesh Number One (Beatle Dennis)”, It’s a most infectious, sweet ditty propelled by Buck’s jangly 12-string guitar as Robyn and Glenn Tilbrook sing about house fires, plane crashes and erectile dysfunction so far removed from two lovers that they don’t seem to mind. They’re not there, they’re in love and they’re as far as I can tell… and the song concludes with the refrain, “There’s nothing happening to you that means anything at all.”

And that is as good a mantra as I can come up with to help me get through the pandemic, however long that may be.

If it all ended right then and there, it would be a satisfying album, but the way the album is arranged, “Flesh Number One” easily segues right back into “Tropical Flesh Mandala”, creating a melodic Moebius strip of sound I can listen to over and over again, as long as this crisis lasts.

Because, after all, as Robyn says in the manifesto:

“My contention is, however – and it’s a bloody obvious one – that beneath our civilized glazing, we are all deviants, all alone, and all peculiar. This flies in the face of mass marketing, but I’m sticking with it.” ◼